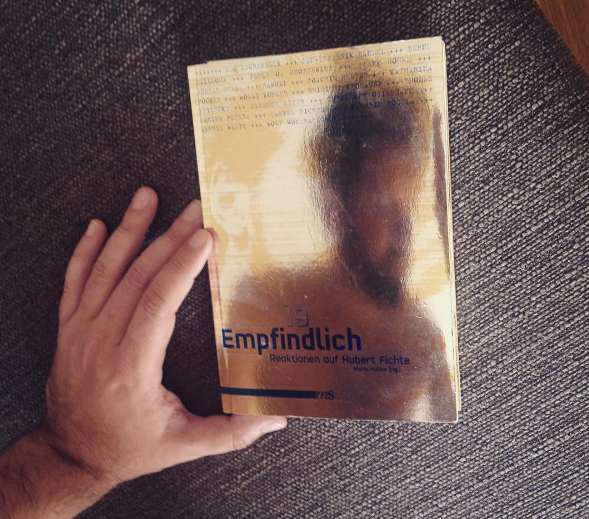

Foto: Marc Lippuner – Book: Männerschwarm Verlag, 2010

.

For three days in July 2016, the „Empfindlichkeiten“ literature festival/conference at the Literarisches Colloquium Berlin invited nearly 40 international writers, scholars, artists and experts to disquss the aesthetics, challenges, politics of and differences within queer literature.

Before the conference, all guests wrote short statements – translated into English by Bradley Smith, Simon Knight, Oya Akin, Lawrence Schimel, David LeGuillermic, Pamela Selwyn, Zaia Alexander and Bill Martin.

I read these statements – a digital file of 67 pages – and compiled my favorite quotes.

It’s a personal selection, and all quotes are part of much larger contexts.

Still: to me, this is the – interesting! – tip of a – super-interesting! – iceberg:

queer literary discourse, 2016.

.

.

I am certain that my writing would be completely different without my being gay. As a queer young person, you grow up with the awareness of living in a society that isn’t made for you. This influenced a particular perspective that expanded to all aspects. Things that are very important for many people don’t affect me much – but I am very touched by other things for which most people are not sensitive. – Kristof Magnusson

Just at the beginning of my career as a writer, in 1996, I was a guest at the national radio show for young writers. The editor asked me whether I planned to write a novel. He thought I couldn’t really accomplish it because my shovel wasn’t big enough. What he meant was that as »a real writer« one would need a shovel big enough to grasp all the worldly experiences, memories, histries, feelings, etc. not just the minor ones. And being a lesbian, my experiences are rather minor, particular and only autobiographical, and therefore cannot really address the big world out there.

I spent a lot of time writing and fighting against this prejudice that straight writers – being mainly »just writers« without labels – write about the world, but gay, lesbian or queer writers write only or mostly about themselves and their lives, even more, they simply write from within themselves. – Suzana Tratnik

.

.

To call a prick a prick is an act of self-assertion as a free man. – Joachim Helfer

To bashfully shroud it does nothing to make the vile pure, but may make the pure appear vile. De Sade is the ancestor of a more modern gay style of provocative divestiture. Jean Genet, Hubert Fichte and others (including myself) work from the assumption that even – or especially! – the most indecent exposure of man’s physical existence can but reveal his metaphysical truth: the untouchable dignity of each and every human being. It is this pure belief that permeates contemporary popular gay culture, from Tom of Finland and Ralf König to the anonymous participants in any Gay Pride Parade. – Joachim Helfer

‘Empfindlichkeiten’ – the motto of our conference hurts. In German, this is a charmingly provocative neologism in the association-rich plural form. Yes, we ARE sensitive. We lesbians, gay men and other kindred of the polymorphously perverse. Not just sensitive like artists are said to be, but over-sensitive in the pejorative sense. And we have every reason to be. Not just in all those countries in Eastern Europe or Africa where people like us are once again being, or have always been, marginalized, beaten, raped and murdered. The massacre in a gay bar in Orlando, Florida on 12 June 2016 is sad evidence that homophobic violence remains an everyday occurrence in liberal western countries too. In places like Germany, where it lies dormant alongside gay marriage, it can all too easily be reawakened (AfD, Pegida, Legida). – Angela Steidele

.

.

In Greenland there is no such thing as a literary environment and therefore no literary debates, not to mention literary debates about homosexuality. Of course books in Greenlandic are published every year, but extremely few have an influence on public debates. There are no festivals, no readings, nor reviews on the local medias. That, in general, causes no development among the few Greenlandic writers. Greenlandic books exist only as decorations – students read them in school, only because it’s mandatory. Very few buy them for private use, and when they do, they finish reading them only to hide them in a shelf to collect dust – Niviaq Korneliussen

When my book, HOMO sapienne, was published, people started to use it for debates; politicians used my phrases, scientist used my criticism of the society, homosexuals cherished probably the very first book about not heterosexual people, and readers discussed the context. Schools invited me to talk about my book and I’ve been participating in many cultural events. The reason for that, I think, is because my book is contemporary and relevant and criticizes people who aren’t used to being criticized. Although my book is being discussed a lot, people in Greenland don’t seem to talk about the fact that there are no straight people in it. I don’t consider my book as being queerliteratur, but you can’t bypass that the characters are queer. – Niviaq Korneliussen

