(Or: Why Windows 8 Scares Me -- and Should Scare You Too)

I was very excited when I saw the first demos of Windows 8. After years of settling for mediocre incremental improvements in its core products, Microsoft finally was ready to make bold changes to Windows, something I thought it had to do to stay relevant in computing. What's more, the changes looked really nice! Once I'd seen the clean, modern-looking videos of Windows 8, the old Windows looked cramped and a little embarrassing, kind of like finding a picture of the way you dressed when you were a senior in high school (link).

So when Microsoft announced that it was releasing a "consumer preview" of Windows 8, I couldn't wait to play with it. So far I've installed Windows 8 on two computers, a middle of the road HP laptop and a mini tablet PC from Japan. I've browsed the web and used Office and even tested our new app, Zekira, on it. My conclusion is that Windows 8 in its current form is very different; attractive in some ways, and disturbing in others. It combines an interesting new interface with baffling changes to Windows compatibility, and amateur mistakes in customer messaging. Add up all the changes, and I am very worried that Microsoft may be about to shoot itself in the foot spectacularly. Even the plain colorful graphics in Windows 8 that looked so cool when I first saw them are starting to look ominous to me, like the hotel decor in The Shining.

Why you should care. The rollout of Windows 8 has very important implications for not just Microsoft but everyone in the tech industry. In normal times, most people are unwilling to reconsider the basic decisions they have made about operating system and applications. They've spent a huge amount of time learning how to use the system, and the last thing they want to do is start learning all over again. That's why the market share of a standard like Windows is so stable over time. But when a platform makes a major transition, people are forced to stop and reconsider their purchase. They're going to have to learn something new anyway, so for a brief moment they are open to possibly switching to something else. The more relearning people have to do, the more willing they are to switch. Rapid changes in OS and app market share usually happen during transitions like this.

Windows 8 is a revolutionary transition in Windows, easily the biggest change since the move from DOS to Windows in the early 1990s. Consider the wreckage that was created by that transition:

--Apple's effort to retake the lead in personal computing was stopped dead

--The leading app companies of the time were destroyed (Lotus, WordPerfect, Ashton Tate, etc)

--IBM was eventually forced out of the PC business

--Microsoft, formerly an also-ran in apps, became the leading applications company, and a power in server software as well

Will the Windows 8 transition be as disruptive? It's impossible to say at this point. But huge changes are possible. If the transition is successful, Microsoft could emerge as a much stronger, more dynamic company, leveraging its sales leadership in PCs to get a powerful position in tablets, mobile devices, and online services. On the other hand, if Windows 8 fails, Microsoft could break the loyalty of its customer base and turn its genteel decline into a catastrophic collapse. The most likely outcome, of course, is a muddled middle. But based on what I've seen of Windows 8 so far, I am a lot closer to the rout scenario than I expected to be.

Whatever the outcome for Microsoft, what's certain is that because so many people use Windows as the foundation of their computing, the transition to Windows 8 will produce threats and opportunities for everyone else in the tech industry. Play your cards right and your company could grow rapidly. Mess up and you could be the next Lotus. You may love Windows 8 or you may hate it, but if you work in tech you'd be a fool to ignore it.

And yet, most of my friends in Silicon Valley are paying very little attention to Windows 8. Most of them haven't tried it, and don't know a lot about what it does. There are a lot of Mac users in the Valley; they don't think about Windows at all. But even among the Windows users I talk to, the OS isn't a trendy topic; there is a lot more excitement about Android, Facebook, and whatever product Apple just announced.

If you're one of those Windows-fatigued people, it's time to wake up. Here's a summary of my experiences with Windows 8, followed by some thoughts on what it means for the industry...

Listening to Windows 8

The most important message I want you to understand is this: Windows 8 is not Windows. Although Microsoft calls it Windows, and a lot of Windows code may still be present under the hood, Windows 8 is a completely new operating system in every way that matters to users. It looks different, it works differently, and it forces you to re-learn much of what you know today about computers. From a user perspective, Microsoft Windows is being killed this fall and replaced by an entirely new OS that has a Windows 7 emulator tacked onto it.

The main Windows 8 interface is based on Microsoft's Metro design language, which was supposedly inspired in part by the directional signs used in public transportation (link). Metro emphasizes typography (big words in clean fonts) and simple monochrome images, like the signs you'd see on a subway platform.

About Metro. Instead of application icons, Metro features large rectangles (or tiles) in primary colors which are clicked to launch apps, and which can also display live content (like the time or a message). The Metro look is also used in several other Microsoft products, including Windows Phone 7.

I think Metro looks incredibly nice. The graphics are clean and bold, the animations are smooth, and overall it's one of the most visually literate things I've ever seen from Microsoft. I'm still kind of amazed that Metro is a Microsoft product.

