By STEPHEN FIDLER, GABRIELE STEINHAUSER and MARCUS WALKER

BRUSSELS—The deal hammered out by euro-zone leaders at a summit in the early hours Friday, which forced Germany into concessions it had so far resisted, powered financial markets higher on tentative hopes that the euro-zone's debt and banking crises could be reaching an inflection point.

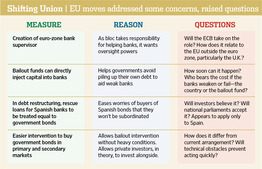

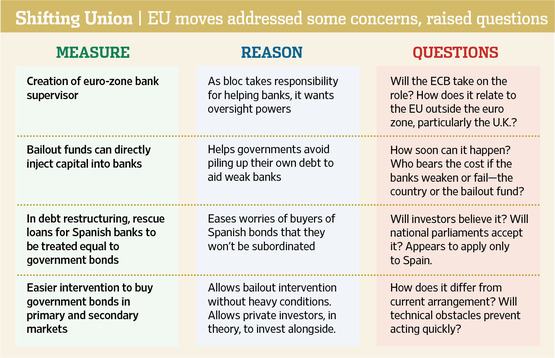

Leaders in Brussels took a significant step toward closer integration of the currency bloc, deciding that a single supervisor should oversee banks in the 17 nations that use the currency. Details of the role, likely to be handed to the European Central Bank in Frankfurt, will be mapped out by the year's end.

The leaders also agreed to some nearer-term measures designed to help Spain and Italy, whose rising borrowing costs have heightened the sense of crisis around the survival of the single currency.

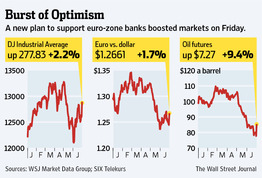

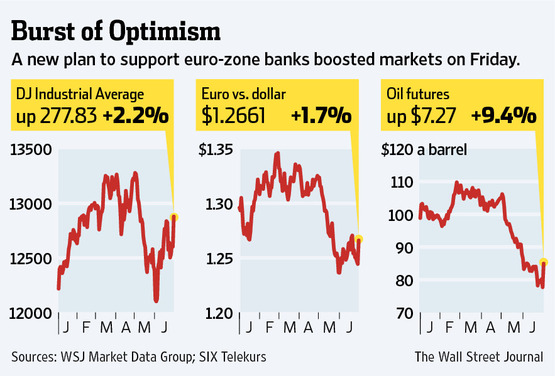

Yields on bonds of Spain and Italy—whose high borrowing costs have been an urgent concern—fell markedly. European stock markets and the euro rallied, and optimism spread to international markets. The Dow Jones Industrial Average jumped 277.83 points, or 2.20%, to 12880.09, and the broader Standard & Poor's 500-stock index logged its best day of the year, rising 2.50%. Beaten-down commodities prices also jumped. Crude oil, which is tied to expectations for global growth and consumer demand, soared 9.4%, its biggest one-day rise since March 2009.

In the past, however, investors have picked apart summit conclusions that they had initially applauded. Some of Friday's measures were short on details, which will have to be hammered out by a finance ministers meeting on July 9.

Streaming Coverage

Follow every article, blog post, video and tweet on the debt crisis from our reporters across Europe.

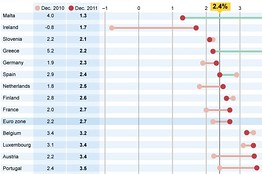

Euro Zone by the Numbers

The 17-nation euro zone is a collection of countries with vastly different economic profiles. See how they stack up on the major measures.

Still, the agreements reflect the growing strength of the forces arrayed against German Chancellor Angela Merkel, the key actor in most euro-zone summits. Leading the challenge was Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti, who is trying to stave off a financial crisis threatening his own country.

In an effort to secure concessions, Mr. Monti threatened to keep leaders in Brussels until they had agreed to measures to help Spain and Italy, officials said. The move would have held up accord on a "growth pact" that Ms. Merkel had promised politicians at home.

As Mr. Monti cajoled his counterparts, several officials said he held out the prospect that if he wasn't granted concessions, Italian elections might well bring his predecessor back to power. Silvio Berlusconi's government is blamed by many leaders for precipitating Italy's predicament, and the former prime minister had a long, nettlesome history on the European stage and with Ms. Merkel in particular.

Mr. Berlusconi's People of Freedom Party and other political groups that back Mr. Monti in Parliament had been warning for weeks that Mr. Monti's job was on the line if he didn't return from the summit with concrete results.A spokeswoman for Mr. Monti said the premier didn't mention Mr. Berlusconi at the summit.

The summit dynamic had changed since Nicolas Sarkozy lost his bid in May to recapture the French presidency, said one senior official. Mr. Sarkozy's pre-summit consultations with Ms. Merkel ensured many proposals opposed by Berlin were kept off the table.

