Christopher G. Moore war auf Reisen. Und in Buenos Aires, dieser durch und durch literarischen Stadt, fiel ihm auf, dass etwas zu fehlen schien. Ironie …

Christopher G. Moore war auf Reisen. Und in Buenos Aires, dieser durch und durch literarischen Stadt, fiel ihm auf, dass etwas zu fehlen schien. Ironie …

The Death of Literary Irony

Irony has been the stock and trade of novelists through the ages. George Orwell’s The Hanging is a perfect example of dramatic irony. We follow a condemned Burmese man on his way to the gallows as he carefully sidestepping the puddle of water along the path so as not to dirty his shoes. Or Shooting an Elephant we witness the torment of a British colonial official in Burma who is torn between allowing an elephant to live and lose his authority over assembled villagers and shooting an elephant as a way of reinforcing his power. This is an example of situational irony.

Irony is that lovely, moving, touching human situation where the best of our writers present us with incongruity or a conflict that transcends the behavior, thoughts, words or desires of the character. Irony has been labeled as a rhetorical device or literary technique.

As a short hand wiki definition that is good as far as it goes, but irony is something else. It is subversive, it is a both an invitation to a kind of bonding that comes from recognizing the disturbing contradictions that thrust themselves into a characters life and it is also a shock or surprise as we deliberate about the meaning of life written in evoked in a larger frame that we expected. We wide angle the context of the scene or situation and irony is our lens.

We’ve entered, or will soon do so, an era where literary irony which operated a cartel on irony has been exhausted. Literary irony for most purposes is dead. Not buried, but dead. The zombies continue to haunt the pages of our novelists, thrusting a goulish finger at what passes for a condemned man’s puddle jump and we look, we stare and then we shrug and turn the page. Literary Irony is quaint, dated, and old fashioned. We are longer impressed or surprised. We don’t feel the same degree of intimacy as our parents and grandparents felt reading an ironic passage.

My theory is our present information world has been hyper-inflated with incongruity and conflict. Large data dump that pass our eyes daily from politics to culture and economics; the default for communicating discontent is to use irony. From Jay Leno to the Daily Show, TV has colonized irony like termites in a wood palace. Switching metaphors, the smoking gun of irony is found at the scene of just about any blog you read, Twitter feed is littered with irony, Facebook is an open sea of irony, obit piece are dipped in it, TV commercials sell you stuff based on irony, and lyrics have put it to music.

We suffer from a massive irony overload. It’s not that irony no longer moves us as in the past, our lives are now lived as if incongruity, the heart and soul of irony, is our normal, expected, and demanded psychological state. Like an old married couple sitting across the dinner table attending to their iPad with half a dozen windows feeding irony fix as they work their knives and forks in an oddly synchronized fashion. They call this the modern family meal—and without irony. Our sense of incongruity has been blunted like a sword struck too many times against a large rock. It is even useless to fall on.

How did I come to this conclusion that we no longer respond to ironic dramas and situations in the same way as Orwell’s time? It happened during a visit to a cemetery in Buenos Aries. Prisons, cemeteries, courtrooms, universities and slums are a good place to judge the place of irony in a culture.

The day before my trip down the rows of the dead, I’d been taken by car out to La Plata University where I was scheduled to give a talk about cross-cultural issues in my writing. My task was to address a class of about 40 English majors who were studying to become translators. These were the kind of young people who had a professional stake in irony.

On this journey, the car passed through the outskirts of Buenos Aries. We passed kilometers of slums—hard-scrabbled squalid hovels bearing witness to heart-wrenching suffering, poverty and desperation. It was hard to believe that human being could inhabit such awful conditions and not revolt. The students were attentive and asked many questions about Thailand, literature and culture. In the corridors students made protest banners. They seemed politically engaged in a way that Thai university students were not. These were large state universities and didn’t cater to the offspring of the ultra rich.

The next day, my gang of four Latin American authors (we were attending Buenos Aries Noir, a conference organized by Ernesto Mello) and I set off to visit La Recoleta Cemetery. This sprawling 14 acres in the heart of in Buenos Aires contained 4691 vaults. Mausoleums grand and small housed the remains of generals, presidents, with a dusting of poets and actors. Their final vaults inspired by Art Deco, Art Nouveau, Baroque and Neo-Gothic created a city of the dead unlike any place I’d seen.

