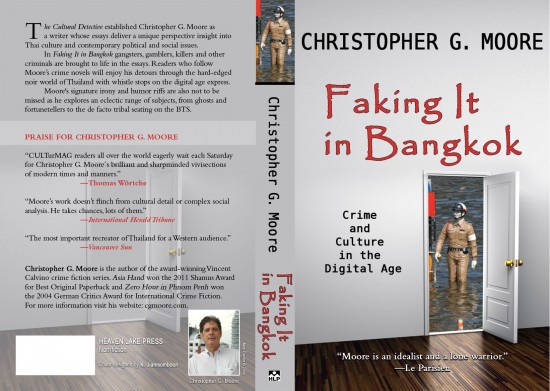

Manchmal ist es nützlich, einen lakonischen Reality-Check zu machen, um Literatur und Wirklichkeit sinnvoll sortieren zu können. Christopher G. Moore über einschlägige Fakten:

Manchmal ist es nützlich, einen lakonischen Reality-Check zu machen, um Literatur und Wirklichkeit sinnvoll sortieren zu können. Christopher G. Moore über einschlägige Fakten:

The Rate of Murder

You’ve decided to write that crime novel. The one book once released into the world will liberate you from the day job, put you on Charlie Rose, the NYT bestseller list, interviewed by the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times, and stacks of invitations to the best parties in New York, London and Paris. You’ve heard that international settings are in vogue for crime fiction. But you’re not quite certain, looking at the world map, which country might be the best place for your noir caper. Besides, you can write off the expense of research in finding out.

Let me give you some unsolicited advice, look for a place with danger—not too much, but enough to create tension and risk—political instability is good—again so long as there aren’t bombs going off in the streets, and an exotic culture with interesting taboos, customs, language, history, rituals and artifacts—though not so weird that they can’t be understood without long, drawn out descriptions.

A convention of the crime fiction genre begins with a murder. Central to the novel is a killing. When researching your crime novel, you might have a look at murder statistics. The homicide statistics indicate the prime crime fiction locations are the mini-states in the Caribbean or Central America. In these places there are lots and lots of murders as a percentage of 100,000 of population.

Homicide victims accumulate in these countries at an alarming rate. You can add Columbia and Venezuela to the high rate of homicide list, too. Frankly, you can write off Europe with the possible exception of Russia and Albania. The Europeans simply have stopped murdering each other at statistically significant rates. Germans seem to have stopped murdering each other in significant numbers a long time ago. Fantasy and romance novelists would do much better in Europe than crime fiction authors.

The ten countries with the highest murder are included in this chart:

Top Ten Countries with Highest Murder Rates

|

Country |

Murder Rates (Per 100,000) |

Year |

|

Honduras |

82.1 |

2010 |

|

El Salvador |

66.0 |

2010 |

|

Cote d’Ivoire |

56.9 |

2008 |

|

Jamaica |

52.1 |

2010 |

|

Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) |

49.0 |

2009 |

|

Belize |

41.7 |

2010 |

|

Guatemala |

41.4 |

2010 |

|

Saint Kitts and Nevis |

38.2 |

2010 |

|

Zambia |

38 |

2008 |

|

Uganda |

36.3 |

2008 |

If you want to write a noir crime fiction novel, then Honduras or El Salvador might be a place to go.

Places to avoid as a noir crime fiction writer are on this list:

|

Countries With Lowest Murder |

||

|

Country |

Region |

Murder Rate |

|

Monaco |

Europe |

0 |

|

Palau |

Oceania |

0 |

|

Hong Kong |

Asia |

0.2 |

|

Singapore |

Asia |

0.3 |

|

Iceland |

Europe |

0.3 |

|

Japan |

Asia |

0.4 |

|

French Polynesia |

Oceania |

0.4 |

|

Brunei |

Asia |

0.5 |

|

Bahrain |

Asia |

0.6 |

|

Norway |

Europe |

0.6 |

From these homicide rates, there isn’t enough raw material for a short crime story set in one of these countries. Though fellow blogger Quentin Bates who bases his crime fiction in Iceland, suggests that noir isn’t always reflected in the numbers.

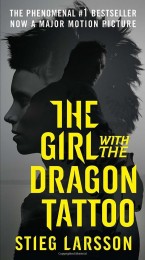

The numbers don’t tell you everything. Swedish crime fiction is a huge success internationally but the Swedish murder rate is among the lowest in the world. Yet we have a feeling reading Nordic crime fiction that murder is common in Sweden. That Sweden is a dangerous place. None of that is true. Sweden has a very low homicide rate. Those facts didn’t stop Stieg Larsson from hitting the jackpot (though he had died of a heart attack before the big money came in).

