Please do not shoot the pianist!

Vorgeschlagen von Alf Mayer, Journalist & Literaturkritiker, Autor des Ed McBain-Readers „Cops in the City“ (zusammen mit Frank Göhre) und CrimeMag-Redakteur, lebt in Bad Soden am Taunus.

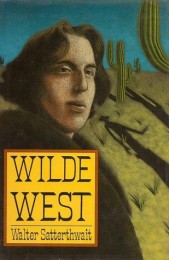

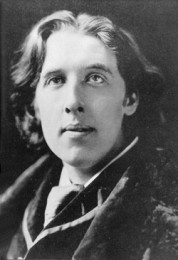

„The youth of America is their oldest tradition. It has been going on now for three hundred years“, lautet einer der berühmten Aphorismen von Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900). Zwei Mal war er in Amerika; die erste Reise, 1882, dauerte ein Jahr. Er gab dabei 140 „Lectures“. Walter Satterthwait nutzte diesen Stoff 1991 für seinen Kriminalroman „Wilde West“ (dtsch: Oscar Wilde im Wilden Westen; bei Haffmans erschienen), wo der Dichter es als eine Form des Stalkings mit einem seine Tour verfolgenden Serienmörder zu tun bekommt. Aus Amerika zurück, entwickelte Wilde 1893 den Vortrag „Impressions of America“ (aka „Personal Impressions of America“), mit dem er durch Europa tourte. Stuart Mason, sein späterer Biograph, machte daraus eine Broschüre, die im März 1906 in einer Auflage von 500 Exemplaren erschien. Wir zitieren daraus in der Originalsprache.

Oscar Wilde: Impressions of America

I fear I cannot picture America as altogether an Elysium — perhaps, from the ordinary standpoint I know but little about the country. I cannot give its latitude or longitude ; I cannot compute the value of its dry goods, and I have no very close acquaintance with its politics. These are matters which may not interest you, and they certainly are not interesting to me.The first thing that struck me on landing in America was that if the Americans are not the most well- dressed people in the world, they are the most comfortably dressed. Men are seen there with the dreadful chimney-pot hat, but there are very few hatless men ; men wear the shocking swallow-tail coat, but few are to be seen with no coat at all. There is an air of comfort in the appearance of the people which is a marked contrast to that seen in this country, where, too often, people are seen in close contact with rags.

The next thing particularly noticeable is that everybody seems in a hurry to catch a train. This is a state of things which is not favourable to poetry or romance. Had Romeo or Juliet been in a constant state of anxiety about trains, or had their minds been agitated by the question of return-tickets, Shakespeare could not have given us those lovely balcony scenes which are so full of poetry and pathos.

The next thing particularly noticeable is that everybody seems in a hurry to catch a train. This is a state of things which is not favourable to poetry or romance. Had Romeo or Juliet been in a constant state of anxiety about trains, or had their minds been agitated by the question of return-tickets, Shakespeare could not have given us those lovely balcony scenes which are so full of poetry and pathos.

America is the noisiest country that ever existed. One is waked up in the morning, not by the singing of the nightingale, but by the steam whistle.

It is surprising that the sound practical sense of the Americans does not reduce this intolerable noise. All Art depends upon exquisite and delicate sensibility, and such continual turmoil must ultimately be destructive of the musical faculty.

There is not so much beauty to be found in American cities as in Oxford, Cambridge, Salisbury or Winchester, where are lovely relics of a beautiful age ; but still there is a good deal of beauty to be seen in them now and then, but only where the American has not attempted to create it. Where the Americans have attempted to produce beauty they have signally failed. A remarkable characteristic of the Americans is the manner in which they have applied science to modern life.

This is apparent in the most cursory stroll through New York. In England an inventor is regarded almost as a crazy man, and in too many instances invention ends in disappointment and poverty. In America an inventor is honoured, help is forthcoming, and the exercise of ingenuity, the application of science to the work of man, is there the shortest road to wealth. There is no country in the world where machinery is so lovely as in America.

I have always wished to believe that the line of strength and the line of beauty are one. That wish was realised when I contemplated American machinery. It was not until I had seen the water-works at Chicago that I realised the wonders of machinery ; the rise and fall of the steel rods, the symmetrical motion of the great wheels is the most beautifully rhythmic thing I have ever seen.