[In Spain,] the Franco Regime continued a long tradition of homophobia on the Iberian Peninsula which once had been, at the end of the Middle Ages, long before the so-called Reconquista, a multicultural society where Arabs, Jews and Christians had coexisted quite peacefully. Among the prejudices towards the ‘Moors’ the Christian Emperors liked to highlight their supposed homosexuality, a feature they later transferred to the Native Americans after the terrible Conquista of South America. The prototypical Other was gay, and vice versa… – Dieter Ingenschay

Some critics find a decline in the production of literature with homosexual subjects after 2007, annus mirabilis which brought two important elements of social change: the above-mentioned Law of Equal Rights and the Law of Historic Memory (Ley de Memoria histórica) which was supposed to help working through the crimes of Franco’s dictatorship. These achievements, as some critics say, produced a decriminalization and hence a ‘normalization’ of the life of gays and lesbians. This is partly true, no doubt, but both laws have not yet really translated into social life. Franco’s followers still have great influence, and conservativism, machismo and the secret influence of the Catholic Church (with their disastrous organizations like the Opus Dei) still force thousands of young people to hide their (sexual) identity, especially in the rural parts of the country, – Dieter Ingenschay

.

.

The paradox that all those who are oppressed sometimes feel: the belief that their oppression offers them an extraordinary tool for personal growth and creativity. In Spain, during the 1980s, it became fashionable to cynically state that „we lived better fighting against Franco“ and to insist that censorship forced the great writers to hone their intelligence and imagination. The question could now be reformulated in this way: would gay literature disappear in a hypothetical egalitarian world? Would there cease to be a specifically homosexual creativity when not just legal discrimination, but also social homophobia, disappeared? I don’t think that any reasonable human being would lament that loss, in the case of its ever occurring. – Luisge Martín

Unrequited love. It is a mathematical issue: the homosexual will always be in a minority, will always love he who cannot love him in return. – Luisge Martín

Since the French Revolution at the latest, the entire concept of so-called femininity a genuine masculine, phallological construction, with philosophers, educators, gynaecologists and couturiers responsible for its stability. I consider it more interesting how this construction has more recently been turned inside out in many contexts and also how the artificiality of traditionally highly defined masculinity has been performatively emphasized by women. – Thomas Meinecke

.

.

[…] sexual and romantic relationships between women have been close to invisible. They are largely absent from both the historical record and the literary canon. This absence damages our sense of ourselves, our sexuality and our place in the world. It is as if our lives have been outside the range of human experience until the last fifty or sixty years. We need a lesbian history. But finding it is a bit like searching for buried treasure without a map. There are, however, clues; hints of the past left in diaries, letters and newspaper reports. Novelists are using these glimpses of our lesbian/queer ancestors to rescue the hidden history of relationships between women. For literary historian and novelist Emma Donoghue, writers are “digging up – or rather, creating – a history for lesbians.” – Hilary McCollum

[In Turkey,] there is a predominant attitude along the lines of “Kill me if you like, but DON’T admit that you’re gay.” It’s for this reason that lots of homosexuals get married, and to save face they even have children. […] In other words, homosexuality is still an “issue” which needs to greatly be kept secret, suppressed within the Turkish society. It is a state of faultiness/defectiveness, guilt and an absolute tool of otherization. Especially in Anatolia. I wrote “Ali and Ramazan” to come out against this entire heavily hypocritical, oppressive attitude. – Perihan Mağden

.

.

In Canada, where same-sex marriage was legalized in 2005, it can often seem on the surface to be a utopia of acceptance. But as the outrage and protest against my debut Young Adult novel When Everything Feels like the Movies revealed, it’s okay to be gay — as long as being gay means being like everyone else. There was a backlash against the perceived vulgarity and explicitness of the language represented in my novel — language which was often ripped directly from the mouths of the gay youth who composed my inner circle of friends and acquaintances. It appears that in achieving equality in the civilized world, gay culture is being sacrificed. Unity and equality should not have to mean homogenization. The traditions of gay culture for better and worse — the underground camp, irreverence, and brash sexuality cumulative of decades of having been ostracized by mainstream society — is no longer relevant or understood in our modern, equal times. It is therefore the responsibility of LGBT writers to document and immortalize our traditions as our culture shifts so that we don’t lose what makes us unique in order to gain acceptance. Marketing our stories to young readers is paramount to this effort. – Raziel Reid

To be an object of hate speech, to witness floods of hate speech exuded daily by politicians, newspersons, sport coaches, university professors, and clergymen resembles a bad dream. When reading Kafka at thirteen, I experienced a suffocating feeling of immense revulsion and pity. Why was this happening to Gregor? The story didn’t say. But it communicated clearly how vulnerable life becomes as soon as one is transformed into an object of disgust to others. – Izabela Morska

The gay life in Istanbul, as is the case with many others, changed dimension after the occurrences of the GeziPark protests, we can safely say that it has adopted a more organized and daring attitude. The Gay Pride which took place in the summer of 2013, during the GeziPark, was tremendously effusive, and was supported and claimed not only by the gay community, but the heterosexual community also. This great power most probably disturbed the present Turkish administration, for the Gay Pride which took place the following year was met with police raids, and the groups were attacked with gas bombs and the parade suffered a drastic blow. – Ahmet Sami Özbudak

For in an Islamic country, living a free and open homosexual life is unacceptable. If the prevalent Islamic atmosphere increases its intensity and Turkey becomes an even more fanatic Islamic country, the fight for existence for the gay community will become even more difficult. – Ahmet Sami Özbudak

.