The definitive chart on the international murder is done on a country-by-country basis annually by the UNODC. Looking at the most recent figures from UNODC (2002 to 2011) on Thai murder rate has been in decline. If this trend continues, it seems that soon I may be out of the crime fiction business in Thailand.

The definitive chart on the international murder is done on a country-by-country basis annually by the UNODC. Looking at the most recent figures from UNODC (2002 to 2011) on Thai murder rate has been in decline. If this trend continues, it seems that soon I may be out of the crime fiction business in Thailand.

In 2003 the Thai murder rate was 9.8 per 100,000; and in 2011 it had dropped to 4.8 per 100,000. Do Thais feel 100% safer from being murder given this corresponding drop in actual homicides? I don’t have hard evidence to answer this question. There’s plenty of antidotal evidence to suggest no decline in the fear of being a murder victim. State authorities feed the fear and offer comfort as noted by Bangkok Pundit.

Why the disconnect between the declining murder rate and our sense of fear about murder? Our feelings are subjective, irrational, and difficult to predict or control. And fear of death and injury is one of the most compelling emotions, triggered not assuaged by a UNODC excel file that presents cold, hard numbers.

I take the position that Thais are no less concerned, fearful and watchful about murder in 2013 than they were in 2003. There is little political opportunity and advantage in reducing this unreasonable feeling of fear. In political life, money and fear correlate. More resources can be demanded by and allocated to the police and other state officials charged with protecting an overly fearful public. If our perception of the risk of murder is updated, then state officials stand to lose budgets, training, new employees, and better equipment. Actually, you can spend a lot of that money in ways that have little but public relations impact because the level of homicide is already happening. You can pocket some of that money and still be seen as doing a great job.

Bottom line—our emotional reaction to homicide hasn’t been updated with the latest statistics, which show a substantial lowering of the probability of murder. The state has no incentive to focus on the lower risk of homicide. The press will always have enough murders (even at statistically low rates people are still murdered just as people still win a lottery) to keep the flame high enough to keep fear at the boil.

When it comes to murder, we react out of fear and that closes the door to a more rational and deliberate assessment based on the actual risk as shown through the UNODC statistics on the rate of murder. Murders of foreigners make for dramatic news that reinforces the sense of fear. This happens in Thailand as in many other countries.

The media manufactures a false sense of risk with emotionally charged photographs, statements of witnesses, family and friends in mourning, angry letters to the authorities, and so on. If the murder victim is someone you love, care about or know, then UNODC statistics aren’t going to mean much to you. But if you are reading about people you don’t know, there remains a high possibility of identifying with them, and you will be fearful. Emotions distort your ability to assess the actual risk.

When it comes down to writing that crime novel, it may not matter whether you live in a country with a high or low murder rate. The rate of homicide appears to have little connection to the perception of risk as it is assessed through fear. As long as your novel creates a the personal setting between the killer and the victim, and does a credible job in following the police or private investigator through the evidence, your reader won’t likely write you an angry letter saying that statistically the murder you’ve written about is as rare as a rose in winter.

But as people love roses, if you can convince them to overlook the improbability of a rose growing in the wild in winter weather, they will follow you down the corpse laden garden trail and believe this exceptional act could happen in the world. Indeed it could happen to them. Yet you can be assured there will in the fullness of time an Amazon Reviewer, who will give you a one-star review that goes along the lines that everyone knows that only white roses grow in winter and this author had the color wrong. He said the roses were red. And that, my friends, is more likely than the wall cash your book will earn liberating you from your desk job.

Christopher G. Moore

Dieser Text ist am 21. März auf unserer Partner-Site erschienen.

Peter Münder über Moore im crimemag.

Christopher’s latest Vincent Calvino novel, 13th in the series, is titled Missing in Rangoon and is available as an ebook on Kindle.

Christopher C. Moore: The Wisdom of Beer.

Der Untreue-Index beim Unionsverlag. Bangkok Noir. The Cultural Detective. Kindle/Amazon. UK and Kindle/Amazon USA. Moores Podcast. Die Vincent Calvino-Romane. Der Autor beim Unionsverlag.

Zu Christopher G. Moores Website und zu Tobias Gohlis’ Rezension des Untreue Index bei arte.

Titelbild: Victor Bezrukov, wikimedia commons.