The simplicity of Metro is very appealing in many ways, especially when viewed against Apple's interface, which is becoming more and more encrusted with strange textures and bits of faux 3D gewgaw. TK commented on this blog a year ago that Apple is falling into skeuomorphism, a situation in which digital designs retain bits of their physical counterparts even though they're no longer necessary (

link). That theme recently cropped up in an interview with Apple designer Jonathan Ive, in which he ducked a question about Apple's software look by saying he's only responsible for hardware (

link).

Metro is one of the most anti-skeuomorphic interface designs I've seen, which makes it a worthy counterpoint to Apple.

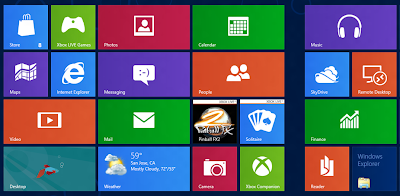

I worry about whether Metro's clean look will last once third parties start adding apps to it. The first few independent Metro apps I've seen use the tile as an advertisement rather than making it blend into the Metro look. Check out the effect:

Just a little bit of this makes Metro look like a scenic highway lined with billboards. That's not much of a step up from today's Windows.

A Microsoft services buffet. The second striking thing about Metro in Windows 8 is that it's a serving platter of Microsoft online services. Most of the tiles you see when you start Windows 8 are Microsoft services, ready to launch with a simple log-in through your Microsoft ID.

Apple has a habit of featuring its own services on its devices, and we all know how Google manipulates Android to feature its tools, but I don't think I've ever seen a platform vendor push so many of its own services so aggressively.

More than a visual change. In addition to its signature look, Metro also dramatically changes how you use the computer. There is no menu bar in the main Metro view, and no file icons. In fact, almost all computer controls are hidden, other than the tiles for launching apps.

To control the computer you have to hover your mouse or your finger in the corner of the screen to bring up a popup set of tools. Lower left is the popup to take you back from an application to the Start screen; lower right brings up an icon bar called Charms for common functions like the control panel.

The Charms bar is the black strip on the right side of the screen.

The main screen is only for launching applications. File management is now separate from app control, and it's not clear to me if you're even expected to manage files in Metro. Like the iPhone and iPad, files are more or less hidden, or managed within individual applications. If you want to deal with them directly, you're apparently expected to use Windows 7 compatibility mode (see below).

Separating app and file management is an interesting move, and I kind of like it in theory. It was never completely intuitive that in the Mac/Windows desktop metaphor, some icons represented tools while other icons represented your documents. The desktop metaphor implied that you were dealing with pieces of paper that you could move around and store in various places, so why could you drag around an application the same way you could drag around a document? In terms of the metaphor, this was like storing your stapler and telephone in a file cabinet. Early versions of Mac and especially Windows created all sorts of strange workarounds to ease management of files and apps, and prevent confusion between them. Microsoft created the Start menu, Apple added the icon dock at the bottom of the screen. Both were basically kludges that papered over holes in the metaphor.

But they were kludges that we've all become accustomed to. Every Windows user is now trained that you use the Start menu to launch apps and manage the computer. There is no Start menu in Metro, so you're going to have a lot of deeply confused people fumbling around trying to find critical computer functions.

This might be easier to manage if there were a new metaphor to Metro that would make it intuitive to guess where the functions are now located. That was part of the strength of the desktop metaphor. You had files, and folders that contained files, and applications that acted on the files. Apple even called some of its early applications desk accessories. This let people guess fairly reliably at how to use the computer, and where to find the things they were looking for.

But Metro doesn't have a central metaphor. Or maybe I should say that its central metaphor is very limited. Subway signs are effective for displaying small amounts of information, but nobody uses a subway sign to carry out a task. Metro biases Windows 8 toward information consumption rather than creation, a recurring theme that I'll discuss more below. That may be great for a media tablet, but what does it do for someone who uses Windows for business productivity?

I'm drawn to a quote from the Jonathan Ive profile that I referenced above. He said:

"Simplicity is not the absence of clutter, that's a consequence of simplicity. Simplicity is somehow essentially describing the purpose and place of an object and product. The absence of clutter is just a clutter-free product. That's not simple."

There are times when I feel like Windows 8 is focused too much on being clutter-free, at the expense of complicating the things that most people do with PCs.

There is a second user interface in Windows 8, and it looks like traditional Windows. You get to it by clicking a Metro tile called Windows Explorer. Windows Explorer (not to be confused with Internet Explorer) takes over the screen, and makes the the PC look a lot like Windows 7, with a few minor cosmetic tweaks and a couple of very important deletions.

