Christina Mohr –

Christopher G. Moore (e) –

Peter Münder –

Marcus Müntefering –

Andrew Nette (e) –

Jim Nisbet (e) –

Christina Mohr

Meine Top 10 Alben

Roisin Murphy: Roisin Machine

Something More:

Stella Sommer: Northern Dancer

Seth Bogart: Men on the Verge of Nothing

Sneaks: Happy Birthday

U.S. Girls: Heavy Light

Rufus Wainwright: Unfollow the Rules

Sault: Untitled (Black Is)

Public Practice: Gentle Grip

Sparks: A Steady Drip, Drip, Drip

Jessy Lanza: All the Time

Meine Top 10 Songs

The Weeknd: Blinding Lights

Chris Imler: Country Club

Arlo Parks: Hurt

Benee: Supalonely

Jessy Lanza: Face

Salomea: In This Together

Shirley Holmes: Wieder sehen

Becca Mancari: First Time

Perfume Genius: On the Floor

Dream Nails: Vagina Police

Meine Top 10 Bücher

Kathy Valentine: All I Ever Wanted

Chris Frantz: Remain In Love

Deniz Ohde: Streulicht

Sebastian Janata: Die Ambassadorin

JJ Bola: Sei kein Mann

Rebecca Solnit: Unziemliches Verhalten

Lydia Davis: Es ist, wie’s ist

Mary MacLane: Ich erwarte die Ankunft des Teufels

Jens Rachut: Der mit der Luft schimpft

Andrea Petkovich: Zwischen Ruhm und Ehre liegt die Nacht

Christopher G. Moore: 2020 Roundup

I’m pretty sure after receiving this long tome both Alf and Thomas will banish me from further roundups. It’s been a crazy year. It has also been an extremely productive year.

The Book: To wrap up for 2020 I will start with Dance Me to the End of Time, the 17th and final novel in the long-running Vincent Calvino crime novel series which was published on 27th January 2020. I think of 2019 as the end of an era. A new one started in 2020. Where it is going and how our lives will be subject to accelerated forces of transformation.

The search is on for new ways to express in words and images the new world we are entering. Dance me to the End of Time is a literary leap into the future with a private eye who had earned his stripes in the old era.

After 30 years in the trenches, Calvino has retired to live in a future Bangkok at the start of a pandemic (the book was written in 2019 before Covid-19). We find Calvino using his survivable and detection skills in a climate changed, desolate Bangkok; one pocked with sinkholes with an AI overlord whose job includes separating warring clans who clash as their online avatars and later in the physical, darker, more dangerous analogue world.

The CCCL Film Festival: Climate change projects have dominated 2020 and I believe will continue to do so as the impacts of climate become more widespread, damaging, and irreversible.

In 2019 I founded Changing Climate, Changing Lives Film Festival (CCCL Film Festival) It has since grown into an organization involving many NGOs, embassies, UNDP, and corporate sponsors and partners. The first festival was held at ThaiPBS in Bangkok on 21st and 22nd November. Our partners this year included The Goethe Institute and the Henrich Boll Foundation.

This is the group photo taken the night of the award ceremony. ThaiPBS program called 2degrees produced an episode featuring the CCCL Film festival 2020. We will be taking the show reel of the winning films into schools and universities, holding workshops and touring neighboring countries in Southeast Asia to inspire the youths to take up a camera and tell the story of mitigation and adaptation to climate change.

The Art Exhibition. Early in December 2020, I opened an art exhibition at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Thailand titled The Great Upheaval: Mapping of Calvino’s World is the result of Edward’s deep dive into a series of striking images of the terrain of this unknown place.

Seventeen prints—Edward defines them as Stations—document his struggle to visualize what lies ahead. The art takes you down the rabbit hole and through the tunnels explored in Dance Me to the End of Time.

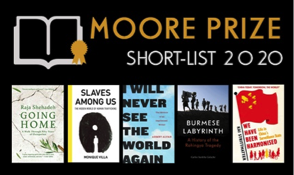

Moore Prize 2020: The judges for the Moore Prize 2020 has announced its short list. The winning title will be announced in London on 11th January 2021. The prize honors the best book deemed to advance our understanding of human rights.

