Die Rekonstruktion von Verbrechen kann für ihre Aufklärung wichtige Hinweise bringen, aber oft überwiegt das Spektakel und dann sind wir schon nahe an Shakespeare. Christopher G. Moore über eine bemerkenswerte Polizei-Praxis.

Re-enactement of Crimes – Reality checks

Theatre since the time of Greeks produced plays as a mirror to hold up to a society to see the reality of their existence. We are accustomed to the division of drama into the two different aspects of our lives—comedy and tragedy. We respond with laughter or tears as the emotional chords are played on our heartstrings with the virtuosity of the great dramatist. Not all cultures draw their dramatic heritage from the Greeks or Romans, nor are all dramas the product of professional stage producers, scriptwriters and directors.

In Thailand the police have an exclusive on the right to stage the drama of a criminal reenactment. A number of times a year it is show time in the Land of Smiles.

The police re-enactment of crimes has been refined over many years in Thailand until it has reached the level of an anticipated theatrical event. The reconstructions of actual crimes might be thought to be closer to carnival or street theatre than Shakespearian tightly scripted plays. The police having caught the criminal arrange for him or her (most of the time it’s him) to appear in front of the media and show how the suspect committed the crime. The police are casted in the role of heroes, the villain (sometimes there are more than one) is the real-life suspect and everyone plays their role before news reporters and TV cameras.

This is a different concept than the TV show like Crime Stopper, where to catch a criminal, the police reenact the crime in order to engage the public with a request for information to assist in identifying and arresting the suspect.

In Thailand, the police arrest the suspected criminal who has “confessed” to the crime. What follows the confession is a media presentation where the suspect, actors, and the police stage a reconstruction of the crime.

Reenactments can carry a light note, a hint of comedy with a suspect who has the media spotlight. That certainly proved to be the case with Carlo Konstantin Kohl who escaped from the airport by a German national where he’d been held in the transit lounge on his journey from Australia to Germany.

Sometimes the ‘theatre’ moves from the realm of controlled drama produced and directed by the police, to ‘live’ drama, which shows just how badly things can go wrong with a staged re-enactment of a crime.

In a recent criminal case, a Vietnamese national, a suspect in an abduction case was on his way to a crime scene reenactment, escaped out of the back of a police van.

When a 17-year drug addict reenacted the vicious stabbing of a maid in Phuket—she was stabbed 80 times and her throat slit—relatives and neighbors tried to beat up the suspect and the police had to intervene to protect him. As he was a minor his face was covered by a balaclava.

In the case of a sexual assault and robbery of two Russian women, the police had Thai actresses play the role of the Russians in the reconstruction of the crime. Obviously a ‘reconstructed’ crime doesn’t actually reproduce all the elements of the crime. It is more like a power point presentation of how to fly an airplane than actually getting in the cockpit and taking off.

The Nation reported the police rationale for reenactments of crime:

“A Metropolitan Police specialist said a re-enactment is important for an investigation because each criminal or each gang behaves differently in committing a crime. Details on how criminals commit each crime help the police understand the pattern of a crime. This can help them track down other criminals showing the same behaviour pattern and help reduce the loss of life and property.”

Reenactments as a police school teaching tool for crime investigators strikes me as an interesting, though implausible, heuristic tool. I think the jury is out exactly how such reenactments expand the range of knowledge about criminal behavior. Watching Superman in Man of Steel might impart some knowledge about criminal conduct as well. Crime re-enactments, in my view, touch on a much older idea about communities gathering to witness a wrongdoer repent, confess his crime, show his contrition by assisting the authorities in demonstrating what he did. Reenactments are a ritual, like rituals surrounding birth, marriage and death. Rituals of cleansing the wrongdoer—with the police as high-priests—are on hand as representatives of the gods who punish those who do wrong, so that victim’s family, friends and neighbors can watch the suspect admit his sin.

If the police explanation is correct, the re-enactments ought to take place in an actual theatre or classroom. From the photos below, you can see the Thai police staged a re-enactment of the murder of a well-known and controversial businessman is being witnessed by only two officers (with one having his interest engaged elsewhere).

Another point, which also isn’t explained, is why the press is invited to record this piece of theatre, the large number of police officers who attend such reenactments, or onlookers who are allowed to watch the whole proceeding up close. Are they training sessions or workshops? Or is this staged reconstruction more like theatre? May be it is a ritualized repentance and request for forgiveness as I discussed earlier. Or could it be an effective way of communicating with the public that the police not only have solved the crime, protected them, and by locking this man up they are keeping them safe? As we’ve learnt with recent events in the intelligence community in America, the desire to feel safe is a license to do whatever is necessary to accomplish that goal. Reenactments are hatched from a primordial fear of danger from other people.