It's the deletions that worry me about Windows 8. The most successful OS transitions in history allowed users to keep using their old habits and applications while they gradually got used to the new stuff. For example, Windows coexisted with MS-DOS for many years before it took over the PC (as Microsoft lovingly detailed in a long post

here). I can tell you from personal experience that Apple found it almost impossible to convert PC users to Mac during the Windows transition, because there was no point at which the DOS installed base felt abandoned. They could continue using the old DOS commands for as long as they wanted, until they felt ready to move to Windows.

To Microsoft's credit, it is enabling old Windows applications to continue to work in Windows 8. But some other key features of Windows are being removed, forcing users to switch to the Metro equivalents now, whether they feel ready or not.

The paragraphs below describe some of my concerns about Windows 8. (If you'd like to see a demo of the problems, watch the video).

The Start menu is gone. As I mentioned earlier, there is no Start menu in Metro. That's not such a big deal -- you expect changes like that in a new interface. But the Start menu has also been removed from Windows Explorer. It's no longer present

anywhere. If you're not familiar with Windows, you won't understand how central the Start menu is to a Windows user. It's the thing you generally use to turn the computer on and off, launch applications, open file folders, search, and access the control panel. Recent changes have also made it a preferred place for directly opening documents.

In Windows 8, the functions formerly done by Start have been spread across several locations, some in the Metro interface and some in Windows Explorer. So Windows users moving to Windows 8 will have to learn parts of Metro before they can get

anything done. In some cases, common functions formerly available through a single click in Start have been buried several clicks deep within Metro.

If you're not a Windows user, it is hard to describe how disorienting this is. It's roughly equivalent to giving someone a car in which the steering wheel has been replaced by a joystick. Not only do you need to learn how to steer with a joystick, but all of the controls formerly attached to the steering column are now scattered in various spots on the dashboard. The wiper control is a lever above the radio, the high beam lights are a switch on the rearview mirror, the turn signal is a set of buttons under the speedometer, and the cruise control is a dial hidden inside the ashtray. Oh, and you honk the horn by bouncing up and down in your seat.

The car's designer will give you logical explanations for every change they made in the car, just as Microsoft can explain the reasons for removing Start. For a new user they may all make sense. But for an existing user, the removal of Start forces a huge amount of re-learning. An existing Windows user can't just sit down with Windows 8 and start using it. They'll need some sort of tutorial and reference system to show them how to use it, and to answer questions when they get confused.

Microsoft has not forced discontinuities like this in past transitions. The best example is the preservation of the DOS command line interface, the equivalent of the Start menu for people who used DOS. The command line function has been available in every version of Windows to date, and in fact it's still supported in Windows 8.

The dreaded DOS-style command line in Windows 8.

Control panels are missing. Many of the old control panel functions from Windows are accessible through the Settings Charm in Metro. But some of them aren't. I don't know if that means Microsoft hasn't finished adding them to Metro, or if they have decided to eliminate some controls. Based on what Microsoft has said online, I think it's the latter -- one recurring theme in Metro is that Microsoft is trying to hide some complexity in order to make the OS more approachable. I understand the motivation, but for an existing user this actually makes the OS more complex.

Case in point: in Metro I can't find a power management function allowing me to control when my laptop sleeps and how much power it uses when running on batteries. I looked through every tab in the Metro settings, and finally realized the function just wasn't there. After searching online, I found a way to access the old Control Panels through Windows Explorer. But it's not in an intuitive place.

For a user, there's no easy way to tell if a particular control panel feature has been relocated to a new spot in Charms, eliminated, or hidden within Windows Explorer. You just have to fumble around and cuss for a while until you figure it out.

How do I turn this thing off? The concept of a power button is pretty central to any electronic device. You turn it on in order to use it, and you turn it off when you're done. It's easy to turn on a Windows 8 computer; you just press the power button on the computer. But pressing the button again does not turn off the computer. Instead, it puts the computer to sleep.

Sleep is a good thing in a computer. It lets a computer restart quickly, and keeps your apps active. But it does consume power, which is an issue for ecologically-conscious desktop users, and a primary concern for laptop users. Also, I find that it's helpful to turn off Windows from time to time because the OS gradually becomes confused and slow as you launch and quit large numbers of apps. So I expect to be able to easily turn off my computer, and I think most Windows users will feel the same way.

It is absurdly difficult to turn off Windows 8. So difficult that there are entire web pages devoted to tutorials on how to do it. CNET wrote an unintentionally hilarious article detailing four different ways to turn off Windows 8, each more baroque than the last (

link). Here's what CNET called the "most basic" way:

"In the Metro interface, hover your mouse over the Zoom icon that appears in the lower right corner of the screen. The Charms bar should then pop up displaying several icons. Moving your mouse up the screen will reveal the names of each icon, including Search, Share, Start, Devices, and Settings. Click the Settings icon and then the Power Icon. You should see three options: Sleep, Restart, and Shut down. Clicking Shut down will close Windows 8 and turn off your PC."

