By PATRICK MCGROARTY And KATHLEEN CHAYKOWSKI

JOHANNESBURG—When South African President Jacob Zuma called this week for an end to whites' monopoly on the continent's biggest economy, he jump-started the debate surrounding his party's core pledge to transfer more farms to blacks.

The push to empower the country's black majority is a potent political rallying cry—but it also points up a shortcoming for Mr. Zuma's African National Congress, which has largely failed in its attempts to turn that pledge into reality.

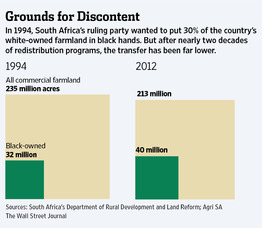

At the end of apartheid in 1994, blacks owned a small share of the country's farmland. The party wanted to transfer 30% of white-owned farmland to blacks by 1999; more than a decade later, it has transferred only 7%.

"Drive around South Africa and stretches and stretches of land belong to white farmers. And yet there are people crammed in a village," Mr. Zuma told reporters at the ANC's policy conference this week, saying the imbalance needed to be corrected.

Program Pairs Black Farmers With White Mentors

The push is important to Mr. Zuma's hopes for retaining South Africa's presidency. His party's left-wing youth league has called for land to be seized without compensation from white farmers. Top ANC officials have rejected such tactics in favor of continuing to buy land from willing sellers and giving it to black aspiring farmers. But Mr. Zuma is also eager to appear sympathetic to the broad aims of the ANC's left-leaning members as he seeks to be re-elected as the party's leader, which would all but secure his path to re-election as president in 2014.

South Africa's cattle ranches and orchards are the envy of Africa. More than 80% of its farmland remains white-controlled, though the dwindling white population accounts for less than one-tenth of the country's 50 million people. Few rural youths want to follow their parents into farming.

The number of white commercial farmers in South Africa is dropping—from 60,000 in 1994 to 37,000 today, according to Theo de Jager, deputy president of Agri SA, a commercial farmers' association—as many consolidate farms into larger commercial operations.

Mr. de Jager said a new generation of black farmers must fill the void. "They need to stand on their own feet and make a profit from what they produce," he said. "If they all fail, we're going to fail with them."

But a limited number of blacks have the capital for equipment, seeds and taxes. The ANC's challenge is to fund, amid a struggling economy, efforts to buy farms for blacks and then to provide seed money for supplies. It must also avoid the steep drop in productivity that neighboring Zimbabwe experienced a decade ago when allies of President Robert Mugabe drove whites off their farms—often violently—prompting an exodus of capital and skills.

As ANC officials met privately this week to set the party's land-reform agenda for the next five years, a look at recent efforts to help black farmers shows the process is likely to remain slow and risky.

At least one government program is beginning to bear fruit, as one black South African farmer's experience shows. But his success was hard-earned, as much a result of chemistry between the farmer and a mentor as of the government's financial assistance.

Three years ago, Gift Mafuleka quit his work as a crop manager for McCain Foods Ltd., a Canada-based frozen-food company, to try his hand in farming. Backed by a pension he earned during his three years at McCain, he started farming 845 acres the government purchased for him in Bronkhorstspruit, east of the capital, Pretoria.

The farm quickly foundered. After three months, Mr. Mafuleka had spent his pension on basic agricultural supplies.

Then Tim Hedges, Mr. Mafuleka's former manager at McCain, dipped into his own pocket for the black farmer, giving him $2,400 over four months to make sure he could support his land and a new baby.

In 2010, the pair entered the Recapitalization and Development program, which pairs a novice black farmer with a mentor who helps the farmer form a business plan. New farmers receive up to $500,000 to invest in equipment, seed and livestock. Mentors get a monthly stipend of $600.

Mr. Hedges helped Mr. Mafuleka secure loans from prospective buyers of his peas, corn, soybeans, cabbage and cattle. He also introduced him to a senior manager at Massmart Holdings Ltd., the South African retail chain in which Wal-Mart Stores Inc. acquired a majority stake last year. Massmart managers ordered a one-harvest trial run of 50,000 heads of cabbage to be delivered this month.

If the trial goes well, both farmer and mentor said, Mr. Mafuleka will deliver more. A spokesman for Massmart didn't respond to calls or emails seeking comment.

Mr. Mafuleka, a soft-spoken 34-year-old with a mustache, says his crop operation is profitable and that McCain Foods is buying much of his vegetables. Mr. Mafuleka recently hired two full-time trainees to help him with farmwork. "Tim was a make-or-break for my aspirations," Mr. Mafuleka said.

But the program is far costlier that any redistribution strategy the government has tried before. Since starting it in 2009, the government has spent $122 million a year to support just one in 100 farmers on redistributed land. The tab is fast approaching the $730 million the government has spent buying white-owned farmland since 1994.

The program is one of several training black farmers through partnerships with white counterparts.

In the Eastern Cape province along the Indian Ocean coast, the National Wool Growers Association has paired commercial sheep farmers with several thousand small-scale shepherds. The commercial farmers provide prized breeding stock to the poor shepherds to improve their herds. The farmers in turn buy that wool and weave it into their own bales for export.

In the northern province of Limpopo, Wal-Mart has designated a commercial farmer to mentor 20 first-time black farmers. The commercial farmer is paid based on this mentees' profitability.

Still, the land-reform programs haven't made much of a dent in overall land ownership. And as land prices rise, the government can't buy as much of it.

The goal then is to ensure more productive farms, according to Sunday Ogunronbi, an executive manager in South Africa's department of rural development.

"The government still has not abandoned the target of 30%," he said. "We are just focusing on quality."

—Devon Maylie contributed to this article.Write to Patrick McGroarty at patrick.mcgroarty@dowjones.com

A version of this article appeared June 29, 2012, on page A14 in the U.S. edition of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: South Africa Reseeds Farm Debate.

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/WO-AK251_SALAND_G_20120628200710.jpg) Jason Larkin for The Wall Street Journal

Jason Larkin for The Wall Street Journal

![[SB10001424052702303768104577462820604798022]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-TI324_saland_D_20120612125740.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MK-BV397_SOCCER_A_20120701185645.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-BG867_CRUNCH_A_20120701220017.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MK-BV384_AWOMEN_A_20120701165549.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-BG850_SCYTHE_C_20120629173254.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-TO602_boxila_C_20120628203443.jpg)

![[OB-TO555_spidey_C_20120628175021.jpg]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-TO555_spidey_C_20120628175021.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OD-AS358_CRUISE_C_20120628134552.jpg)

![[image]](https://iza-server.uibk.ac.at/pywb/dilimag/20210113092156im_/http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/RV-AH340_MASTER_C_20120628162030.jpg)

Most Recommended

“Try and fathom the hypocrisy of ...;”

“Perhaps, Mr Gensert, it's not th...;”

“Another thoughtful and concise...;”

“However, Ms Napolitano immediate...;”

“My thought, exactly...You go on...;”