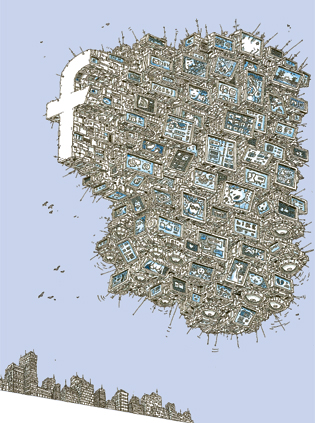

Can Anything Take Down the Facebook Juggernaut?

- 05.16.12 12:59 PM

Illustration: Mister Mourao

Sometime in early 2004, as Mark Zuckerberg was furiously coding the first iterations of The Facebook in his Harvard dorm room, the Internet passed what then seemed to be an impressive milestone: 750 million people worldwide had become connected. The exact birthdate of the Internet is difficult to pin down, but it’s fair to say that it took at least three decades for the net to reach a population of that size.

Today, after just eight years in existence, Facebook now has more than 750 million users all by itself. At that astonishing rate of growth, the company is on track to accomplish much more than just a multibillion-dollar IPO. Facebook is on the cusp of becoming a medium unto itself—more akin to television as a whole than a single network, and more like the entire web than just one online destination. The evidence for that transformation goes well beyond the sheer number of users. Many businesses now bypass the traditional web altogether, limiting their online presence to Facebook. Already the platform has spawned one billion-dollar company (the social gaming giant Zynga) and swallowed another (the photo network Instagram). The average time people spend on the site has increased from four and a half hours per month in 2009 to nearly seven hours—more than twice that of any major web competitor.

Also in this issue

Facebook’s growing dominance suggests that the platform may very well represent the third major evolution of the network age. First the Internet popularized the crucial organizing principles of peer-to-peer architecture and packet-switched data. Then the web ushered in a new set of governing metaphors that were fundamentally literary in nature: a network of “pages” and footnote-like links. Powerful as they were, though, both those platforms were organized around data, not people. From a computer scientist’s perspective, this might not have seemed like a shortcoming. But most human beings don’t naturally organize the world through metaphors of domains or hypertext; instead they mentally map the world according to their social networks of friends, family, and colleagues.

So it should come as no surprise that we now find ourselves gravitating toward a new platform grounded in those social maps. And the bigger we make the platform, the stronger its gravitational pull. The Internet—meaning everything from email to file trading to voice-over-IP phone calls—was always technically larger than the web, but the web’s mass adoption managed somehow to overwhelm the vessel that contained it. The web became the main attraction; the packets and DNS lookups became the plumbing, essential but invisible. Facebook now threatens to perform that same jujitsu against the web itself. The difference, of course, is that no one owns the web—or in some strange way we all own it. But with Facebook we are ultimately just tenant farmers on the land; we make it more productive with our labor, but the ground belongs to someone else.

The sheer magnitude of Facebook’s success is one reason why, as the company charges toward what will likely be the most successful public offering in the history of capitalism, its critics are growing in number. Troublesome corporate behavior is easier to swallow when there are other choices out there, when you have the option to take your business to another store down the street. But when one company owns the whole street, each little transgression is amplified. A few years ago, the primary critique of Facebook revolved around its prodigious capacity for wasting our time. Today the complaints run much deeper: Facebook, we’re told, is a threat to core social values, to privacy, to the web itself.

The most vociferous of Facebook’s detractors contend that it has a long track record of aggressive, if not downright abusive, privacy policies. An early attempt at personalized advertising, Beacon, was famously aborted after users filed a class-action suit claiming that their personal activities online (including purchases made from various ecommerce sites) had been revealed to advertisers and friends without their knowledge. The company’s new Open Graph protocol gives developers the ability to share user behavior in one Facebook app—third-party programs that, like Zynga, run inside Facebook—with other apps that might want the data. For example, if you announce in a recipe app that you’ve cooked a particular dish for dinner, that news can be broadcast to your feed or put to use by a dieting app that tracks how many calories you’ve consumed.

No doubt Open Graph will lead to some wonderfully inventive and useful new tools, not to mention a vast universe of mindless social entertainment. The problem is that most of us don’t have time to monitor all the various ways our actions are going to be shared and tracked across the network. Launch an Open Graph app using your Facebook ID and you’ll get a warning that says something along these lines: “This application may: post status messages, notes, photos, and videos on my behalf; access my data at any time; access my data when I’m not using the application.” Technically, this language is simply describing the consequences of a “seamless sharing” world (in Facebook’s preferred phrase). But as a practical matter, do users know what they’re signing up for?

To Facebook’s credit, the company has given people very granular control over their privacy—the privacy settings page includes dozens of separate options that can be toggled on or off. And it has a long track record of success in putting users at ease, eventually, with new features; initial criticism usually softens into acceptance and, soon, enthusiasm. It’s easy to forget that even the News Feed feature, which now seems unobjectionable (and indispensable), sparked a backlash when it was launched. When the company makes mistakes, it seems to learn from them: Beacon was pulled, and recent updates have greatly simplified the privacy-settings page so users don’t get overwhelmed with the initial dashboard of options.