So shutdown requires five actions: a hover, a sweep, and three clicks. Plus the command is hidden in a very non-intuitive place. People used to joke that only Microsoft could think it was intuitive to have the Shut Down command hidden under the Start button. I think it's sooooo much more intuitive to have it hidden under Settings.

I don't know why Microsoft chose to make it so hard to turn off Windows 8. Some of the online reviews have suggested that Microsoft believes people should only put their computers to sleep instead of turning them off. Maybe, but that's a pretty controlling assumption, especially for laptop users. Or perhaps Microsoft optimized Windows 8 only for tablets and views the entire PC thing as an afterthought.

Whatever the intent, I am concerned that it's so hard to perform such a common function. But what's much more alarming is that there are several redundant, complex ways to perform that common function. When that happens, it's usually a sign of confusion in the development team.

Windows 8 is not designed for PCs. I know that's a very sweeping statement, but in a couple of areas Windows 8 is clearly designed to work better for media tablets than for traditional personal computers. The first is the general architecture of the interface. Despite Microsoft's protestations to the contrary, Metro is clearly optimized for use on a touchscreen device rather than a keyboard and mouse PC. You can force it to work with a mouse, but many of the things you have to do feel awkward, and are more complex than their old Windows equivalents. One good example is the finger swipe, which works very well with a touch screen but is unpleasant on a notebook computer because you can't easily click and drag on a trackpad for long distances. Parts of Windows 8 (for example, logging in to the computer) require finger swipes.

I long to see what Metro could do on a PC equipped with a gesture recognition system like Kinect. That might be a revolutionary change worth migrating to. Microsoft says that is coming, but Kinect, Metro, and Windows 8 are not yet fully integrated (

link). That's unfortunate, since developers are working on Metro apps now.

Windows 8 is also designed with tablet-like tasks in mind. Productivity and information creation tasks are compromised to make the OS more attractive for content consumption. Microsoft was very explicit about this in some of its online commentary (

link):

"People, not files, are the center of activity. There has been a marked change in the kinds of activities people spend time doing on the PC. In balance to “traditional” PC activities such as writing and creating, people are increasingly reading and socializing, keeping up with people and their pictures and their thoughts, and communicating with them in short, frequent bursts. Life online is moving faster and faster, and people are progressively using their PCs to keep up with and participate in that. And much of this activity and excitement is happening inside the web browser, in experiences built using HTML and other web technologies."

Let me translate that for you: "We're optimizing Windows for using Facebook and YouTube at the expense of performing productivity tasks." Which is fine; it's a design choice Microsoft is free to make. But it's going to have an impact on the large base of people trying to get work done with a PC.

Incomplete support of existing hardware. In the first announcements of Windows 8, Microsoft bragged about how efficient it is. The company said explicitly that it would put less burden on hardware than Windows 7, and demonstrated Windows 8 running on old low-featured computers (

link). In several places I've seen Windows 8 described as a great way to revive an old laptop. Unfortunately, although Windows 8 may have a light hardware footprint, it has compatibility problems with some existing hardware, including some Windows 7 computers. Computers designed for Vista can have much more serious problems. This became very clear to me when I installed Windows 8 on my Vista-based mini tablet PC. Windows 8 is not compatible with the wireless network chips in my tablet PC, so it can no longer connect to the Internet.

More importantly, the touch screen isn't fully compatible with Windows 8. I can't get the system to recognize taps in the outer half-inch of the screen, meaning that I can't activate the Metro Start function or the Charms panel. Fortunately, my tablet PC has a keyboard, so I can use the trackpad to control it. But who wants a tablet PC that doesn't have a working touch interface?

The severity of this problem varies from computer to computer, but it's apparently fairly common. For example, here's video of an Acer user with some of the same troubles, although not as severe as mine (he can activate the controls some of the time;

link).

There is no workaround for this problem other than buying a new computer. So its promise of running well on existing hardware turned out to be an exaggeration.

Microsoft recently discussed the problem in an elaborate blog post describing touch screen compatibility under Windows 8 (

link). The tests documented by Microsoft show a lot of Windows 7 devices interpreting gestures properly only 70% to 80% of the time (the ratio is even worse for some features). A success rate of 95% is required for Windows 8 certification, so a lot of Windows 7 touchscreen computers (Microsoft doesn't say how many) would fail to pass certification. The article concludes:

"The vast majority of Windows 7 touchscreens can be used with Windows 8...with a reasonable degree of success."

I applaud Microsoft for coming clean about the problem, but I hate to see them use those qualifiers in their statements. Lawyers love words like "vast majority" and "reasonable degree" because they sound good but don't quantify anything, so you can't be sued. The reality is that if you want to be sure Windows 8 will work at its best, you should buy a new computer bundled with it. This is especially true of touchscreen PCs, the devices that stand to benefit the most from Metro's touch oriented features.