A member of the National Human Rights Commission, Paiboon Warahapaitoon, requested that the police take into account the human rights implications arising from staging a reenactment of a crime. Even under Thai law, the accused can’t be convicted solely based on a confession. A reenactment is no more than a dramatization of a confession that cannot be used to convict, unless it is supported by independent evidence of guilt.

Western lawyers have come out to argue that the Thai police reenactments would be illegal in most countries.

Most of the Thai reenactments are young Thais with little education and from poor families. These are the faces one sees among the suspects reenacting crimes. The rich and well-off are not actors in these dramas. They have their lawyers, day in court, and are usually out on bail, denying the charges against them.

Last week a Thai diplomat stationed in Cario was involved in an altercation in a luxury hotel. The facts are yet to be finally established, but the preliminary reports having the young Thai woman diplomat kicking, scratching and biting an Egyptian lawyer in front of her husband and other witnesses after a round of insults at Egypt and Egyptian people . The diplomat has claimed self-defence, but offered no details as to what caused her to be threatened. The Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs has recalled her to Bangkok and said it will investigate the matter. Whatever is found, one thing you can be assured won’t happen is a reenactment of the incident.

If you want to see how the rich carry on, watch primetime Thai TV lakorn (soap operas) on free TV channels. They are the next best thing to crime reenactments of assaults and other crimes the privileged commit. Lakorn is wildly popular amongst a large segment of the population. This shows there is a popular appetite for reenactments of crimes, nasty and anti-social behavior which don’t quite rise to crimes but nonetheless inflict a fair measure of emotional damage to the victims.

For this reason I think it is unlikely that the popularity of the Thai lakorn will wane any time soon. And the same can be predicted for criminal reenactments starring members of the underclasses. All societies need a way of staging drama. Each culture evolves a set of expectations, roles, producers, directors and media stars. The Thais give the starring roles to the poor in reality news entertainment in crime re-enactments, and the rich get theirs in soapy primetime TV dramas. Thai audiences are as entertained as any member of the old Globe Theatre in London. The show must go on. And when the price of admission is free, and the villain at center stage performs his role, for that moment, he achieves a moment of fame. And the police reinforce their image as heroes, defenders, protectors against the ‘other’ who are out ‘there’ waiting to kill, maim, rob, rape or assault.

Shakespeare in Richard II wrote: “As in a theatre, the eyes of men, after a well-graced actor leaves the stage, are idly bent on him that

enters next.” And who enters next may well be someone caught on a video camera. Digital video recorders in cell phones have the

potential, over time, to replace the police reenactment. The purpose of the reenactment is for the suspect to show how he committed the

crime. In this YouTube clip a Thai man confronts Russian man with a handgun in Phuket. It is over a woman.

Videos like this eliminate the need for a reenactment.

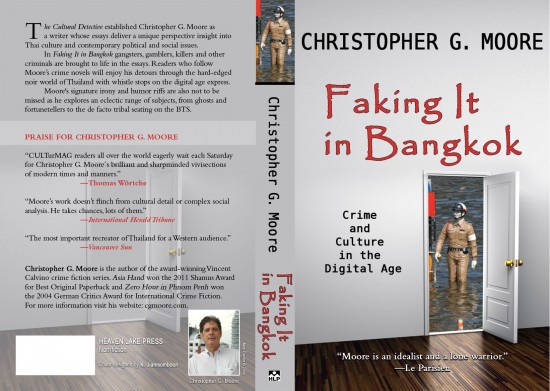

Christopher G. Moore

Diese Kolumne erschien am 20 Juni auf unserer Partnerseite.

Christopher’s latest Vincent Calvino novel, 13th in the series, is titled Missing in Rangoon and is available as an ebook on Kindle.

Christopher C. Moore: The Wisdom of Beer.

Der Untreue-Index beim Unionsverlag. Bangkok Noir. The Cultural Detective. Kindle/Amazon. UK and Kindle/Amazon USA. Moores Podcast. Die Vincent Calvino-Romane. Der Autor beim Unionsverlag.

Zu Christopher G. Moores Website und zu Tobias Gohlis’ Rezension des Untreue Index bei arte.

Titelbild: Victor Bezrukov, wikimedia commons.