NEW YORK, near America

March 10th, and spring has come at last. On this Thursday, the scrivener’s search for the man he’s wondered about and worried about through the most terrible winter in memory is at a close. Maybe the only place to find him is in caring to know about someone else: a conundrum.

The scrivener has poked around in the usual places where men on the margins are consigned to sanctuary: merciful soup kitchens that ask few questions of their patrons, and the sermonizing sort that dish up the slop after afflicting the hungry with Holy Bible bromides; city shelters, those squalorous incubators of lice and lunacy; a certain untended section under delivery docks at the side of the Salvation Army warehouse; scalps between the horizontal slabs of crumbling schist down in the old commercial rail beds, submerged below the streets of Manhattan’s west side.

Also inspected were venues for a gentleman of forced leisure to while away a non-drinking afternoon: the marbled warrens of the New York Library on Fifth Avenue; the passenger waiting room at Grand Central Station; the Cupcake Café on Ninth Avenue, where America’s last hippies run the establishment and don’t mind the occasional downtrodden customer nursing a coffee for a few hours so long as he behaves.

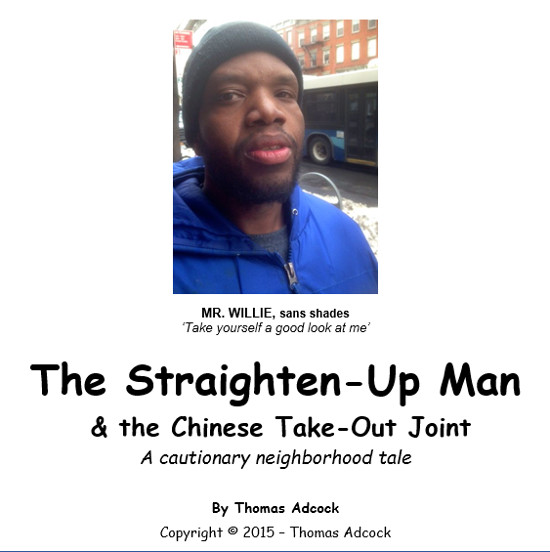

Mr. Willie, as he calls himself, has been elusive since the third week of February. The scrivener thinks back to the night of their first encounter.

*

He walks into the New Panda Chinese restaurant, purveyor of reasonably good take-out fare at pleasant prices. Once a week or so, he legs it around the corner from his building after a hard day’s scrivening to pick up dinner for two.

On this night—December the 4th of last year—he spots someone fresh among the Panda habitués. The new man belongs to a necessitous fraternity, whose brethren are seen (and ignored) throughout Manhattan.

He speaks to no one, the new one. Nor does he buy a meal, or panhandle on the premises. An African American of average size, he’s a brooder. He slumps in a chair next to a trash bin used by the Panda’s handful of eat-in customers, expected to bus their own tables. He keeps his head down, knit cap stretched firmly over his hair and ears, eyes obscured by a pair of round glasses dark enough to shade a Saharan sunrise. What he shows of his face seems to ask, What’s wrong?

Though early in the season, already there have been days when the scrivener is reminded of an elderly nun from his distant youth—Sister Bertice, and her trademark curse for a winter’s day like this one. ’Tis too cold for angels to fly. The scrivener—owner of a well-nourished face as fair as Eire, a closet full of clothes, and a warm apartment—is appropriately scarved, shod, and bundled against Sister’s curse. The brooder wears khaki pants, a gray T-shirt, a blue nylon jacket with attached hood, and sneakers. No socks.

Vagary being the armor of vagabondia, the brooder will eventually reveal his roost as merely “here and there.” On the other hand, the scrivener knows considerable comfort at the top of a brick high-rise—forty-five floors of terraced flats with generous views of the sky above and beyond, the Hudson River below, and the palisades of New Jersey. Many in the scrivener’s neighborhood are impressed by who they are and what they do; the smuggery of a “hot” area, as the realtors call it, is spreading. Patrons of the Panda are of humbler stripe: a clientele quite befitting the simple squat of an orange-canopied shop at sidewalk level of a five-storey tenement crisscrossed in fire escape ladders and situated on a commercial avenue clouded in diesel smog.

Vagary being the armor of vagabondia, the brooder will eventually reveal his roost as merely “here and there.” On the other hand, the scrivener knows considerable comfort at the top of a brick high-rise—forty-five floors of terraced flats with generous views of the sky above and beyond, the Hudson River below, and the palisades of New Jersey. Many in the scrivener’s neighborhood are impressed by who they are and what they do; the smuggery of a “hot” area, as the realtors call it, is spreading. Patrons of the Panda are of humbler stripe: a clientele quite befitting the simple squat of an orange-canopied shop at sidewalk level of a five-storey tenement crisscrossed in fire escape ladders and situated on a commercial avenue clouded in diesel smog.

