Heute denkt Christopher G. Moore darüber nach, dass auch Kriminelle gefälligst darauf zu achten haben, wer sie zum Teufel sind. Hier geht es zu den bisherigen Teilen …

Heute denkt Christopher G. Moore darüber nach, dass auch Kriminelle gefälligst darauf zu achten haben, wer sie zum Teufel sind. Hier geht es zu den bisherigen Teilen …

Status and Crime

According to the BBC, a bottle of 1811 Chateau d’Yquem was bought for 75,000 pounds sterling by French collector Christian Vanneque. Depending on your point of view that kind of expenditure is either highly disturbing or makes you secretly envious, wishing you had that kind of money.

A few years ago, the Boston Globe ran a story about the average worldwide income which was pegged at $7,000 a year. It would take the average worker 17.6 years if he or she saved every last cent to buy that bottle.

A few years ago, the Boston Globe ran a story about the average worldwide income which was pegged at $7,000 a year. It would take the average worker 17.6 years if he or she saved every last cent to buy that bottle.

This isn’t a rant against the rich and how they spend their money. It is an essay about how deep desire for status, recognition and approval. And how these desires are partly responsible for the economic reality of our time—1% of Americans own 40% of the wealth and 20% of the income. It also an essay about the efforts people go about in using money to gain status and recognition in the global community. Pay that kind of money for a bottle of wine and people around the world will read about you, they will know your name, the name of your restaurant. As a marketing ploy, it is quite brilliant. That bottle of wine also highlights how all that wealth which is supposed to go into creating new jobs, is just as likely to find new and novel ways to display status.

Criminals are a diverse lot with manifest motives and intentions. The criminal class includes the eleven year old who steals a loaf of bread because he’s hungry. Hunger doesn’t exclude him from being a criminal. In the 18th century, he might be transported to Australia. We tend to have sympathy for criminals driven by necessity.

The man driving his mother whose has had a stroke at high speed to a hospital, runs red lights, hits a couple of parked cars, but manages to get her to the hospital before she dies is also a law-breaker but we have a different feeling about the ‘culpability’ issue than say a teenager who gets drunk and does all the same things as the man going to the hospital. Yet we have no problem thinking the teenager should be punished and taught a lesson.

Necessity drives certain impulses that lead to criminal behavior. In an emotional rage, someone gets out of their car and stabs another motorist to death. Or someone kills their spouse, neighbor, friend over a remark, insult, or slight. That is, someone has questioned their ‘status’ and that activity is always dangerous. In a face culture like Thailand, where status is of paramount importance, slights to status invite retaliation.

Necessity drives certain impulses that lead to criminal behavior. In an emotional rage, someone gets out of their car and stabs another motorist to death. Or someone kills their spouse, neighbor, friend over a remark, insult, or slight. That is, someone has questioned their ‘status’ and that activity is always dangerous. In a face culture like Thailand, where status is of paramount importance, slights to status invite retaliation.

We want status. Perhaps it is a need like food, water, shelter and sex. Status motives people. Give them a ribbon, decoration, trophy, or gold star and they will fight and die for you. Competition for status makes short cuts tempting. And short cuts are the slippery slope to criminal activity. When thinking what drives someone to commit a crime, examine the underlying impulse that was the motive for crime. Was the conduct done because the criminal is starving or his mother is dying, or will the result of the crime evaluate his or her status?

I steal a loaf of bread because I am hungry isn’t the same as I steal a Rolex not because I want to tell the time but because I want to impress my friends. Or I invite a government official to dinner and pop open a bottle of wine that cost 75,000 pounds sterling before asking them to grant me a telecom, mining, or shipping concession.

Criminal law fences off status acquiring activity as well as actions to acquire goods owned by others without paying for them. Prisons are filled with criminals who failed in their quest to gain status through illegal means. And they bunk with those whose illegally acquired goods, also mainly to achieve status, failed.