The contrast between the slums along the road from Buenos Aries to La Plata which housed the living and the Art Deco mausoleums made from fine marble was like watching a thousand condemned men do a tango around a puddle on their way to be hanged. The celebration of the powerful in death transcends humanity offered to the living. I watched as people came to bring flowers and take photographs of Eva Peron’s mausoleum. Eva Peron was a perfect example of a patron who entered the grand station of national politics on the side of the poor. In death, she wasn’t buried with those she sought to represent and encourage.

The contrast between the slums along the road from Buenos Aries to La Plata which housed the living and the Art Deco mausoleums made from fine marble was like watching a thousand condemned men do a tango around a puddle on their way to be hanged. The celebration of the powerful in death transcends humanity offered to the living. I watched as people came to bring flowers and take photographs of Eva Peron’s mausoleum. Eva Peron was a perfect example of a patron who entered the grand station of national politics on the side of the poor. In death, she wasn’t buried with those she sought to represent and encourage.

Instead, Evita took her place along side other members of the privileged with an address along a lane with rows and rows of other long dead patrons in their marble palaces. Walking down those lanes, peering at the names, the tombs, and the heavy marble walls, it wasn’t difficult to understand these dead had left a legacy for the living. It is one that most people in the world can understand. The elites, even those who pledge themselves to helping the poor and suffering, ultimately enter the afterlife in shrines erected for the few.

No one in the cemetery spoke of any irony in the incongruity of the slums and the marble mausoleums. Somewhere I am quite sure there is a marble tomb at La Recoleta Cemetery where the earthly remains of irony are housed. I didn’t find it. 4691 vaults is a lot to inspect on a cold, rainy Buenos Aries afternoon. Leaving the cemetery we came across a large, well-fed cat curled up into a ball under a tree in the shadow of a dead president. It was an ideal place to be a cat. After closing time when the tourists left and the rats came out of the shadows. The hunting must have been good. Like shooting fishing in a barrel. Rats stalking the dead, the cats stalking the rats, and not even a hint of irony in the ecology that has come to represent our time and place.

No one in the cemetery spoke of any irony in the incongruity of the slums and the marble mausoleums. Somewhere I am quite sure there is a marble tomb at La Recoleta Cemetery where the earthly remains of irony are housed. I didn’t find it. 4691 vaults is a lot to inspect on a cold, rainy Buenos Aries afternoon. Leaving the cemetery we came across a large, well-fed cat curled up into a ball under a tree in the shadow of a dead president. It was an ideal place to be a cat. After closing time when the tourists left and the rats came out of the shadows. The hunting must have been good. Like shooting fishing in a barrel. Rats stalking the dead, the cats stalking the rats, and not even a hint of irony in the ecology that has come to represent our time and place.

I am prepared for a Western post-irony future. After nearly twenty-five years living in Thailand, a culture rich in puns, riddles and word play but autistic when it comes to irony, I can give you a hint of what to expect next. Without knowing it, you begin to accept that incongruities aren’t really contradictions that need resolution. Reality is large enough and people are adult enough to not dwell upon such matters. Once you accept that premise not only is irony dead, it was stillborn.

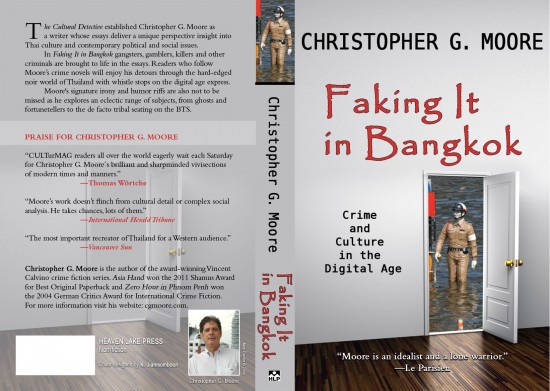

Christopher G. Moore

Dieser Text ist am 28. Juni auf unserer Partner-Seite erschienen.

The Wisdom of Beer

The Wisdom of Beer

Der Untreue-Index beim Unionsverlag. Bangkok Noir. The Cultural Detective. Kindle/Amazon. UK and Kindle/Amazon USA. His latest Vincent Calvino novel, 12th in the series, is titled 9 Gold Bullets and is available as an ebook on Kindle. Moores Podcast. Die Vincent Calvino-Romane. Der Autor beim Unionsverlag hier. Zu Christopher G. Moores Website und zu Tobias Gohlis’ Rezension des Untreue Index bei arte.tv.