One is impressed in America, but not favourably impressed, by the inordinate size of everything. The country seems to try to bully one into a belief in its power by its impressive bigness.

I was disappointed with Niagara — most people must be disappointed with Niagara. Every American bride is taken there, and the sight of the stupendous waterfall must be one of the earliest, if not the keenest, disappointments in American married life. One sees it under bad conditions, very far away, the point of view not showing the splendour of the water. To appreciate it really one has to see it from underneath the fall, and to do that it is necessary to be dressed in a yellow oil-skin, which is as ugly as a mackintosh — and I hope none of you ever wears one. It is a consolation to know, however, that such an artist as Madame Bernhardt has not only worn that yellow, ugly dress, but has been photographed in it.

Perhaps the most beautiful part of America is the West, to reach which, however, involves a journey by rail of six days, racing along tied to an ugly tin-kettle of a steam engine. I found but poor consolation for this journey in the fact that the boys who infest the cars and sell everything that one can eat — or should not eat — were selling editions of my poems vilely printed on a kind of grey blotting paper, for the low price of ten cents. Calling these boys on one side I told them that though poets like to be popular they desire to be paid, and selling editions of my poems without giving me a profit is dealing a blow at literature which must have a disastrous effect on poetical aspirants. The invariable reply that they made was that they themselves made a profit out of the transaction and that was all they cared about.

It is a popular superstition that in America a visitor is invariably addressed as “ Stranger. “ I was never once addressed as „Stranger.“ When I went to Texas I was called „Captain“ ; when I got to the centre of the country I was addressed as „Colonel“ and, on arriving at the borders of Mexico, as „General.“ On the whole, however, „Sir,“ the old English method of addressing people is the most common.

It is, perhaps, worth while to note that what many people call Americanisms are really old English expressions which have lingered in our colonies while they have been lost in our own country. Many people imagine that the term “ I guess,“ which is so common in America, is purely an American expression, but it was used by John Locke in his work on „The Understanding,” just as we now use „I think.“

It is in the colonies, and not in the mother country, that the old life of the country really exists. If one wants to realise what English Puritanism is — not at its worst (when it is very bad), but at its best, and then it is not very good — I do not think one can find much of it in England, but much can be found about Boston and Massachusetts. We have got rid of it. America still preserves it, to be, I hope, a short-lived curiosity.

(…) From Salt Lake City one travels over the great plains of Colorado and up the Rocky Mountains, on the top of which is Leadville, the richest city in the world. It has also got the reputation of being the roughest, and every man carries a revolver. I was told that if I went there they would be sure to shoot me or my travelling manager. I wrote and told them that nothing that they could do to my trav- elling manager would intimidate me. They are miners — men working in metals, so I lectured to them on the Ethics of Art. I read them passages from the autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini and they seemed much delighted. I was reproved by my hearers for not having brought him with me.

