Geld. Wir benutzen es jeden Tag – manche spielen mit großen Summen aus der Portokasse, während für andere jedes Stück Hartgeld zählt. Heute erzählt Christopher G. Moore ein kleines Musterbeispiel zu dem berühmten und immer wieder interessanten Thema, wo das Geld eigentlich ist, das weg ist. Weg oder woanders.

Geld. Wir benutzen es jeden Tag – manche spielen mit großen Summen aus der Portokasse, während für andere jedes Stück Hartgeld zählt. Heute erzählt Christopher G. Moore ein kleines Musterbeispiel zu dem berühmten und immer wieder interessanten Thema, wo das Geld eigentlich ist, das weg ist. Weg oder woanders.

That’s Where the Money Is

That’s Where the Money Is

When Willie Sutton, the American bank robber, was asked why he robbed banks, he replied, “That’s where the money is.” Brooklyn born Slick Willie was on to something. The economic aspect of crime is vastly underrated. Extending Carl von Clausewitz’s war is politics by other means we glimpse the reality that crime is business by other means. We begin to understand the similar impulse between those who rob banks and investment bankers selling hedge funds stuffed with worthless mortgages.

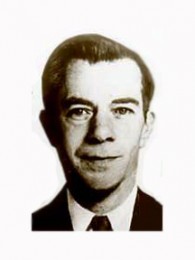

Willie Sutton

If Willie Sutton were alive today, he might rethink his assumption that banks are where the money is. At least in places like Thailand. Not that there aren’t many banks stuffed with cash. There are. The money is in vaults and hard to get into. And with Bangkok traffic, once the heist is done, getting away is also a challenge. Besides, the big money isn’t in banks. It’s kept inside houses of the class of people who must report their holdings, cash, money, jewels and so on. These people are politicians, senior civil servants, military and police big shots. The idea is to prevent the people at the center of power from profiting from their official position.

Transparency International ranks Thailand #78 on the Corruption Perception Index for 2010– squeezed between Serbia and Malawi.

What do corrupt officials do with their cash? If there is a huge amount, it is difficult to spend without attracting attention. Not to mention that a new villa or an airplane has to be reported on the list of assets and the money for it must be accounted for.

They could bank it. But then there is a paper trail and they have to report it in Thailand, and someone might raise an eyebrow over the odd ten million dollar deposit by an official who on paper makes about $2,000 a month. Or the official might put the money in the name of his maid or driver, a best friend or distant kin. All of those alternatives have their own set of risk. Mainly a maid with ten million in an offshore account might ask for a raise or two.

The other alternative is to bag the cash, and keep it at home. That’s a safe place, right? The problem is a lot of cash takes a lot of room. It can fill an entire room.

Servants working in such a house notice these things. Open a door to a room and find wall to wall stacks of bank notes makes dusting a delight. You wouldn’t want another job. In fact you might brag to your friends. And may be some of your friends know people who are criminals and before you know someone is planning a heist.

A man’s home is his castle by English tradition. As far as I’ve been able to determine English tradition is little followed in this part of the world. But a recent case involving a senior civil servant, suggests that for some Thais home banking has an entirely new meaning.

The permanent secretary at the Transport Ministry Mr. Supoj Saplom, who also serves on the board of directors of Thai Airways International and Mass Rapid Transit Authority, has found himself in the public limelight. On the evening of 12th November, robbers rolled up to his house while he and his wife were away.

The crew of robbers apparently forced their way inside and made off with cash. Here’s where things get interesting. Mr. Supoj apparently talked with the police and reported the robbery once he arrived back home to find his maid tied up. He had little choice as his maid spilled the bean to the cops as the house was broken in. It’s likely that Supoj must have called the police to downplay the cash amount. His wife also asked to the media not to make a big fuss about the heist.

The senior civil servant initially told the police the robbers had made off with one million baht. There are unconfirmed reports (that hasn’t stop the local press from reporting them or me from blogging about them), that he phoned back and said, it was three million baht and finally called again saying it was five million baht that had been lost. You have this vision of a man trying to estimate what was taken and finding it hard to come up with a firm number.