I don't actually have a problem with that. Providing backward compatibility is always difficult when you upgrade an OS, and considering the complexity of the Windows hardware base, it would be surprising if everything worked right. However, what I do have a problem with is that other parts of Microsoft are ignoring the subtle compatibility story and continuing to claim that all Windows 7 hardware is fully compatible.

For example, Antoine Leblond, the VP of Windows Web Services, implies that Windows 8 will run on every Windows 7 device (

link):

"We’ve just passed the 500 million licenses sold mark for Windows 7, which represents half a billion PCs that could be upgraded to Windows 8 on the day it ships. That represents the single biggest platform opportunity available to developers."

Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer continues to quote that half billion number in public (

link).

This isn't just misleading to customers and developers, it may also hurt Microsoft by setting unrealistic expectations. If twenty percent of the Windows 7 installed base upgrades to Windows 8 in the first three months, is that a raging success or a humiliating failure? I might view it as a very promising start, but Microsoft's own hype says it would be a disaster.

Failing to warn users of potential problems. Speaking of miscommunication, Microsoft didn't clearly tell users that the Windows 8 preview is a one-way installation. The word "preview" implies to many people an advanced sample that you can play with for a while and then toss aside. But unless you have the original installation disks that came with your computer, the Windows 8 preview replaces your current OS and can't be removed. Even if you do have those disks, on many PCs (including mine) the factory install disks wipe the hard drive and do a new install from scratch, deleting all your files and applications.

Microsoft did disclose this information on the Windows 8 preview site, but the disclosure was written in bureaucratic language that didn't make clear the risk, and what's worse, that text was below the "Install" button, meaning a user could easily miss it. (In the latest version of Microsoft's site, the automated installer for Windows 8 has been removed [gee, I wonder why] and you can only install by burning an installation disk on a DVD. That makes it much harder for casual users to install the preview, and the warning is now above the download links.)

If you want a measure of how many people missed the warning, do a web search for "uninstall Windows 8." Be prepared to read some angry commentary.

I think the next round in this cycle of frustration is going to come early next year, when the Windows 8 preview expires and preview users are required to purchase Windows 8 to keep their computers working. The fact that there's an expiration date on the preview is something else that Microsoft didn't prominently disclose.

What it means. I could go on, but I hope you get the idea. Windows 8 is a very interesting, provocative, even courageous product. But I'm not sure it's going to succeed. My concerns are in two areas. The first is that I'm not sure what burning problem Windows 8 solves for what group of users. If you're a productivity worker, Windows 8 does very little for you, and in fact probably makes your life harder. If you're most interested in entertainment and accessing online content, Metro is a big improvement over Windows -- but aren't you likely to already have a smartphone or tablet?

My second concern is the emotional feel I get from Windows 8. I know that's a really vague comment, so let me try to tie it down a bit. I think I'm a fairly sophisticated user. I've used every version of Windows since 2.0. When I worked in the competitive team at Apple, we tested every bizarre computer operating system we could find around the world, including stuff written in Japanese with no English-language documentation. We made all of it work. But there are still some parts of Windows 8 that I haven't been able to figure out, and other parts that I understand but that annoy me every time I touch them.

Because of its problems, Windows 8 isn't fun to use, at least for me. Whatever sense of joy I get from the cool new graphics is outweighed by a feeling that my productivity is being reduced. Think of the best new app or website you've ever discovered; the feeling you got the first time you understood the power of Twitter or you created a presentation and it came out looking great. That feeling of empowerment and excitement is critical to getting people started with a new technology. But Windows 8 makes makes me feel limited and cramped. It isn't a launch pad, it's a cage.

If Windows 8 is a problem for me, what's it going to do to a typical Windows user who just wants to get work done and doesn't have time to learn something new? And what sort of support burden is it going to put on the IT managers of the world?

What works well. Out of fairness to Microsoft, I should tell you that there are some things about Windows 8 that I love. It looks beautiful. On my computers it's pretty darned fast for a lot of functions (for example, booting and switching in and out of the Start screen). Other people have reported some performance problems, but I expect those in what's essentially beta software. An OS almost always gets faster right before it ships, because the last thing the engineers do is strip out all the diagnostic code they were using to track bugs.

For the control panel functions that Microsoft chose to implement in Metro, I think the interface is much cleaner and more intuitive than it was in the horribly overloaded Windows Control Panel. This is where you'd expect Metro to shine, because it's optimized for giving directions, and a control panel gives directions to your computer. I was also delighted to see a function in Windows 8 called "Refresh your PC without affecting your files." Every Windows user knows that the performance of Windows goes south after a year or two as various bits of software gunk build up. Unfortunately, the refresh function does erase your third party apps (unless you got them through the Windows 8 store). If Windows 8 had a "refresh my PC without deleting my third party applications" function, I'd upgrade just for that.

