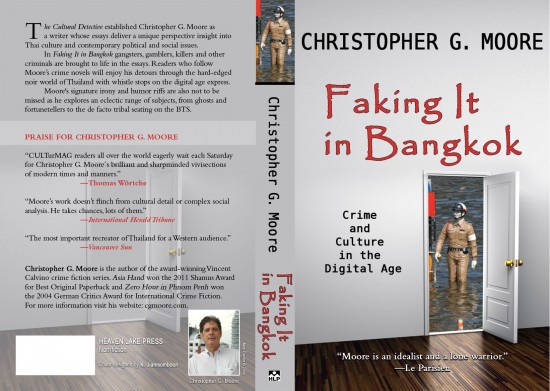

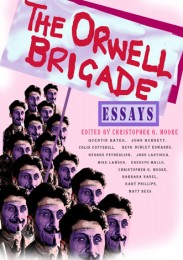

… Schriftsteller und Macht – ein prekäres Verhältnis. Auf jeden Fall sollen Schriftsteller dem „Staat“ misstrauen und ihm auf die Finger sehen. Christopher G. Moore und ein paar Gleichgesinnte, darunter Schwergewichte wie Gary Phillips, haben sich zur Orwell Brigade zusammengetan, um genau das zu tun: kritisch zu beobachten!

… Schriftsteller und Macht – ein prekäres Verhältnis. Auf jeden Fall sollen Schriftsteller dem „Staat“ misstrauen und ihm auf die Finger sehen. Christopher G. Moore und ein paar Gleichgesinnte, darunter Schwergewichte wie Gary Phillips, haben sich zur Orwell Brigade zusammengetan, um genau das zu tun: kritisch zu beobachten!

The State of Fear

The State of Fear

The first reaction to a threat or a possible threat is one of fear or anger. We are emotional by default and once our feeling and intuitions are engaged, our so-called rational mind’s duty is to justify the hot emotion that has us sweating and short of breath. When the State is the one creating fear, the emotions are heightened. Isn’t the State supposedly the one to protect us against those who would induce fear?

That is the story the State wishes us to believe. The dividing line between States isn’t so much democracy and autocratic but between those States which spin a story of protection against outside fear that most people believe is true. We are at heart, all of us, security seekers. That plays to the advantage of the State as the officials rely on the reality that there isn’t an alternative. A revolution merely changes those who operate the State and as history shows the new operators are no different than the ones they replaced—in many cases, they become addicted to terror to cow their rivals into submission.

Criminal laws regulate conduct and are the citizens’ first line of defense against the ‘wrongful’ or ‘bad’ conduct of others. In reality, many criminal laws authorize the State to protect itself against those who would challenge its authority. Broad and imprecise wording—like ‘national security’—allow those who enforce the laws broad powers and substantial penalties to charge, convict, and imprison a person whose activity is thought to be a threat to those in power. The threat of prosecution chills the exercise of free speech—stops political discussion. The State uses such power in the age of Internet access to censor what is sent and received by users.

The State is an intangible entity. We rail against an oppressive or abusive ‘State’. These emotional outbursts are like taking a swing at a cloud. You never quite connect your feelings with the object perceived to cause those feelings.

The State is an intangible entity. We rail against an oppressive or abusive ‘State’. These emotional outbursts are like taking a swing at a cloud. You never quite connect your feelings with the object perceived to cause those feelings.

The functionaries and officials who make up the State are many. They interact with each other. Some are more powerful than others, and there is an institutional bias or culture that prevails across those institutions as well as legacy traditions and customs within individual agencies. This makes assigning responsibility difficult. Who do you point the finger at when the State acts to criminalize political speech? Or criminalizes conduct that serves the interest of a small but powerful elite that benefit from a cone of secrecy and immunity from criticism?

In the new Orwellian world—everyone is guilty, and those charged are selected through the exercise of prosecutorial discretion to send a message to all the other potentially guilty citizens that they, too, are being watched and are vulnerable. And there is nothing they can do and no one to turn to.

Placed in the situation of being charged and the realization there was little chance of escape is thought to have led Aaron Swartz to commit suicide in New York. He was a 26-year-old computer genius, co-founder of Reddit, who’d been charged for ‘freeing’ academic data at M.I.T. Since his death there has been a firestorm of protest, questioning, criticism and hand-wringing.

The best piece written on why writers write is George Orwell’s essay On Writing 70 years ago.

The best piece written on why writers write is George Orwell’s essay On Writing 70 years ago.

Orwell said that the subject matter of a book is determined by the age in which the writer lives.

Context is what matters. Look around your space, inside the room where you are reading this essay, when you go out, look around the city. And think for a moment, it wasn’t always like this and won’t stay like this. But for the moment, the present, this is our context that determines how we think about books, each other, information, security, politicians, guns, drugs, pollution, women, police, and doctors and hospitals. We think of them in the now.

Commentary like this essay, films, books, comments others make online, are collections of our context where we find: social things, cultural things, psychological and political things. We try to make sense of all these signals, picking through the noise. It is hard work. The noise is always far greater than the signal. With the distractions and limited attention we can bring to anything directly in front of us should give us pause. It should give us a sense of humility. We are overwhelmed by the emotional words of others, the details pile up, the ambiguity increases. We hate doubt. We love certainty. One we avoid, the other we embrace.

Those employed by the State understand this bias. To avoid randomness and uncertainty gives the State actors an edge. Officials promise that they can and will remove the dread of doubt and once removed, we will feel safe and happy. The State understands that we are first and foremost emotional creatures. That insight is the source of their broad, vague powers and discretion.