Customers trudge through the Panda’s doorway from morning ‘til midnight. Inside is the uniform ambience of New York’s dwindling census of divey Chinese take-out joints: tables and chairs of faded pine; scuffed floor, tiled in beige; an aromatic mix of ammonia and monosodium glutamate; fluorescent lighting as harshly shadow-free as an ice cube.

Customers trudge through the Panda’s doorway from morning ‘til midnight. Inside is the uniform ambience of New York’s dwindling census of divey Chinese take-out joints: tables and chairs of faded pine; scuffed floor, tiled in beige; an aromatic mix of ammonia and monosodium glutamate; fluorescent lighting as harshly shadow-free as an ice cube.

Tonight, the scrivener orders sixteen dollars worth of shrimp dumplings and General Tso’s chicken, which he will share with his pretty wife. Dinner à deux by the light of a Netflix movie streamed over big-screen, high-def TV.

He pays his tab, the scrivener does, and heads for the door. But he pauses before stepping out to the snow and the dark, and into a nasty wind blowing off the river. He looks back to the slumped brooder, and says to himself, Really—I must speak to this man. He decides this owing to his mood, which is curious—

How curious it is that Manhattan never fails to match the scrivener’s palette of moods. When he’s in a hurry, so is everyone else, even the pigeons; when nostalgic, the streets are albums of black-and-white snapshots from back in the day; when pensive, the city ruckus has a way of forcing him to consider issues more important than his own comforts, or sorrows.

—“Could you use a dollar?” the scrivener asks. He places a bill on the brooder’s knee.

The money lies undisturbed for long moment. The brooder finally pockets the offertory, and raises his head. His expression is unsurprised, as if he’s anticipated a donation from this particular fair-faced stranger; as if he’s been observing his observer. The scrivener notices a trim goatee beneath the dark glasses.

“Can’t we all,” says the brooder. Then, after a beat, “Your dinner smells fine.”

His voice is clear, his tone sociable. There is no trace of catarrh that comes of sleeping in windswept doorways, no bummy rank to body or garb, no quintessential whiff of muscatel. Life on the streets is a recent circumstance, the scrivener posits.

The brooder drops his head back into its hiding place. The scrivener thinks of ostriches at the zoo. He decides to linger, for he has stumbled upon the writer’s catnip, which is to say irony. Here before the scrivener is a man of Gotham’s bleak edges; a hungry man—probably hungry—yet a man of reserve: uncomplaining, rather dignified. Here before the scrivener is a fallen man—probably fallen. A man obliged to accept a cheap donation, yet a man of nuanced swagger. Here—a hungry man who shelters from the cold in a restaurant, of all places.

“My name is Tom,” says the curious scrivener. He places a hand on the brooder’s shoulder, and asks, “Yours?”

Up bobs a capped head. “What’s wrong?” the brooder actually says. “Don’t you got friends? Don’t you got a home for that fine dinner?”

“Sure I have friends.”

“That’s nice. Where’s home?”

“Nearby.” Vagary likewise protects the affluent, and those—like the scrivener—who seem so. “How about you?”

“Here and there.” The brooder shrugs. “You know. Here and there.“

“Mind if I ask your name again?”

“Don’t see how it hurts. Willie. You call me Mr. Willie.”

The brooder taps his feet on the scuffed floor. His bare ankles are numb from chill drafts that whoosh around when a customer uses the door. Numb, the scrivener notes, but not yet swollen to unsightliness.

“Whyn’t you go home.” The brooder does not mean this as a question.

“All right, Mr. Willie. See you around.”

“I suppose.”

The abstruse exchange is ended. Best to leave it that way, the scrivener decides. Still, he makes no immediate move for the door.

“We can’t be talking here,” Mr. Willie decides to say. “It’s my place of business. I’m the straighten-up man.”

The brooder reads a scribble of confusion on his donor’s face. “End of the night, see, I straighten up,” he explains. “It’s how I get a fine dinner of my own.”

Mr. Willie risks a glance at his employer, a no-nonsense Chinese woman who minds the till. He whispers to the scrivener, “You want, we can talk in the street sometime. I don’t mind.”

*

That very morning’s “Styles” section of New York Times—a misnomered department of reportage on fashions for the beau monde of shimmering Manhattan, published by the newspaper located one block east of the Panda—provided the scrivener his usual Thursday amusement. As well, the wincing memory of a purple run of his own prose: Manhattan is a jagged heart that pumps a bloody ooze of contrast through the undulating body of an ugly-beautiful city. Once upon a time, the scrivener was given to overwrought metaphor of this sort; in those days, he considered the city’s incongruous nature as brutally romantic. Now well into his autumn days, he recognizes the jagged heart of New York for what it is: a burlesque of allure.