Unfortunately, that's not the only feature of Windows 8.

Impact of Windows 8

For Microsoft: A huge roll of the dice. I've spent the last several weeks asking myself why Microsoft chose to remove some Windows 7 features and exaggerate the prospects for Windows 8.

There are many possible explanations. It could just be arrogance -- they believe they can force customers to do what they want. It could be an excess of designer zeal -- designers always think people will fall in love with their creations once they try them.

But it could also be insecurity. To me, it feels like Microsoft is in a quiet panic. When Apple says the era of the PC has ended, I think Microsoft may believe it even more than Apple does. Smartphones eat away at messaging, tablets compete for browsing and game-playing, and who knows what will come next. In the new device markets, Microsoft is an also-ran. I think Microsoft feels it must find a way to leverage its waning strength in PCs to make itself relevant in mobile.

Step one is to deploy the same look and feel on all classes of devices, so people have an incentive to use only Microsoft products. Microsoft tried first to take the Windows look and feel to mobile devices, but that failed because it was too ugly and hard to use. So instead, Microsoft is now replacing the Windows look and feel with something designed for mobile.

The second step is to undercut the iPad (and Android tablets, if they ever start to sell) by selling PCs that also work great as tablets. Microsoft's pitch is that instead of buying a separate PC and tablet, you should buy one thing that bridges both usages. So we should expect a big push for convertible Windows 8 touch notebooks this fall.

Step three is to drive the transition to Metro as quickly as possible. I think Microsoft is scared that it might be permanently closed out of the new markets, so it wants to force people onto Metro before that happens. I believe that's really why it eliminated the Start menu. If Start is still there, Windows users could live for years without learning much about Metro. But with Start gone, Windows users will have to use bits of Metro now, and Microsoft believes they'll naturally embrace it once they've been forced to use it.

Here's what Microsoft itself said in a blog post about the Windows 8 interface (

link):

"Fundamentally, we believe in people and their ability to adapt and move forward. Throughout the history of computing, people have again and again adapted to new paradigms and interaction methods."

I always get scared when a designer talks about the inevitability of people accepting a change. It's like you're counting on some mystical law of nature to cause a migration, rather than enticing people to move by giving them something that works better than what they have today. That's how the DOS to Windows transition worked -- people could (and did) continue to live in DOS for years until they learned how much more they could get done with Windows. But Microsoft has decided to force the issue. Then it rationalizes the decision with bromides like "we believe in people" and "the DOS users complained a lot too and look how that turned out."

There can come a point where a company is so committed to a plan that it stops listening to complaints from its customers. It feels like Microsoft may have reached that point. If you complain about your inability to uninstall Windows 8, the problem is that you failed to read the fine print. If you complain about the Start menu being missing, the problem is that you just don't have enough faith in humanity.

But the real lesson of history is not that you've got to have faith, it's that when people are forced to adopt a new computing paradigm they look around and reconsider their purchase.

There's a range of possible outcomes from the Windows 8 launch:

1. Windows users adopt Windows 8 enthusiastically. I turn out to be a whiner. Most Windows users don't miss the Start menu, and they fall all over Windows 8 in glee. Microsoft gets a nice revenue bump from all the upgrade sales, and the Windows licensees, sensing big opportunities, jump in with great new convertible tablet designs that make the iPad look tired. App developers create astounding new Metro programs that make things like Office and Photoshop obsolete. Microsoft's online services become dominant because of their ties to Metro. The aura of success around Windows 8 drives increasing sales of Windows Phone, rescuing Nokia from irrelevance. Android tablet is obliterated, and sales of Android phones stall out as customers start to choose Windows Phone instead. The big Asian phone companies recommit to Windows Phone and move their best engineering teams onto it. Wall Street analysts short Apple's stock, declaring the era of iEverything over.

2. Windows users cling to Windows 7 tenaciously. In this scenario, Windows 8 becomes the new Vista. Microsoft's anticipated revenue from Windows 8 upgrades does not materialize, hurting the company's stock price and forcing layoffs to maintain earnings. Microsoft's hardware partners are left with big stockpiles of unsalable Windows 8 PCs which they have to write down. This accelerates the share growth of the Asian PC makers, who can best withstand a price war. HP kills its PC division, and Dell is in deep trouble. Developers who bet on Metro have to live on canned tuna and string cheese. Nokia, stuck with a minority platform that European operators don't want to carry, wrestles with huge cash flow problems.

3. Windows collapses. Millions of Windows users, disenchanted with the changes in Windows 8, decide to switch to some other computing platform. Microsoft's revenues drop alarmingly, and Windows 8 is labeled a failure, causing even more customers to migrate away in a self-perpetuating collapse of the Windows installed base. Windows Phone is swept aside, turning Nokia into the "Finnish RIM". Microsoft survives as a fragment selling Office and some server software.