We filter the justification, defenses, words of State officials as they weave a pattern that shows their actions are lawful, correct and in the interest of the State and its citizens. Orwell taught that writers had a duty to challenge these State manufactured patterns, deconstruct them, and offer original, alternative patterns. You can read volumes of Internet commentary taking this road about the official actions of the State in pursuing Aaron Swartz.

We filter the justification, defenses, words of State officials as they weave a pattern that shows their actions are lawful, correct and in the interest of the State and its citizens. Orwell taught that writers had a duty to challenge these State manufactured patterns, deconstruct them, and offer original, alternative patterns. You can read volumes of Internet commentary taking this road about the official actions of the State in pursuing Aaron Swartz.

The best writers communicate an essence of insight, meaning and purpose. They distinguish between intuition and rationale, objective evidence. To use Daniel Kahneman’s distinction, one is automatic, lazy thinking and the other is slow, deliberate thinking. They are connected. The lattice of biases that we all have ultimately shape and distort the way we think about reality.

The best books embody the way people think and feel. A good novel or short story hits an emotional chord in the reader that seems true.

The best books reflect emotional attitudes as people bumped up against the reality found inside the context where we live. The emotions we find floating above us include: Anger, hostility, envy, suspicion, jealousy, suspicion and deception.

Crime novels embrace these negative emotions and fine-tune them into stories where characters seek to escape their context, their destiny, or their moment in history. No matter how fast you write, the book is much slower than the click of a camera shutter, and even at that speed there is a transformation captured and the reality that follows that moment.

Orwell wrote that authors have four reasons or motives to write:

- Sheer egoism. The desire to appear clever, talked about, remembered after death. The great mass of people are far less selfish than writers. Serious authors are vain and self-centered.

- Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the patterns found in the exterior word and converted into prose. The firmness of good prose, the rhythm of a good story that carries you along.

- Historical impulse. To see things as they are outside of the filters, biases and prejudices that every context presents as barriers to truth.

- Political purpose. To use words to push the world in a certain direction—to shape or alter people’s idea of the kind of society we live in and whether that society is fundamentally just and fair.

Psychology has advanced a fifth reason Mindset Exploration to identify the connection between our emotional, impulsive, intuitive mind and our deliberate, rationale mind. To understand the interplay between the two aspects of our cognitive resources that create our system beliefs we defend and define the perimeters of our reality.

Aaron Schwartz

Our impulses war against one another and change over time, but our beliefs are difficult to shift even when the evidence is clear that what we believe is false or wrong. The Aaron Swartz suicide and background prosecution has ignited a debate about core beliefs about the role of prosecutorial discretion, freedom of speech, the nature of information, who owns it, has access to it, and can use and exploit it.

Context of Aaron Swartz’s death engages at the emotional level when the distrust of State actors and their bona fides are in doubt. His death is used to emotionally confirm our worst fears—the State is patrolling the products of our mind and our actions seeking to find violations of laws. And the question being asked is whose interests are being served in such prosecutions?

In The Orwell Brigade, a dozen authors, including Barbara Nadel, Quentin Bates, and Matt Rees who blog on this site, have joined John Burdett, Colin Cotterill, Ruth Dudley Edwards, Mike Lawson, Ernesto Mallo, and Gary Phillips to reclaim the role of telling truth to authority, to examine abuse of power, and to question the false histories and narratives officials use to justify their decisions and policies. The traditional media have retreated to the safety of entertainment and gossip to turn a profit. We have paid a high price for that retreat. One positive legacy of Aaron Swartz’s life is this questioning official exercise of power that once was done by journalists, essayists, and novelists has spawn a thousands, if not millions of voices. It is difficult even for the State to shut down, arrest, and lock up all of these people. I suspect they will lie low, wait for the faint breeze of time to blow away the anger. Once that happens the State, through its officials, will slowly creep back and remind us that without them we will live in a State of Fear.

In The Orwell Brigade, a dozen authors, including Barbara Nadel, Quentin Bates, and Matt Rees who blog on this site, have joined John Burdett, Colin Cotterill, Ruth Dudley Edwards, Mike Lawson, Ernesto Mallo, and Gary Phillips to reclaim the role of telling truth to authority, to examine abuse of power, and to question the false histories and narratives officials use to justify their decisions and policies. The traditional media have retreated to the safety of entertainment and gossip to turn a profit. We have paid a high price for that retreat. One positive legacy of Aaron Swartz’s life is this questioning official exercise of power that once was done by journalists, essayists, and novelists has spawn a thousands, if not millions of voices. It is difficult even for the State to shut down, arrest, and lock up all of these people. I suspect they will lie low, wait for the faint breeze of time to blow away the anger. Once that happens the State, through its officials, will slowly creep back and remind us that without them we will live in a State of Fear.

Christopher G. Moore

Dieser Text erschien am 17. Januar 2013 auf unserer Partnerseite.

His latest Vincent Calvino novel, 13th in the series, is titled Missing in Rangoon and is available as an ebook on Kindle.

Christopher C. Moore: The Wisdom of Beer.

Der Untreue-Index beim Unionsverlag. Bangkok Noir. The Cultural Detective. Kindle/Amazon. UK and Kindle/Amazon USA. Moores Podcast. Die Vincent Calvino-Romane. Der Autor beim Unionsverlag hier.

Zu Christopher G. Moores Website und zu Tobias Gohlis’ Rezension des Untreue Index bei arte.Foto Orwell: wikimedia commons, gemeinfrei; Foto Aaron Schwartz: wikimedia commons, Daniel J. Sieradski