The 2020 jury was comprised of Jonathan Head, Catherine Morris and Djamila Ribeiro.

The 2017 Moore Prize was awarded to Anjan Sundarm for Bad News and the 2018 Moore Prize was awarded to Deepak Unnikriskan for Temporary People. The 2019 Prize was awarded to The Sun Does Shine by Anthony Ray Hinton

Big Impact Books Webcast. In December 2020, I will launch a webcast show: Big Impact Books, a twice-monthly webcast featuring one-on-one interviews with the world’s leading scientists, thinkers, pundits, intellectuals in a discussion about the books that have shaped their worldview. Our guests will have distinguished themselves in their field as original thinkers. In the program my mission is to decode the reading that helped make that originality and creativity possible. Here’s a look at our first show. You can check out Big Impact Books on YouTube. If there is someone one you would like to appear on the show, let me know.

Christopher G. Moore who lives in Thailand, is our Asia correspondent. His essays on CrimeMag. His website. Answering Bloody Questions from Marcus Müntefering.

Marcus Müntefering: Worst of 2020

Und dann stirbt auch noch John le Carré, dieser feine Mensch und große Autor – wer soll denn überhaupt noch Lust haben, sich über dieses absolut beschissene Jahr Gedanken zu machen, an was bloß sollten wir uns erinnern wollen? An Absagen, Ausfälle, Pleiten, Kranke, Tote? An die Musiker, die Schriftsteller, die Filmleute, die freien Journalisten und all die anderen, die nicht wissen, wie es weitergehen soll? An die Bars und Clubs, die vielleicht nie mehr aufmachen? An die Covidioten, die ihre Dummheit wieder und wieder unter Beweis stellten? An den orangenen Wichser in Washington und seine Machenschaften auch nach der verlorenen Wahl? An seinen dummdreisten Zwilling in Downing Street 10? An all die anderen Despoten und gernegroßen Vollidioten, die die Welt weiter ins Elend stürzen?

Verdammte Hecke, zu diesem Jahr fällt mir nichts ein. Hauptsache, es wird Fußball gespielt und die Lufthansa fällt nicht vom Himmel, nicht wahr? Alles andere ist doch wirklich nicht systemrelevant.

Also, vergessen wir das Jahr 2020, gedenken wir vielmehr der Menschen, die uns im nächsten, bestimmt nicht viel besseren 2021 nicht mehr begleiten werden, aber deren Kunst für immer bei uns ist.

Macht’s gut und trinkt einen auf uns hier unten, Boys and Girls (and whatever or whoever you want to be). Von mir also nur wenige Worte, dafür ein bisschen Musik von ganz besonderen Menschen, die 2020 nicht überlebt haben. Mr John Prine, Mr Justin Townes Earle, thank you for the Music!

Und vor allem: Genesis Breyer P. Orridge, thank you for everything! Du hast allen, die hören und sehen wollten, gezeigt, welche Pfade ein Mensch gehen kann, auch wenn er sie erst schaffen muss.

Trans-Gression, Baby!

Marcus Müntefering bei CrimeMag hier.

Peter Münder: Spannender Lockdown mit Trilogie-Lektüre

Wann, wenn nicht jetzt, haben wir die ideale Schmökerphase? Die Zeit für intensiveres Hineinkriechen in Bücher, die ungefähr das „Krieg und Frieden“-Volumen haben und uns auch nach mehrtägiger Lektüre noch stark beschäftigen? Kurz vor Corona konnte ich noch eine Auszeit auf den Kanaren mit Sonne, Schwimmen, Radfahren, Wandern und Lesen am Pool genießen und dann ging es auch schon ab in die Corona-Klausur – was aber angesichts der aufregenden Stieg Larsson-Trilogie mit rund 2000 Seiten und der Dos Passos-USA-Trilogie mit 1100 Seiten (Penguin-TB englisch) und 1600 Seiten (Rowohlt, dt. Neu-Übersetzung) zum Hochgenuss wurde.