The interesting thing about these scenarios is that the Windows installed base will choose the winner. If the Windows users are enthusiastic, Microsoft prospers. If they're passive, Microsoft suffers. If they turn negative. Microsoft dies a gruesome death. So you'd think that Microsoft would do everything in its power to make current Windows users feel comfortable and excited about moving to Windows 8. Instead, they're being confronted with deliberate incompatibilities, indifference toward their needs, and a preview campaign for Windows 8 that has already disenchanted some of the most enthusiastic Windows users.

Do you think I'm exaggerating? Do a web search for "I hate Windows 8" vs. "I love Windows 8." Here's what you'll find:

The rule of thumb for online comments is that for every message someone posts, another ten to 100 people feel the same way. That means there may be several million Windows users already disenchanted by Windows 8, before it even ships.

Does that look like a blockbuster launch to you?

Note: I deleted the chart and text above because, as Dana on Seeking Alpha pointed out, the search I quoted appears to be wrong (link). I don't know how I messed that up, and I apologize for the incorrect information. The search I quoted showed "hate" exceeding "love" by about 3:1. The reality is that apparently there are many more "I love Windows 8" comments than "I hate Windows 8", so I may be overstating the negative reaction.

What Microsoft should do. I believe Microsoft is overestimating the immediate risk of a collapse in PC sales due to tablets and other new devices, and underestimating the potential backlash against Windows 8. A tablet -- any tablet -- just isn't a good substitute to a PC for many tasks. Huge numbers of people still need PCs for productivity work, and won't abandon them quickly, if at all. And no matter how much Microsoft tells itself that people are adaptable, the average Windows user is intensely practical and focused on getting work done rather than exploring magical new experiences.

Ironically, the biggest danger of a sudden collapse in PC sales comes from Microsoft's own effort to force users onto Metro.

The answer is very simple: Put the $%*!# Start menu back in Windows Explorer. Apologize for the confusion, and explain that you've learned from your customers. Then focus your work on making Metro apps so exciting that people want to migrate to it.

What will happen? I doubt Microsoft will be willing to back down on eliminating the Start menu. The company has invested too much ego in the decision at this point. As a result, the runaway success described in Scenario 1 is very unlikely to happen. I think scenario 2 is the most likely, if only because Windows users have already refused past migrations, and it's easy to stick with a behavior you know. I would have called scenario 3 impossible a year ago, and it's still not likely. But the more problems I see with Windows 8, the more I begin to believe it could happen.

But a lot depends on the actions of Microsoft's competitors. You can't have a mass migration away from Windows unless there's a strong alternative to it. That brings us to a discussion of Apple.

What will Apple do?

Ahhh, Steve. If only you were around to see this.

Twenty-five years ago Microsoft copied the Mac interface and confined Macintosh to a tiny sliver of the PC market. Despite all the progress you've made since then, Macintosh continues to command under 10% of the worldwide PC market. But now, at long last, Windows is vulnerable to a potential knockout. If the Windows 8 transition is as uncomfortable as I expect, you might be able to peel away large numbers of PC users and trigger a collapse of Windows sales.

You'd have to make some compromises, creating special Mac bundles with Windows emulators and file migration tools. And you'd have to jump back into doing Mac vs. PC advertising, this time welcoming the guy with the dorky jacket into your club. It's risky, and in some ways it's backward-looking at a time when Apple is looking forward to conquering television and maybe the auto market. But the PC market is worth about $300 billion in revenue a year, at a time when it's becoming harder to maintain Apple's sales growth. Where else can you so easily tap into that big a pool of revenue? Besides, how cool would it be to finally be the leading PC platform in the world again, after all those years? Talk about changing the world...

If Steve were here, I think he'd be sorely tempted to attack. I don't know what Apple's new management will do. But somebody in Redmond ought to be really scared of the possibility.

What about Google?

I'm sure I'm going to get messages saying that Chromebooks are a great substitute to Windows. Others will say this is the big opening for Android tablets.

I don't see it. Apple has at least a theoretical shot at Windows users because it has a complete personal computing platform plus the ability to add Windows compatibility to it. After Windows 8, Apple can claim to have a better PC than the PC. At this point, Google can't make that claim credibly. Moving from Windows to either Android or Chrome would be a step down in productivity for most Windows users; more of a step down than Windows 8.

What Google should be thinking about, very hard, is the scenario in which Windows 8 is at least a partial success. Android has a lot of momentum in smartphones, and will be very difficult to displace quickly. But in tablets, Android is a very weak alternative to iPad. I could picture a situation in which Windows 8 tablets become the iPad alternative, giving Microsoft a beach-head it can pour resources into. If Windows 8 gets a toehold in any category, that could have a big effect on the phone market over time.