"The south is now more assertive" at summits, the official said, adding that Mr. Monti was also backed by Mariano Rajoy, the new Spanish prime minister.

During discussions between the 17 euro leaders, which officials described as "passionate" and "tough," Ms. Merkel said she and Mr. Monti stepped to the side "at least 10 times" throughout the night to nail down the wording of the final statement. Mr. Monti said afterward that in the past, European leaders have "treated each other with excessive gentleness."

Mr. Monti's pressure helped secure three agreements. First, Germany agreed to allow the bloc's bailout funds to directly inject capital into struggling banks, a step that should help Spain. It also agreed that aid for Spanish banks wouldn't outrank the claims of regular government bondholders in the event of any debt restructuring, and to a move that leaders said would make it simpler for European bailout funds to intervene in the bond markets of Spain and Italy.

These represented concessions from Ms. Merkel that were more significant than at any previous summit since the debt crisis began in late 2009. For weeks, Ms. Merkel has insisted that the bailout funds would only ever be allowed to lend to euro-zone governments, not inject capital into banks.

She had long said that loans from the European Stability Mechanism, the new euro-zone bailout fund that should come into operation later this summer, must be repaid in full even if a government's bonds are restructured. She had also maintained that the ESM could buy a country's bonds only as part of a tough program of fiscal and economic overhauls.

Ms. Merkel dropped or greatly softened all three of those positions in the small hours of Friday morning. In return, she won agreement to create the new euro-wide bank supervisor.

Ms. Merkel played down her concessions at a news conference in Brussels, saying that details remained to be settled, giving Germany plenty of time and opportunity to ensure it wouldn't hand over its taxpayers' money without adequate controls.

She also stressed that Germany's parliament would have to approve the new financial-aid tools, as well as any actual use of them. Direct aid for banks will be possible only after the euro zone has a central banking supervisor that Germany trusts, she said.

But German media and lawmakers saw them as concessions, and many reacted angrily. "Merkel gives in—Italy and Spain win at the EU summit," said the website of Germany's mass-circulation tabloid newspaper Bild.

The reactions showed the difficulty of Ms. Merkel's balancing act. She knows saving the euro will require costly and risky steps by Germany. She also fears the potential for political backlash against bailout measures among voters and lawmakers.

Her agreement to make ESM loans to Spain equal to Spanish bonds in creditors' pecking order was largely a recognition by Germany that this was necessary to protect Spain's ability to sell bonds, German officials say. Many bond investors have warned that making Spanish ESM debt senior to Spanish bond debt was a mistake, since it increased the risk of losses on the bonds, and Berlin has accepted that this was one reason why the €100 billion ($125 billion) aid package requested for Spain's banks on Monday had failed to reassure financial markets.

Germany appears to have made its other two concessions through gritted teeth, however. By next year, German taxpayers could, via the bailout funds, become indirect investors in risky Spanish banks—and lenders to an Italian government that won't be subject to particularly arduous policy conditions or to monitoring by the International Monetary Fund.

German officials say Ms. Merkel was eager to help Mr. Monti with the latter concession. Mr. Monti badly needed a political victory at home, as well as help in curbing the rise of Italian bond yields, these officials say. Although Mr. Monti hasn't fulfilled all of Ms. Merkel's hopes that he reform Italy's economy, Berlin is worried that whoever follows the Italian premier might be much less reform-minded.

Officials said a lot of details remained to be settled. For example, they didn't specify whether countries benefiting from direct bank recapitalizations would have to retain final liability for any losses and how the bailout fund would deal with any stakes in banks it could end up with.

"The negotiations will once again be tough," Ms. Merkel said. "And they certainly won't take just 10 days."

—Jonathan Cheng and Alessandra Galloni contributed to this article.Write to Stephen Fidler at stephen.fidler@wsj.com and Marcus Walker at marcus.walker@wsj.com

A version of this article appeared June 30, 2012, on page A1 in the U.S. edition of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: Investors Cheer Europe Deal.

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-TD325_eurost_D_20120529052151.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MK-BV397_SOCCER_A_20120701185645.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/AI-BT880_AUSIND_A_20120701142840.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/AI-BT878_JNUKE_A_20120701175727.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-BG850_SCYTHE_C_20120629173254.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-TO602_boxila_C_20120628203443.jpg)

![[OB-TO555_spidey_C_20120628175021.jpg]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-TO555_spidey_C_20120628175021.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OD-AS358_CRUISE_C_20120628134552.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/RV-AH340_MASTER_C_20120628162030.jpg)

Most Recommended

“Try and fathom the hypocrisy of ...;”

“Perhaps, Mr Gensert, it's not th...;”

“Another thoughtful and concise...;”

“However, Ms Napolitano immediate...;”

“My thought, exactly...You go on...;”