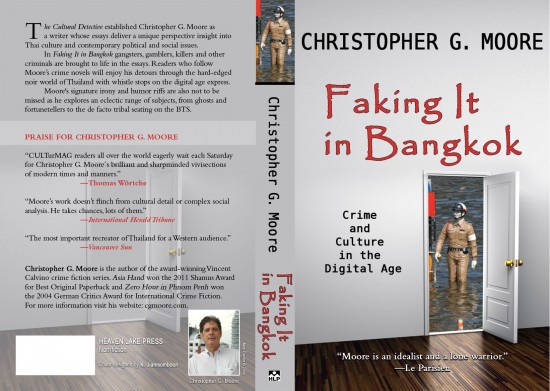

Christopher G. Moore diesmal über essentielle Dinge – über’s Schreiben, über Glück und Pech und Geld und kein Geld.

Rolling the Dice

Let’s say you’ve written a book. Or maybe you are thinking about writing a book. It might be a crime novel set in an exotic location. It might be a domestic comedy set in your hometown. But let’s not become sidetracked by worrying about location, theme, or characters. It’s more important to think about what it means to write a book. Or more precisely what it takes, or what you believe it takes to start that process.

Realize from the beginning that there is a degree of madness in the desire to write fiction. The isolation it requires from friends, colleagues, family, and neighbors is part of the madness, the estrangement from others. Writers build a wall between self and community in the act of writing, with the community on the other side of the wall. If that contradiction isn’t a sign of madness, then nothing qualifies.

Writing is a contradiction between thinking and doing, between individuality and society, and creating and consuming. We have these elements dissembled and broken in our lives as writers. Those whose glide path isn’t founded on words are both freer and more enslaved than others are. Freer hitched to the wagon of word building can be forced labor, another kind of prison. This is also the cause of the enslavement. Enslaved as they spent a lifetime using words to pick the locks on the prison but never managed to escape. A life of writing is filled with these no-way out contradictions.

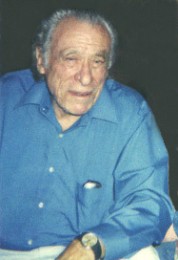

Charles Bukowski

I am writing these words because of two other writers seeking to find answers to these dilemmas faced by scribblers.

The first writer is Charles Bukowski and his poem “Rolling the Dice.” Have a listen to him read this poem. It is less than two minutes.

Just do it.

Bukowski says.

If you are going to try, don’t do it half-assed. You may suffer consequences: jail, derision, mockery and isolation.

It depends on how much you want to do. He says it is only the good fight there is.

If you want to write, then roll the dice. Do it. Do it now. You lose only by holding the dice you never throw.

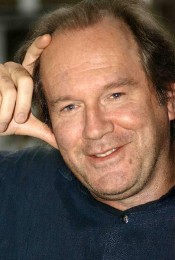

The second writer is William Boyd. He’s a well-known British novelist and his four part series Any Human Heart is worth watching. The main character is a writer named Logan Mountstuart. The background on the 2002 novel of the same title and the TV series is on Wikipedia.

William Boyd

In the TV series, Logan Mountstuart’s life as a writer starts at Oxford where he meets two other friends. One becomes successful novelist and the other friend becomes a highly noted art gallery owner in London and New York. Logan starts off with a bang in the literary world and then life intervenes, and he’s able to write another novel but never does. Instead he keeps a daily journal. The TV series explores the multi-selves of Mountstuart’s progression from a young child, to a young person, a middle aged one, and finally an old, frail man. Throughout this passage Mountstuart records the events of his life in a journal. The drama is drawn from those journals. What stays within his mind all through the years is the idea that what comes to a life is nothing more and nothing less than a matter of luck. What his father told him, good luck or bad luck. But it is luck.

While Bukowski whispers in our ear, ‘just do it’ as that is your only choice and what you wish to do is the only fight worth getting into the ring of life for. Boyd’s Logan Mountstuart wishes us to believe instead that whether you step into the ring or not, whatever happens, it is simply a matter of luck. Your wife that you love dearly is killed by a V-2 rocket walking down a London street with your daughter, you are arrested on a secret mission during WWII but the Swiss police stop you walking on a highway and throw you into prison, or you overlook the details of other’s motives, desires, illusions and that carelessness makes you unable to start a novel, or you choose the wrong woman as a lover or wife and again your novel writing venture stalls and crashes..