Die schwedischen Ermittlungen zum Palme-Mord schienen nach 34jährigen Ermittlungen jetzt im Sommer kurz vor der Aufklärung zu stehen und da fiel mir ein, dass ich von den drei Millenium-Bänden (im Schuber, für zwanzig Pfund im Bookshop des Gatwick-Airport gekauft) um die Meister-Hackerin Lisbeth Salander bisher nur einen – nämlich The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet´s Nest – gelesen hatte. So tauchte ich also ein in die schwedische Unterwelt, in der sich rechtsradikale Geheimdienstler innerhalb der SAPÖ-Polizei eine eigene Truppe mit schlagkräftigen Aktivisten („Informationsbyran“/IB) zugelegt hatten und ihre Mitglieder trotz übelster illegaler Aktionen nie auf dem offiziellen Bürokraten-Radar auftauchten.

Stieg Larssons Recherche-Unterlagen zum Palme-Mord (vier Kartons) wurden ja erst nach seinem Tod gefunden. Aber in seiner Trilogie beschreibt er das von Kriminellen unterwanderte schwedische Establishment eigentlich als mafiöse Bande, die mit ihren Beziehungen zu Medien die Öffentlichkeit so komplett irreführen, manipulieren und aufhetzen kann, dass die konstruierten Feindbilder sich kaum vom Irrsinn und dem Verfolgungswahn des hysterischen Egomanen im White House und seinen Stiefelleckern unterscheiden. Daher hätte ich mich auch nicht gewundert, wenn Larsson Slogans wie „Make Sweden Great Again“ in seine Trilogie eingestreut hätte – die Auswüchse von Rassismus, rechtsradikaler Gewalt und Frauenfeindlichkeit hat er jedenfalls in drastischen Szenen festgehalten und das Totalversagen des Justizapparats beleuchtet. Als im Sommer 2020 dann in Stockholm Stig Engström als Palme-Mörder vorgeführt wurde, war die Posse bis zum aberwitzigen Höhepunkt getrieben worden: Der alkoholkranke Grafiker Engström hatte sich vor 20 Jahren das Leben genommen, war aber damals nach dem Attentat auf Palme einer der ersten gewesen, der sich bei der Polizei als Täter ausgab – doch der Apparat ermittelte in andere Richtungen, weil ein Ober-Bürokrat sich auf die kurdische PKK fokussiert hatte und unbedingt irgendwelche suspekten Kurden in den Knast bringen wollte. Nach der Urteilaverkündung wurde übrigens auch das Totalversagen der Justiz offenbart: Kritische Beobachter der Palme-Ermittlungen kommentierten diese über 34 Jahre andauernden Aktivitäten von Polizei und Justiz als „Versuche, nichts auszulassen, was dumm und falsch war“. Der Reporter, Grafiker und Autor Stieg Larsson hatte übrigens als Illustrator der Agentur TT nach dem Palme-Mord den Auftrag bekommen, eine Skizze vom Tatort anzufertigen. Diese und andere Details zu Larssons Interesse am Fall Olof Palme hatte Jan Stocklassa 2018 dazu inspiriert, sein Buch Stieg Larssons Erbe zu schreiben. Nach 34-jährigen völlig unergiebigen Ermittlungen, meint Stocklassa, müsste man wohl weitere 34 Jahre auf ein zufriedenstellendes Ermittlungsergebnis warten.