That very morning’s “Styles” section of New York Times—a misnomered department of reportage on fashions for the beau monde of shimmering Manhattan, published by the newspaper located one block east of the Panda—provided the scrivener his usual Thursday amusement. As well, the wincing memory of a purple run of his own prose: Manhattan is a jagged heart that pumps a bloody ooze of contrast through the undulating body of an ugly-beautiful city. Once upon a time, the scrivener was given to overwrought metaphor of this sort; in those days, he considered the city’s incongruous nature as brutally romantic. Now well into his autumn days, he recognizes the jagged heart of New York for what it is: a burlesque of allure.

Included in the smuggery of “Styles” that morning was an article about the shabby-chic wardrobes of young adults whose dietary staples are tofu, kale, and gluten-free croissants. The scrivener was especially struck by a passage about pre-ripped blue jeans and other such accoutrements of youngsters with carefully tousled hair, stubbled chins, and rumpled garments as their chimera of comradeship with the proletariat:

Streetwear beggars definition as a category but tends to encompass under its umbrella much of what is young [and] comfortable …[A]s it establishes itself as a force in fashion with a shelf life beyond simple trend, a question floats to the fore: What happens to streetwear when it grows up?

Indeed, whence do dungarees mature? The scrivener suspects that “streetwear” showcased in boutiques known for startling price tags winds up as second-hand shmata at thrift shops and church rummage sales. His suspicion is based on personal consumer experience, though he would never succumb to preciously molested denim.

Certainly the likes of Mr. Willie have little desire for holes in their pants.

*

Three weeks later. Morning.

Having purchased the newspapers, the scrivener bumps into Mr. Willie outside a Starbucks on his way home. Mr. Willie was lounged on an iced-over fire department standpipe, as if anticipating this very bump; as if knowing his observer’s routine. The scrivener extends an invitation.

“Yeah, all right,” says Mr. Willie. “They got coffee for sure, but also the cold eyes. Which you going to see how they look at me if you take me in.”

“Let’s go,” says the scrivener.

“You don’t mind, I don’t mind.”

“Grande for two,” the scrivener tells a barista, who is suddenly not so cheerful. She doesn’t care for the sight of big dark glasses on a suspicious individual of dark complexion. The scrivener asks Mr. Willie, “How do you take it?”

“Cold eyes, not so good. Coffee, light and plenty sweet.”

The odd couple moves to a counter arrayed in serve-yourself additives that range from skimmed milk to lactose-free. Mr. Willie chooses cream and a fistful of raw sugar packets, several of which he pockets.

Messrs. Tom and Willie find a table. “Please don’t take offense at my curiosity,” says the scrivener, “but what do you do with your days?”

“Read the papers, like you,” says the brooder. “Only I don’t buy them like you. Don’t have to. People leave them in the trash.”

He adds, as if wanting to get this off his chest: “Curiosity ain’t offensive. Neglect is, disrespect is. You know what? You’re about the only white man I know ever take a care to talk to me without looking like you want to go puke.”

Messrs. Tom and Willie complain about the lousy weather for a long time because their discussion seems veering toward “dread emotional talk,” as the scrivener’s Irish grandfather would say—a category of conversation that scares the bejesus out of most men. The scrivener holds back on expressing concern about Mr. Willie’s lack of suitable clothes for lousy weather; he imagines this could cause embarrassment.

“I like reading about economics,” says Mr. Willie, broaching a topic seemingly as neutral as weather or sports or automobiles. “That a surprise to you?”

“Not necessarily.”

“I study on politics, too,” says Mr. Willie. “The other day, I come across a great true line: ‘In the Soviet Union, capitalism triumphed over communism. In America, capitalism triumphed over democracy.’”

“Yes, I’ve read that. It’s an epigram by Fran Lebowitz,” says the scrivener of a fellow scrivener. “She’s a great satirist. She was kicked out of high school—“

“Me, too!” Mr. Willie interrupts.

—“For years, she’s been working on a novel called Exterior Signs of Wealth.”

“What’s it about?”

“Rich people who want to be artists, and artists who want to be rich.”

“Interesting,” says Mr. Willie, rising abruptly from the table. “Well, I got to go now. Thanks for the coffee.”

That would be all for today.

As irony would have it, tonight the scrivener would attend an exhibition at an art gallery across the East River from Manhattan—in a woebegone section of Brooklyn undergoing gentrification by moneyed young suburban escapees busily establishing the ghetto of their dreams.

The scrivener would find himself utterly baffled by a certain display. Surely, Ms. Lebowitz would be amused by the artist’s description—neatly typed on an index card to the side of whatever-it-was:

My work is an investigation in pre-apperception, where everything is an extension of the same entity, equalized in a constant state of present. Whether two dimensions or three, the goal is to create an empathetic composition where the players participate and understand rather than simply coincide.