Logan Mountstuart spent a lifetime seemingly unable to do it.

Because he believed that it was all a matter of luck. In his world, you never had the chance to roll the dice. Others rolled it for you and however they rolled and stopped, that number became your destiny.

What a sad, dreary life of a life like a leaf blown in the wind.

Another reading is the end Moutstuarat’s life cycle was the time to allow the story to unfold from the journals. The grand irony was pointless as a way to create worlds when his world had been largely shaped by external events, circumstances and relationship. The luck component was the engine that did the shaping.

Logan Mountstuart who never got around to writing the bestselling novels like his Oxford friend ultimately is vindicated with the posthumous publication of his journals. In the closing minutes, we see the book cover of that book with Mountstuart’s handsome middle-aged face. Of course that made it fiction, too. As the point of the Journals was to chart a multi-character journey, and any snapshot of the author at one age was a greater distortion than found in fiction.

Moutstuart had luck. But he had to die before it came. What does success mean to a dead writer? Does it mean that he was ultimately lucky in the end even though he never lived to see it? When the dice were rolled, the winning number came not from his fiction but the artifacts of a life where the actions of others had determined his luck. Where was the line to be drawn between fiction and fact in Moutstuart’s life? I am not certain he ever knew. We certainly don’t.

As I said at the beginning, I’ve been thinking about Bukowski and Boyd, two authors with different visions of destiny, luck, hardship, consequences, and determination. Two approaches to what it means to be a writer.

Bukowski says, you roll the dice.

Boyd says, the dice are rolled for you.

And luck?

In Bukowski’s world there’s no such thing as luck. There’s only conviction, steadfastness and understanding that the isolation of climbing in the ring is the victory. That you have to struggle, fight back, make your luck each day. Or he might be saying, there is no luck. It’s all endurance and will and determination.

And in Logan Mounstuart’s world it’s all a matter of luck. This isn’t climbing in the ring. This is climbing on the stage to become a puppet that will be passed along from woman to woman, friend to friend, and a string of strangers. It doesn’t matter who they are really; as their only role is to pull the strings. How you move forward and backward in life is how lucky you when life assigns your quota of string pullers.

Writing a book is an act of endurance. Anyone who has done should be congratulated as it is often talked about but rarely done. If you’ve written a book to please the string pullers, then you rewarded like a puppet. Boyd has us believe the puppets die and disappear, vanish without a trace. But if your book questions the string pullers, condemns them, shows their duplicity, you can expect isolation. The reward is mockery, poverty, and loneliness. The truth never has come on the cheap. There are the costs to consider.

I am inclined toward the Bukowski school. Get in the ring. Throw a punch. Mix the metaphor, and roll the dice. Roll them before they roll you.

I am less inclined—though it may be my own delusion—to go along with Boyd’s Mountstuart. Because Logan Mountsuart’s life was nothing more than a series of random chance events and meetings—a man in the Spanish Civil War who left him a fortune in Miro paintings, his meetings with Hemingway in Paris, and Joyce and Ian Fleming, and his meeting and parting with a number of women over his life. These events and meetings became the frame around his own life. But what picture did Mountstuart finally leave inside that frame?

That’s the question. Did he leaves us only with the choreograph of a puppet show written daily and over a lifetime solely from the puppet’s point of view?

Is such a journal of luck the book we should all be writing? Is it the only legitimate book that can be written.

Again, I don’t know.

What I do believe is Bukowski’s three words should be pasted to your computer screen . . .

Just do it.

Christopher G. Moore

Dieser Text ist am 9. August auf unserer Partner-Seite erschienen.

The Wisdom of Beer

The Wisdom of Beer

Der Untreue-Index beim Unionsverlag. Bangkok Noir. The Cultural Detective. Kindle/Amazon. UK and Kindle/Amazon USA. His latest Vincent Calvino novel, 12th in the series, is titled 9 Gold Bullets and is available as an ebook on Kindle. Moores Podcast. Die Vincent Calvino-Romane. Der Autor beim Unionsverlag hier. Zu Christopher G. Moores Website und zu Tobias Gohlis’ Rezension des Untreue Index bei arte.