Wie auch immer: Die Lektüre der Larsson-Trilogie war auch deswegen besonders faszinierend, weil der Roman fast wie ein Kommentar zu laufenden Ereignissen wirkte – inklusive einer medial angeheizten Hysterie angesichts tückischer Feindbilder und dem fast überall präsenten Verfolgungswahn. Fakt und Fiktion schienen eine beängstigende Symbiose einzugehen. Und die Analyse des lange als vorbildlich geltenden „Wohlfahrtstaates“ kann natürlich aufgrund der dürftigen Vergangenheitsbewältigung der Olof Palme-Periode noch weiter betrieben werden. Grandios jedenfalls, wie Larsson hier einen alteingesessenen Familien-Clan vorführt, der sich in bester Ibsen-Tradition mit einer Lebenslüge über Wasser hält. Und wie er gleichzeitig all die Heavy-Duty-Gesellschafts-Probleme in die Trilogie einbaut, ohne den Roman damit zu überlasten. Aufklärung vom Feinsten – the real Hot Stuff !!!

Big Money und die Illusion vom American Dream

Nun also zu Trilogie Nummer zwei: Nach The 42nd Parallel von 1930 und 1919 von 1932 erschien 1936 der letzte Band The Big Money, den man getrost als John Dos Passos’ Abrechnung mit der Illusion vom American Dream sehen kann. Fast als Leitmotiv hatte er seiner Trilogie schon in der Einleitung die Behauptung vorangestellt: „USA, das ist eine Handvoll Beteiligungsgesellschaften, ein Häufchen Gewerkschaften, ein in Kalbsleder gebundenes Gesetzbuch.“ Die Sehnsucht nach einem aufgeblasenen Sozialprestige, hedonistischen Exzessen und schnellem Geld hatte Dos Passos (1896-1970) zwar schon in Manhattan Transfer thematisiert, aber die Hektik der rund hundert Figuren, die meistens auf der Suche sind – nach Arbeit, Wohnung, Kohle oder einer schnellen Affäre – verhinderte eine Konzentration des Erzählers auf einige wenige Figuren. In The Big Money stehen dagegen einzelne Figuren wie Charley Anderson, Mary French , Margo Dowling u.a. im Mittelpunkt, deren Traum vom schnellen Geld, einem hochprozentigen Speak-Easy-Abend oder einem Techtelmechtel sich vor uns entfaltet. Kriegsheimkehrer Charley Anderson ist eigentlich ein Held, der sich an der Front als Krankenwagenfahrer um Schwerverletzte kümmerte. Doch er ist nach der Rückkehr in seine Familie auch irgendwie aus der Bahn geraten: Als Autohändler (ausgerechnet für Ford!) will er seinen Bruder auf keinen Fall unterstützen, obwohl er sehr Technik-affin ist. So lässt er sich treiben, springt auf die Spekulationswelle auf und sieht sich schon als betuchter Erfinder oder Börsenspekulant, bevor er überhaupt eine konkrete Erfindung wie den geplanten elektrischen Anlasser für einen neuen Flugzeugmotor zum Patent angemeldet oder an der Börse versilbert hat: Das Fell des Bären zu verteilen, bevor der überhaupt erlegt wurde, das scheint für Dos Passos das Kernproblem dieser Träumer zu sein. Sie bejubeln sich selbst, prahlen mit ihrem demnächst fälligen Dollar-Segen und beeindrucken damit ihre staunenden Freundinnen. Doch ihre Visionen, Beziehungen, Pläne und Strategien sind brüchig und ziemlich situationsabhängig: Für einen unterhaltsamen Abend lassen sie ihre seriösen Vorhaben sausen und lassen sich etwa – wie etwa der betrunkene Charley in seinem Stutz-Sportwagen – auf ein Rennen gegen die Eisenbahn ein, was zu einem Unfall führt und mit seinem Exitus endet.

Die sensible, sozial engagierte und immer hilfsbereite Mary French stellt dagegen den maximalen Kontrast dar: Das College verlässt sie, um ihrem Vater während der grassierenden Grippewelle in der Praxis zu helfen, während ihre Mutter an nichts Anderes denkt als an Profitmaximierung, die dem allzu gütigen Doc nicht gelingt, weil der seinen hippokratischen Eid ernst nimmt und allen hilft – auch den völlig Verarmten.