.

I am so glad to see that there are several young queer rappers and djs who can rely on and collaborate with a scene and multiple protagonists who are much like them. These people like me refuse to use discriminatory, hateful language. They empower themselves by combining the personal with the political and build a language that makes them unique as rappers and outspoken as queer fighters, lovers and dreamers. The rap mainstream has slowly come to the point that we can’t be ignored anymore. There is still separation, but no more negation. – Sookee

I have come to the straightforward conclusion that the homosexuality of the author is not necessarily reflected in the content of his or her work, but rather in the way in which he or she looks out on the world. I am thinking, for example, of writers such as Henry James, E.M. Forster or William Somerset Maugham: in their novels and short stories, you hardly ever come across homosexual content, but it is impossible not to sense their homosexual identity. – Mario Fortunato

The notion of a ‘gay literature’ is a product of precisely these discourses of power. It was invented to cement the idea that real literature is straight. In this scenario, gay literature is a niche product that only those directly affected need to bother about. – Robert Gillett

.

.

For some 200 years, a particular variant of violence against lesbians was the assertion that we didn’t exist. Until the mid-eighteenth century, sex between women carried a death penalty just as it did between men. It was in the Enlightenment, oddly enough, that male philosophers, jurists and theorists of femininity became persuaded that sex between women could be nothing more than preposterous ‘indecent trifling’. Trapped in their phallocentric worldview, they abolished the penalties for lesbian sex beginning around 1800, because in their opinion there was no such thing (the English and French penal codes had never even mentioned it in the first place). Women-loving women disappeared into non-existence, reappearing in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century novels as ghosts and vampires at best, in any case as imaginary beings. […] My work is dedicated to giving the women-loving women of (early) modern Europe back their voices and making their stories known. – Angela Steidele

We have lived through times in which heterosexuals went to great lengths, partially with violence, to separate themselves from homosexuals. As a result, homosexuals began to separate themselves from heterosexuals, a liberation movement that aspired to a life as a supplement to the majority. – Gunther Geltinger

Writing in a homosexual way means not only acknowledging my origin, education, and traditions, but also permanently questioning them. – Gunther Geltinger

.

.

From the word ‘liwat/looti’ (used to refer to male homosexuals and which suggests the act of sodomy), to the female ‘sihaqah’ (which can be roughly translated to ‘grinder’), as well as the word ‘khanith/mukhannath’ (popular in the Gulf and drawing on memories of eunuchs), and finally the word ‘shaath’ (which means queer or deviant), there is no shortage of words to describe homosexual acts in Arabic, though none are positive. – Saleem Haddad

In fact, for many queer Arabs, frank discussions of sex often happen in English or French. Perhaps those languages offer a more comfortable distance, a protective barrier between an individual and their sexual practices. Arabic: serious, complex, and closely associated with the Quran, can sometimes appear too heavy, too loaded with social and cultural baggage. Perhaps this reason may explain why many Arab writers choose to write about their homosexuality in English or French, myself included. English provides us with a safe distance: from our communities, and perhaps in some way from ourselves. – Saleem Haddad

Over the last twenty years of LGBTQ activism in the Arab world, some activists have made a concerted, and somewhat successful, effort to re-appropriate and re-shape the language around queer identities. The word ‘mithli’, for example, which is derived from the translation of the phrase ‘homo’, and which reframes the language from a focus on same-sex practices towards describing same-sex identities, is now seen as a more respectful way to refer to gay and lesbian individuals. However, while the word mithli has caught on in media and intellectual circles, the word for ‘hetero’, ghayiriyi, remains unused—thereby rendering the heterosexual identity invisible, signifying it’s ordinariness, while in turn differentiating the ‘homosexual’ with their own unique word: mithli. Perhaps in recognition of this, some movements, in turn, have sought to move beyond the hetero/homo binaries altogether, by Arab-izing the word ‘queer’ into ‘kweerieh’. – Saleem Haddad

Reclaiming words and finding spaces for our identities in them allows us to take ownership over language. After all, what purpose does language serve if we are unable to modernise it, to mould it, shape it, and, ultimately, find a space for ourselves in its words? – Saleem Haddad

.

.o

all my 2016 interviews on Queer Literature:

…and, in German:

- Katy Derbyshire (Link)

- Kristof Magnusson (Link)

- Angela Steidele (Link)

- Hans Hütt (Link)

- Martina Minette Dreier (Link)

Kuratoren & Experten am Literarischen Colloquium Berlin:

Queer Literature: “Empfindlichkeiten” Festival 2016:

Ein Kommentar