The large crimes needed to pull off big time; international status takes us into the realm of banking, finance and journalism. If you can elevate your status sufficiently high, you can influence the police, courts and government that your activity is socially useful and not criminal. You can support changes to laws and regulations that would block your ambitions to increase your status even more. Hedge fund managers, CEOs, bankers have leveraged their status by organizing politically and reducing any attempts to control their behavior or to tax their gains.

Of course, these status seekers know that others are unhappy with the lopsided way that status is assigned to them. They also know that by cooking the books, they can stay ‘legal’ while the vast majority of the population struggle for the scraps of status and may find their activity ‘criminalized’. The protected class, which has most of the status horde, is quite happy to imprison the status seekers below. It teaches them a lesson about life. Status seeking as a goal is limited to a tiny number of winners. Once they enter the winner’s circle, they are content to lock the door.

Criminal law is what we use to control the losers in the status race. The winners pay governments to write that laws to constrain the activities of the also-rans. The fundamental problem, as the current budget crisis in the United States suggests, is that unless governments control status seekers in the top 1% of the population, that class will own them, control them, and ensure that the prisons are filled by those who fail to play by the rules as defined by them.

We want our star football players, singers, actors and Nobel Prize winners. The problem are these winners are used as a beard by those with predator business talents that enrich without corresponding benefits to the larger community. Hedge fund managers, finance moguls and CEOs of the Fortune 500 companies (who make up the bulk of the .01%) of top income earners aren’t rock stars nor are they coming up with a cure for cancer. But they have the skill to skate close to the boundaries of the laws, rules and regulations that govern their activities, sometimes skating over the line; and if they can, fund a politician to extend the line.

This group redefines what is a crime in order to better pursue their personal interest.

When those outside of government achieve status above those elected to government, and those in government owe their position to the wealthiest citizens, the laws no longer reflect the majority of citizens. And the majority of citizens no longer understand that their view and opinions have been shaped and distributed by those who wish to use them for their own ends.

Redistribution of wealth is one way to combat status hoarding. But redistribution is a loaded, nasty taboo word. So let’s think of this concentration of wealth like the pollution that poisons the atmosphere and contributes to climate change; let’s not redistribute wealth or income. Let’s talk about “cap”. This is something we are familiar with. There’s a cap on the speed limit. You can’t go as fast as you want. There’s a cap on the chemical and toxics you can dump into rivers, lakes, canals and the ocean. There are caps on carbon emissions. The one common feature that caps have: is they don’t redistribute speed, chemicals or carbon, but they do place a limit on making a profit from driving at high speeds (truck drivers) or from polluting the air, rivers, forests and oceans. We have no problem saying the community-interest overrides the self-interest. Society already agrees to criminalize certain selfish behavior committed by individuals even though it may deprive them of more income or wealth.

Redistribution of wealth is one way to combat status hoarding. But redistribution is a loaded, nasty taboo word. So let’s think of this concentration of wealth like the pollution that poisons the atmosphere and contributes to climate change; let’s not redistribute wealth or income. Let’s talk about “cap”. This is something we are familiar with. There’s a cap on the speed limit. You can’t go as fast as you want. There’s a cap on the chemical and toxics you can dump into rivers, lakes, canals and the ocean. There are caps on carbon emissions. The one common feature that caps have: is they don’t redistribute speed, chemicals or carbon, but they do place a limit on making a profit from driving at high speeds (truck drivers) or from polluting the air, rivers, forests and oceans. We have no problem saying the community-interest overrides the self-interest. Society already agrees to criminalize certain selfish behavior committed by individuals even though it may deprive them of more income or wealth.

Why not put a ‘cap’ on income and wealth? And for the same basic reason, that a concentration of a large percentage of the wealth in the upper one percent is detrimental to the rest of the community and damages them. Anyone who doesn’t believe that such damage doesn’t spread across a large range of other people’s interest haven’t been watching the James and Rupert Murdock show on the BBC. Or have already forgot about the financial crash of 2008. Say cap income at the current rates the rich pay on the first $12 million dollars a year. Most people could scrap past on a million a month. Then start progressive taxing the additional income until it hits $24 million a year and then let the tax be 90%. On wealth, the first $250 million, old rules apply, after that it goes back to the community. Even if the community doesn’t need it; the money should go back. There is a good policy reason: income and wealth concentrations at the current levels in the United States threat the fabric of representative democracy, and the policing and judicial system.

