Die Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika sind eine gespaltene Gesellschaft mit unterschiedlichsten Konfliktlinien und einem scharfen Arm/Reich-Antagonismus sowie einem trotzigen „dennoch“-Optimismus. Thomas Adcock beleuchtet ein paar Hintergründe, die helfen, den aktuellen Wahlkampf (den Adcock ab dem nächsten Montag wöchentlich aktuell und exklusiv für CULTurMAG kommentieren wird) zu verstehen.

Rx heißt übrigens in diesem Zusammenhang prescription, also Arznei-Rezept …

The American Spirit of Optimism:

Rx for Lousy Times

by Thomas Adcock

American plutocrats have a natural alliance with corporations, bankers, and true believers in laissez-faire capitalism. To keep the riff-raff from rising up in anger, the plutocracy relies on a proven strategy: encourage the middle and working classes to squabble endlessly amongst themselves over matters of race, religion, wages, sex, and bourgeois politics.

This is the standard ruling class blueprint for a social order in which they occupy the mountaintop. It has ever been so, and is hardly exclusive to the United States.

From time to time, American plutocrats grow dissatisfied with the power and privilege they hold, no matter how great the amount, and commence grubbing for more—and more, and more. Occasionally, the rude hordes resist on mute impulse. When this happens, a marriage of conflicting castes is consummated: great wealth takes a naïve bride in the great resentment of those on the margins of propertied society.

Such is happening in the United States in this presidential election season. Woe unto the rest of the world if the better angels of America fail to win the battle. Happily, and despite all that is wrong with my country, there is a national spirit of optimism and altruism that dates back our very beginning.

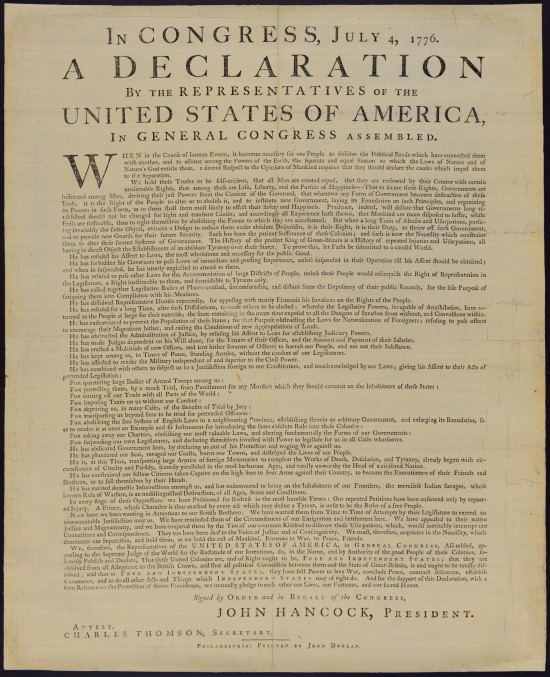

This spirit, defined by the American Declaration of Independence, may assure the world that not all of us have lost our minds. I shall explain.

•

In 2010, members of America’s socio-economic elite leveraged traditional power to historically worrisome heights by tucking in with strange new political bedfellows: bigots, know-nothings, gun fanatics, proto-fascists, religious zealots, the obtuse and the fetus-obsessed who call themselves “patriots” of the “Tea Party.” The title they chose alludes to a gang of colonial era vandals who, in 1773, forcibly boarded British ships in the Boston harbor and dumped their cargo into brackish water as a protest against usurious import taxes on English tea.

Tea partiers now firmly control the once respectable Republican Party, founded by President Abraham Lincoln in the mid-19th Century as an anti-slavery movement and carried forward as a progressive force through much of the 20th Century by successor Republican Presidents Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt and Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower, among others. Besides patriotic, tea partiers consider themselves conservative in political temperament, despite scant evidence of their conserving much of anything championed by Abe, Teddy or Ike; in fact, they have vandalized what remains of the Republican ship they boarded, like pirates.

Tea partiers believe that American liberals, the progressives of yore, are evil—as evil as European socialists! They conflate liberalism and socialism, holding these philosophies as antithetical to what they term “original intent” behind the words of America’s founding fathers. While they regard the U.S. Constitution and Federalist Papers as holy writ—like the Holy Bible, however, these documents are largely unread—self-styled “conservatives” seem uninterested in, or perhaps ignorant of, the spirit of collective optimism articulated by the final and inherently liberal sentence of the Declaration of Independence:

John Hancock

On July 4, 1776, quill pens in hand, John Hancock and fifty-five comrades proclaimed the core intent of the United States in putting their names to an elegant document ending with a defiant notion of communal society, an idea that shook and continues to shake the world:

And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Back then, such daring social compact existed nowhere else but in thirteen rustic colonies willing to take up arms against the oppression of King George III. Even today, the spirit of John Hancock and his gang of aristocrats—whose cohorts included Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John and Samuel Adams: optimists all who risked their lives and property as signatories to revolution—is rare.