I think many Android phone licensees are quietly looking for alternatives. One of the original attractions of Android for hardware licensees was that it's royalty-free. But the seemingly endless series of IP lawsuits against Android licensees have convinced many of them that Android isn't any cheaper in reality -- what you save in up-front licensing costs you lose in attorney fees, patent licenses, and general jerkiness by the OS vendor. It doesn't help that Google just bought a major hardware company and is strongly rumored to be planning its own line of tablets designed to lower the entry price point for tablet computing.

Goody, think the licensees,

now my own OS vendor is going to commoditize me.

At this point I think the main thing still holding licensees to Android is its sales momentum. And that's a huge inducement. Sales momentum matters to licensees more than anything else. But that also means that if Windows gains some momentum, the licensees will be all over it. They won't abandon Android, but the big companies like Samsung will look to create a balance between Google and Microsoft, so they can play them off against one another.

What it means to web companies

If you work at someplace like Facebook or Twitter, you probably think this article isn't relevant to you. Who cares what happens to Windows? Let the old dinosaurs fight it out in OS, your world is online and the desktop doesn't matter to you.

If that's your thinking, I invite you to look again at that Metro start screen:

Those tiles, the first thing a user sees when starting Windows 8, almost all launch Microsoft online services. They include:

--An app store

--Maps

--Video

--Photos

--Messaging

--Mail

--Weather

--Calendar

--People

--Camera

--Music

--SkyDrive

--Finance

--Four Xbox-related items

--Reader, and

--A browser (Internet Explorer)

In other words, Windows 8 showcases Microsoft's equivalents to many of the most popular online services from Facebook, Google, Yahoo, and Apple. Many of the apps are gorgeous, by the way. Here's a sample of Bing Finance in Metro:

Imagine 90% of the world's computer-using population seeing those tiles every day. How long before they click on one of them out of curiosity? And if they like that one, how many more will they try? Picture Microsoft pushing new tiles into Windows 8 whenever it wants to compete with another web service. And remind yourself that platform transitions usually cause people to reconsider their app choices.

If you still think you can ignore Windows 8, go right ahead. But if I were you, I'd be preparing a Metro version of my tablet app, very quickly.

What to do if you're an app developer

This is the hardest question to answer. Platform transitions create a wonderful opportunity for developers because customers are most willing to look at new apps when they first try a platform. If you get in there early with a great Windows 8 Metro app, your company might take off spectacularly. If a competitor does Metro first, you'll be vulnerable.

On the other hand, if you bet big on Windows 8 and it fails, you'll be stuck. Even if it just sells slowly at first, you could easily run out of money before Microsoft fixes the problem. A poor quarter is a bump in the road for Microsoft; it could be an extinction event for you.

If I were creating a new application today...oh, wait, I am creating a new application today. So here's how the situation looks to me:

If you have a PC app today, should you be sure it works on Windows 8? Yes, of course. At the minimum, make sure it runs in Windows 7 compatibility mode.

Should you we revise the app to take advantage of the Metro interface? If you have a bunch of extra money, sure. But if you're not awash in surplus funds, I would hold off for now. It's a risk, but I think most Windows 8 users are going to linger in traditional Windows mode for a long time, and that's the market you need to serve first.

When should you do Metro? When Microsoft demonstrates significant sales volume of genuine Metro users. The best way to track this is probably sales of Windows 8 tablets, as opposed to PCs preloaded with Windows 8. You don't know how many Windows 8 PCs are having Windows 7 backloaded onto them, but a tablet with Windows 8 is probably running Metro.

The next question at that point will be who's buying those Metro tablets and what are they being used for. Are they being bought for entertainment? If so, you probably don't want to port your business app to it.

Conclusion

Here's what I'd like you to take away from this article:

--Windows 8 is not Windows, it's a new operating system with Windows 7 compatibility tacked onto it.

--Although Windows 8 looks pretty and is great for tablet-style content consumption, I question its benefits for traditional PC productivity tasks.

--Big OS transitions like this one traditionally cause users to reconsider their OS decision and potentially switch to something else.

--Microsoft has worsened the risk that people will migrate away from Windows 8, by disabling some key features of Windows 7, and mishandling the consumer "preview" program.

--However, people won't necessarily abandon Windows because it's not clear if they have a good alternative to it.

--Apple could provide the best alternative if it chooses to. This might be Apple's best chance ever to stick a fork in Windows.

--If Windows 8 is even moderately successful, it could weaken Google and the big web services companies. The trend toward bundling web services into the OS is potentially very disruptive to the web community, and they should be quite worried about it.

--If you're a PC app developer, you should probably hold off on Metro because it's not clear how quickly its user base will grow.

What do you think?

Thanks for sticking around through a very long article. I'd like to hear what you think; please post a comment. Do you believe Windows 8 will take off? Should app developers support it now? Would you change anything in it? If so, what?

Corrected on May 29, 2012.