Later, back home, the scrivener would think of Mr. Willie while reading an article in the online Common Dreams magazine about a plutocratic gathering in the ancient posh of a London castle. Author Gary Olson, chairman of the political science department at Moravian College in Pennsylvania, wrote of two hundred and fifty “titans of finance and business” in attendance—representing €28 trillion in assets, or “fully one-third of the world’s total investable assets.”

Lady Lynn Foester de Rothschild, she of the Rothschild banking dynasty, hosted the swarm of magnates. Professor Olson quoted from her welcoming remarks: “It is really dangerous for business when business is viewed as one of society’s problems,” said Lady R. “And that is where we are today.”

The professor quoted two other tycoon-attendees. One worried about the “capitalist threat to capitalism.” The other fretted about “a very real danger that politicians could seek to remedy the situation by legislating capitalism out of business.”

*

Through January and into the third week of February, Messrs. Tom and Willie met a total of four times: three at the Panda, once again at the Starbucks. As on other occasions, Mr. Willie was parsimonious with biographical markers, and elected to close each session bluntly. The scrivener accepted these conditions (impatiently at first), on the assumption that Mr. Willie employed circumspection as a guarantee of perpetuating a conversation he enjoyed—probably enjoyed.

And so, the scrivener knows of Mr. Willie’s mysterious life only that which Mr. Willie has self-disclosed: he was expelled from a New Jersey high school for selling marijuana on campus; when his mother died (cause unmentioned), he lit off to Manhattan with thoughts of swinging on a star (by way of a talent unmentioned); ugliness (of a type unmentioned) at a series of dead end jobs somehow led to a string of lock-ups at Rikers Island Correctional Facility; he wrestled, ferociously, with botanicals and Mr. Johnnie Walker and is now petrified of both; he keeps a locker at the city-run recreation center on West 25th Street, where he bathes and launders his clothes, and is careful not to be conspicuous by hanging around the place; the kind of woman he desires has no interest in a zero-man (his term).

Pressed for detail, even the most innocuous, has resulted in Mr. Willie snapping at his observer, “That’s off the record!”

Did sense he was being recorded?

*

The twentieth of February. Friday.

Sunlight softens this time of year, inspiring hopes of a winter thaw and memories of outdoor warmth. Though customarily sunny this morning, bitterly cold air still stings the nose, inside and out. The scrivener is huffing down Ninth Avenue to the neighborhood grocery. Passing by the Cupcake Café, he catches sight of an elderly woman inside, seated at a window table, wrapped in a balding fur coat. Her, and someone else: at a table adjacent to the interesting-looking old lady is Mr. Willie in his dark glasses, waving for the curious scrivener to come join him.

“You seen the bad-news sign over to the Panda?” Mr. Willie asks.

“You seen the bad-news sign over to the Panda?” Mr. Willie asks.

No.

“Well, I guess that’s that,” Mr. Willie says. His hands are wrapped around a mug of steaming coffee, but they don’t look warm. “Landlord wants bigger rent, I expect. It’s always the way.”

Again, the scrivener flashes on his Irish grandfather, who enjoyed expressing himself on the subject of landlords: They ain’t the lords of the land, they’re the scum of the earth. He shares this sentiment with Mr. Willie.

“Oh, that’s good,” says Mr. Willie. “You best watch out for the lords yourself. That fine place where you live—“

The scrivener is surprised that Mr. Willie knows his building. But after all, he’d observed his observer before, hadn’t he?

“—It’s got the lords, too. They got cold hearts and cold eyes. All they know is counting up numbers. Hope you don’t get put out like the Chinese got put out.”

The elderly woman departs.

Mr. Willie stands up and says, “Well, I got to go, too.”

The scrivener, imagining he might never see him again, follows Mr. Willie out the door to the frozen avenue.

“What do you look like without the shades?” the scrivener asks.

Mr. Willie removes his goggles. “Take yourself a good look at me,” he says.

The scrivener dips into his coat pocket for his trusty smart-phone.

“Five bucks for a picture,” says Mr. Willie.

Transaction complete, Mr. Willie walks away.

Other pedestrians totter along on the ice crust. They are on various neighborhood missions, silently brooding over their own mysterious battles. A mist formed in the air. Yet another snowfall is coming. A lump of slush breaks free from somewhere over the café, plopping to the sidewalk.

The scrivener decides to keep an eye out for the interesting-looking old lady with the balding fur coat.

Thomas Adcock

Thomas Adcock is America correspondent for CulturMag.

Im Februar 2015 erscheint seine Erzählung “The Cannibal of Pang Yang” als eBook bei CulturBooks. Zur Vorschau.