But that optimistic spirit—a spirit that drives all American progress—has been at historic odds with a negative impulse among the American people: a selfishness that paradoxically afflicts both the afflicters and the afflicted, as we see in the current political season.

Joseph Stiglitz

A second Gilded Age

Outlandish wealth and tax policy are much at issue this American presidential campaign year—in particular, tax rates assessed against the wealthy: Mitt Romney’s 13.9 percent bite in 2010 for instance, versus more than double that which Uncle Sam removes from the average Joe’s pocket. Some would say that such a schism was not the original intent of John Hancock, et al. And yet, the divide is co-championed by the usual suspects in cahoots with a low-information proletariat, as revealed by Thomas Frank’s 2004 book, “What’s the Matter with Kansas? How ‘Conservatives’ Won the Heart of America.”

For many, it is difficult to maintain a positive view with respect to America’s future, for the country seems mired in yet another dreadful Gilded Age. (Take note of the peculiarly optimistic ring we Americans apply to injurious epochs.)

In his syndicated newspaper column of June 10, 2012, Columbia University’s Joseph E. Stiglitz wrote of alarming dystopia, “America has the highest level of inequality of any of the advanced countries, and its gap with the rest has been widening.”

Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate in economics, continued, “In the ‘recovery’ of 2009-10, the top one percent of U.S. income earners captured 93 percent of the income growth. Other inequality indicators—like wealth, health, and life expectancy—are as bad or worse. The clear trend is one of concentration of income and wealth at the top, the hollowing out of the middle, and increasing poverty at the bottom.”

Matt Taibbi

Matt Taibbi, the profane chronicler of Wall Street oligarchs for Rolling Stone magazine is unlikely to be recognized for politesse by the Nobel Committee. He speaks of misdirected anger and jealousy on the part of American proles. Establishment Democrats who speak for those of lesser wealth are accused by the Republican Tea Party axis of fomenting “class warfare,” a disingenuous locution that has not so much divided the rich from the poor and struggling as it has sewn dissension in the lower ranks.

“We have met the enemy,” observed the cartoon character Pogo in 1971, “and he is us.” Or as Taibbi put it in February of this year, “It’s not envy of the rich. That’s not what good peasants do. It’s envy of the poor slob next to you, the one you closely resemble; who has the extra nickel you don’t.”

Stiglitz and Taibbi, and perhaps Pogo, reflect the reasoning of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis (1856-1941), who came of age during a previously gluttonous period of corporate greed, commencing with northern victory in the American Civil War and ending with the collapse of Wall Street during the “panic” of the 1890s. From this, Brandeis drew a lesson in need of remedial study and review: “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

In the wake of the Gilded Age of the 19th Century came the Progressive Era of the early 20th, personified by Teddy Roosevelt (1858-1919), a Republican who famously destroyed corporate monopolies, reformed banking laws, and promulgated the “Square Deal” to increase equitable standing on the union side of labor relations. Following yet another in the long line of Wall Street crimes and greedy shenanigans, Teddy’s cousin, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945), a Democrat who carried progressivism forward by way of “New Deal” creations such as Social Security, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Fair Labor Standards Act, and the Glass-Steagall bank reform act.

The Roosevelts’ bipartisan accomplishments were attacked from the start, and have been attacked ever since, by the participants of organized selfishness, headquartered in—where else?—Wall Street. Consequently, and over time, banking and labor laws were greatly eroded. Case in point: at the behest of President Bill Clinton and fellow Democrats under corporate subsidy, Glass-Steagall was repealed in 1999—thus removing strictures against the very kind of Wall Street speculation that caused the stock market crash of 1929, and in 2007 ushered in the Great Recession from which many will not recover.

Howard Zinn, 2009

But wait, there’s more!

Nonetheless, there are corporation-free voices of uplift in the land that hark back to the Declaration of Independence, and its spirit of defiance; voices that speak truth to arrogance and corrupted power. These are the voices to revive our sometimes flagging American spirit, a spirit birthed in audacious rebellion against the mightiest political, economic, and military empire extant in July of 1776.