Since this is an important VIP the police immediately set out after the thieves. The CCTV camera had caught their images (though they were disguised) and their vehicle. Soon enough the first couple of robbers were arrested. People who steal from VIPs almost always get caught, and it makes you wonder why they continue to defy such odds. Clearly these guys were in a different class from Willie Sutton who would have evaded police for at least another 48 hours.

The Thai robbers had there own version of how much cash they stole ranging from 9 million to 200 million baht. To make it really interesting one of the robbers said they hadn’t made much of a dent in the bags of cash they found. The robbers estimated there was between 700 million to one billion baht in cash inside the house. What it comes down to is no one is sure how much the robbers stole,whether the amount recover by the cops is all or just part of what they stole, or how much cash was in the house.

A couple of days ago a Thai language newspaper reported that16 million was recovered and the police confirmed at least 100 million was stolen. On Thursday 24th November, the Bangkok Post said the robbers ran off with at least 50 million baht. One heads swims with large numbers. It may be that the robbers, cops and Supoj haven’t yet found out the exact scope of the robbery, who was behind the heist and how much loot was left behind.

Cases like this one raise enough questions to keep film makers, pundits, novelists, scholars, bankers, political scientists, security operations personnel, prosecutors, investigators, independent agencies and politicians in business for years. Mr. Supoj has been transferred to an inactive position in the Prime Minister’s Office (it’s confusing, I know, but trust me this is where most of these cases end).

The lesson from the Supoj caper won’t be lost on a globalized world of criminals. Forget about what Willie Sutton taught all those years before. Get a copy of the latest Transparency International Index Report, find a country with nice beaches, good climate that is reasonably corrupt. Get a list of the senior politicians and civil servants. Figure out the lay out of their luxury villas. Search on Google maps for the ones with little or no security. That means a stakeout. Locate the surveillance cameras, know how to disable them without letting those who watch them know they’ve been tampered with. Wait until the boss and his family are away for a wedding, funeral or holiday, disable the cameras and other security devices, tie up the maid and steal the cash. Chances are the victim won’t make Mr. Supoj’s mistake and call the police. They can see that approach is bound to backfire. But it would be a good idea to get out of the country as soon as possible.

Perhaps the only way to combat corruption is to give the modern day Willie Suttons a green light to strip away the ill-gotten gains of the corrupt. Let the bank robbers clean up government by cleaning out the corrupt. At least with crooks like Willie Sutton you have an admirable degree of honesty as to what they do and why they do it.

Police interrogation of the initial set of robbers indicated they had been carefully planning the heist. They had rented a nearby apartment and went on stakeout. They said, Mr. Supoj was “unusually rich,” so he must have taken it “from the people.” But they were more Willie Suttons than Robin Hoods, as their is no evidence they were handing out cash to the poor.

There are thieves and then there are thieves and sometimes it is difficult to tell the good guys from the bad one. In this neck of the global woods, honestly rarely extends to the class of politicians and civil servants gorging at the expense of the public.

We can kill two birds with one stone. We make it much more dangerous to be corrupt and we allow professional thieves to retire and leave the rest of us alone. Of course, the corrupt won’t take this lightly. I’d recommend buying shares in international security agencies that advise the ultra rich how to protect themselves, property and cash from the likes of the Willie Suttons of the world. In that case, you as a shareholder make off with the cash that a wannabe Willies would otherwise take.

Christopher G. Moore

Dieser Text erschien am 25.11. 2011 auf unserer Partner-Seite.

Der Untreue-Index beim Unionsverlag. Bangkok Noir. The Cultural Detective. Kindle/Amazon. UK and Kindle/Amazon USA.

His latest Vincent Calvino novel, 12th in the series, is titled 9 Gold Bullets and is available as an ebook on Kindle.

Moores Podcast. Die Vincent Calvino-Romane. Der Autor beim Unionsverlag hier. Zu Christopher G. Moores Website und zu Tobias Gohlis’ Rezension des Untreue Index bei arte.tv