- Das Haus

- Newsletter

- Service

- Publikationen

- Veranstaltungen

- NEU Livestream

- Livestream-Archiv

- Ausstellungen

- Buchmagazin & AutorInnen

- AutorInnen

- AUFTRITTE

- Rezensionen Buch

- Rezensionen 2019

- Rezensionen 2018

- Rezensionen 2017

- Rezensionen 2016

- Rezensionen 2015

- Rezensionen 2014

- Rezensionen 2013

- Pressespiegel 2000-2010

- AutorInnen A

- AutorInnen B

- AutorInnen C

- AutorInnen D

- Autorinnen E

- AutorInnen F

- AutorInnen G

- AutorInnen H

- AutorInnen I

- AutorInnen J

- AutorInnen K

- AutorInnen L

- AutorInnen M

- AutorInnen N

- AutorInnen O

- AutorInnen P

- AutorInnen Q

- AutorInnen R

- AutorInnen S

- AutorInnen T

- AutorInnen U

- AutorInnen V

- AutorInnen W

- AutorInnen Z

- Rezensionen Sachbuch

- Verlage

- Dank an Verlage

- Impressum

- Incentives

- Bibliothek & Sammlungen

- Katalogsuche

- Partnerinstitutionen

FÖRDERGEBER

PARTNER/INNEN

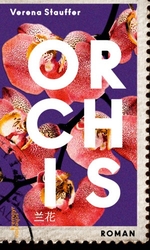

Verena Stauffer: Orchis. Novel. This book takes its readers on a journey into the mid-19th century and exotic locations deep in the Madagascan and Chinese interior. Yet it is nothing like reading a historical novel or an ordinary travelogue: we are given no dates, facts or figures relating to either a concrete topography or a historical chronology. Abridged version of the review by Walter Fanta, 18 April 2018

|

| Veranstaltungen |

|

Sehr geehrte Veranstaltungsbesucher

/innen! Wir wünschen Ihnen einen schönen und erholsamen Sommer und freuen uns, wenn wir Sie im September... |

| Ausstellung |

| Tipp |

|

OUT NOW: flugschrift Nr. 35 von Bettina Landl

Die aktuelle flugschrift Nr. 35 konstruiert : beschreibt : reflektiert : entdeckt den Raum [der... |

|

INCENTIVES - AUSTRIAN LITERATURE IN TRANSLATION

Neue Buchtipps zu Ljuba Arnautovic, Eva Schörkhuber und Daniel Wisser auf Deutsch, Englisch,... |