Two centuries and three decades later, in 2006, the historian and activist Howard Zinn wrote, in the righteous fashion of our founding fathers, “The struggle for justice should never be abandoned because of the overwhelming power of those who have the guns and money, and who seem invincible in their determination to hold on to it. That apparent power has, again and again, proved vulnerable to human qualities less measurable than bombs and dollars: moral fervor, determination, unity, organization, sacrifice, wit, ingenuity, patience.”

To which the British comedian Ricky Gervais would add: the jaunty spirit of his American cousins. In a clever video for the website “Open Culture,” Gervais compared us to his English countrymen: “Americans are slightly smarter, they’ve got better teeth, they have more ambition, they’re slightly broader, and they’re more optimistic. Americans are told they can become the next president of the United States, and they can.”

Besides good teeth and optimism, we may rely on other markers along a path of departure from national malaise: love—and love’s next of kin, hope. And, conversely, the hypocrisy of those who militate against all things progressive and Rooseveltian, Franklin or Teddy.

Sooner or later, the stink of hypocrisy ripens; everyone’s nose wrinkles in disgust, and a hypocrite’s putrid lies are put to death, or laughed off the stage. (Fair warning, tea partiers!)

Ayn Rand, 1957

Rank hypocrisy is the realm of Ayn Rand (1905-1982), progenitor of a “moral philosophy” that celebrates unbridled self-enrichment while excoriating poor and middle-class “parasites,” “looters” and “moochers” who collect any manner of public welfare benefits—or even tax-based government entitlements. Her “objectivist” essays and schlock novels—“The Fountainhead,” “Atlas Shrugged” and the ilk—are required reading for staffers employed by the current Republican Tea Party candidate for vice president, Congressman Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, author of a federal budget bill that would abolish Social Security and Medicare as we have known these programs.

But wait, there’s more!

It happens that Ayn Rand collected both Social Security and Medicare—slyly, by way of her marriage license, as Mrs. Frank O’Connor. Mr. O’Connor’s beloved was outed in January 2011 by Michael Ford, director of the Center for the Study of the American Dream at Xavier University in Cincinnati.

“In the end, Miss Rand was a hypocrite,” Ford wrote, “but she could never be faulted for failing to act in her own self-interest.”

Studs Terkel, 2007

Hope & Love

As for hope, it may best be illustrated in the life and work of Studs Terkel (1912-2008), the ebullient author and radio broadcaster. “It’s realistic to have hope,” Terkel said, many times in many episodes of his long-running interview show for Chicago’s WFMT. “It’s practical to hope because the hope is for us to survive as a human species. That’s very realistic.”

One radio day, Terkel said, “I have hope because what’s the alternative? Despair? If you have despair, you might as well put your head in the oven.”

Some would count the contemporary journalist Chris Hedges as among the despairing sort, what with his unsmiling demeanor and customarily downbeat, distressingly pious discourses on the current condition of America—crippled once more by the unindicted criminals of Wall Street. The trouble this time sorely tests our spirit, as Hedges chronicles in his sourest book— “Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle,” an examination of our terrifying national decline.

Even so, Hedges winds up helpless against the inescapable mark of his American roots. For he ends “Empire of Illusion” with the grace of a native optimism in which we all must share and trust, most assuredly now:

The power of love is greater than the power of death. It cannot be controlled. It is about sacrifice for the other—something nearly every parent understands—rather than exploitation. It is about honoring the sacred. [P]ower elites for millennia have tried but failed to crush the force of love. Blind and dumb, indifferent to the siren calls of celebrity, unable to bow before illusions, defying the lust for power, love constantly rises up to remind a wayward society of what is real and what is illusion. Love will endure, even when it appears darkness has swallowed us all, to triumph over the wreckage that remains.

Since early this spring, I have predicted a resounding victory this November for Barack Obama. Few took me seriously then. Many now do.

For me and for others, the promise that we shall heed the voices of our better angels was made by President Obama, as he echoed the centuries-old spirit of American optimism during his party’s nominating convention in the second week of September:

For me and for others, the promise that we shall heed the voices of our better angels was made by President Obama, as he echoed the centuries-old spirit of American optimism during his party’s nominating convention in the second week of September:

We, the people, recognize that we have responsibilities as well as rights; that our destinies are bound together; that a freedom which only asks what’s in it for me, a freedom without commitment to others, a freedom without love or charity or duty or patriotism, is unworthy of our founding ideals, and those who died in their defense.

Copyright © 2012 by Thomas Adcock

THOMAS ADCOCK is a novelist and journalist based in New York City. Winner of the prestigious Edgar Allan Poe Award, given by Mystery Writers of America, his books and articles have been published worldwide. Writing as Tom Dey, he is currently completing a new novel titled “Lovers & Corpses.” Mehr zu Thomas Adcock hier und hier.