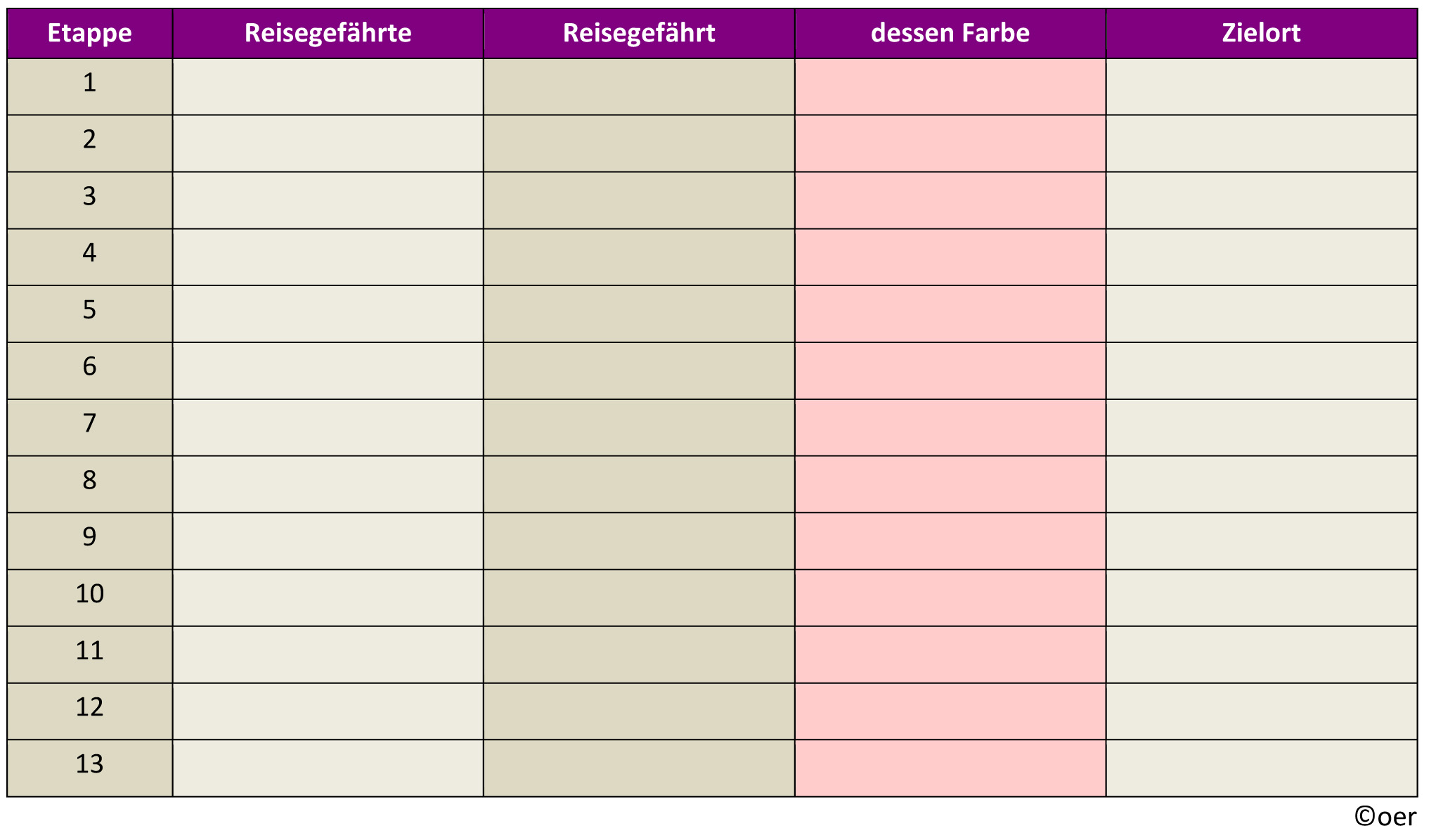

I explained that he had been dead for some little time which elicited the enquiry „Who shot him „? They afterwards took me to a dancing saloon where I saw the only rational method of art criticism I have ever come across. Over the piano was printed a notice:

PLEASE DO NOT SHOOT

THE PIANIST.

HE IS DOING HIS BEST.

The mortality among pianists in that place is marvellous. Then they asked me to supper, and having accepted, I had to descend a mine in a rickety bucket in which it was impossible to be graceful. Having got into the heart of the mountain I had supper, the first course being whisky, the second whisky and the third whisky.

I went to the Theatre to lecture and I was informed that just before I went there two men had been seized for committing a murder, and in that theatre they had been brought on to the stage at eight o’clock in the evening, and then and there tried and executed before a crowded audience. But I found these miners very charming and not at all rough.

Among the more elderly inhabitants of the South I found a melancholy tendency to date every event of importance by the late war. „How beautiful the moon is tonight,“ I once remarked to a gentleman who was standing next to me. „Yes,“ was his reply, „but you should have seen it before the war.“

The Spanish and French have left behind them memorials in the beauty of their names. All the cities that have beautiful names derive them from the Spanish or the French. The English people give intensely ugly names to places. One place had such an ugly name that I refused to lecture there. It was called Grigsville. Supposing I had founded a school of Art there — fancy „Early Grigsville.“ Imagine a School of Art teaching „Grigsville Renaissance.“

As for slang I did not hear much of it, though a young lady who had changed her clothes after an afternoon dance did say that “after the heel kick she shifted her day goods.“

Impressions of America. Edited, with an Introduction by Stuart Mason. Keystone Press, Sunderland 1906. 500 copies, laid paper, all edges uncut, wrappers.