If we are honest, the arguments for unlimited wealth and income concentration are about keeping people moving ahead with incentives. The reality is what moves people to continue to excel and push the boundaries is they want recognition. More than want it; they crave recognition and to show a higher status. Our problem is “globalization is big money” has become universal status measuring stick. The consensus we once had that allowed for share meaning and structure has fractured into cult-like enclaves where debate, reason and dialogue no longer are welcome.

If we are honest, the arguments for unlimited wealth and income concentration are about keeping people moving ahead with incentives. The reality is what moves people to continue to excel and push the boundaries is they want recognition. More than want it; they crave recognition and to show a higher status. Our problem is “globalization is big money” has become universal status measuring stick. The consensus we once had that allowed for share meaning and structure has fractured into cult-like enclaves where debate, reason and dialogue no longer are welcome.

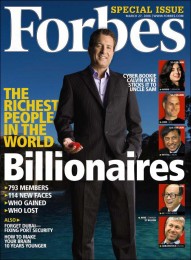

The Forbes list of the richest people is translated, read, studied and talked about in every language on the planet. If we could find new status measuring sticks then money would matter less. Those who hunger for our community (and more importantly their peer’s) recognition can have airports, squares, and parks named after them; give them awards, medals, citations, knighthoods, and gold bars to wear on their lapels. Revise the Forbes annual list to include the number of gold stars, red ribbons, or public declarations by MPs as to their worthy contributions.

The Forbes list of the richest people is translated, read, studied and talked about in every language on the planet. If we could find new status measuring sticks then money would matter less. Those who hunger for our community (and more importantly their peer’s) recognition can have airports, squares, and parks named after them; give them awards, medals, citations, knighthoods, and gold bars to wear on their lapels. Revise the Forbes annual list to include the number of gold stars, red ribbons, or public declarations by MPs as to their worthy contributions.

We are at a crossroads politically, socially and economically in finding the political will to win this battle. Unless we dismantle the unregulated status consolidation at the top, the democratic system will collapse into warring cults and when that happens the scramble to maintain order will overwhelm even the best of legal systems. Let people strive for status. But let it be known that there are limits as to how much status any society can reasonably allow to fall into a few hands.

And let’s recognize that without caps on pollution and income the whole ecosystem is threatened. The rebalancing of community interest with self-interest has never been easy; and it is a kind of work that never is finished. All we can say looking around us is that self-interested income generation and wealth is no longer remotely in equilibrium with the larger community interest.

(Quelle: http://www.extravaganzi.com/1811-chateau-d%E2%80%99yquem-the-worlds-most-expensive-bottle-of-white-wine/)

As for those who open that bottle 1811 Chateau d’Yquem and pass it around, they might want to think about how far we’ve come in the last 200 years. And ask themselves who will be buying a bottle of 2011 Chateau d’Yquem in 2211. And at what price and what will their world look like?

Give some thought to that nice gold star. Say one star for every $15 million in tax paid. Wouldn’t that invite envy from friends and colleagues, the attention of beautiful women, the admiration of civil society? I know what you are thinking. I can get one of those gold stars for a 100 baht on Khao San Road. Maybe. But it will still be difficult to pull off the counterfeit billionaire trick at the guesthouse.

Dieser Text ist am 29. Juli 2011 auch auf unserer Partner-Seite erschienen.

„Der Untreue-Index“ beim Unionsverlag.

Bangkok Noir. The Cultural Detective. Kindle/Amazon. UK and Kindle/Amazon.USA. His lastest Vincent Calvino novel, 12th in the series, is titled 9 Gold Bullets and is available as an ebook on Kindle. Moores Podcast. Die Vincent Calvino-Romane. Der Autor beim Unionsverlag hier. Zu Christopher G. Moores Website.