Dos Passos hat in der Trilogie seine in Manhattan Transfer eingesetzte Wochenschau-Technik fortgesetzt, die er hier noch Promi-Porträts über erfolgreiche Erfinder und Unternehmer (Edison, Ford, Hearst usw.) anreichert, die seine große Kunst zeigen. Der skrupellose Zeitungs-Zar Hearst wird als Kriegs-Profiteur und „Poor Little Rich Boy“ verhöhnt, der immer auf der Suche nach Sensationen oder Kunst-Raritäten ist. Henry Ford erleben wir als seelenlosen Automaten, dessen Synapsen offenbar wie ein Fließband konstruiert sind, Edison wird als eher konfuses, unter Strom stehendes Genie gezeigt, das sich völlig verzettelt hat beim Planen immer neuer Projekte. Diese Mosaiksteinchen sollen ein irritierendes Gesamtbild ergeben, das wir erstmal genauer betrachten müssen, bevor wir entrüstet protestieren. Denn was Dos Passos in seiner Trilogie vor uns entfaltet und zu analysieren versucht, ist eine tragische Kluft, die nicht nur Arm und Reich teilt, sondern auch die demokratische Basis der Gesellschaft gefährdet. Das alles beschreibt der große Erzähler ohne den Oberlehrer mit erhobenem Zeigefinger zu geben: Mit großer Empathie für die Underdogs und eiskalter Ablehnung gegenüber liquiden Schaumschlägern und menschenverachtenden Egomanen.

Das Eintauchen in diese Trilogien war jedenfalls auch im Lockdown ein Hochgenuss!

Die Texte von Peter Münder bei uns hier.

Andrew Nette

John le Carre, my 2020 and The Looking Glass War

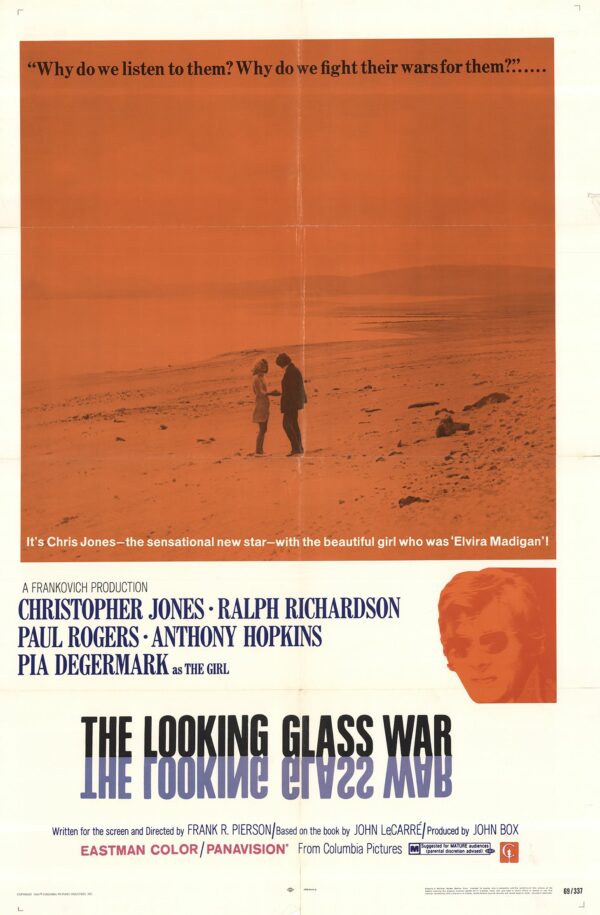

It is fitting that my last post on this site for 2020 is a short tribute to the passing of a writer who has given me an enormous amount of pleasure during this difficult year, David John Moore Cornwell or as he is better known, John le Carré. Since his death on December 12, a sea of ink has been spilt on le Carré’s influence on the spy novel and his undoubted merits as a writer. I don’t intend to go over this territory again. Instead, I want to briefly discuss what it is about his George Smiley series I have found so fascinating. I also want to talk about one of the films based on his work that I believe does not get nearly enough praise, Frank R Pierson’s 1970 adaptation of le Carré’s 1965 novel, The Looking Glass War.

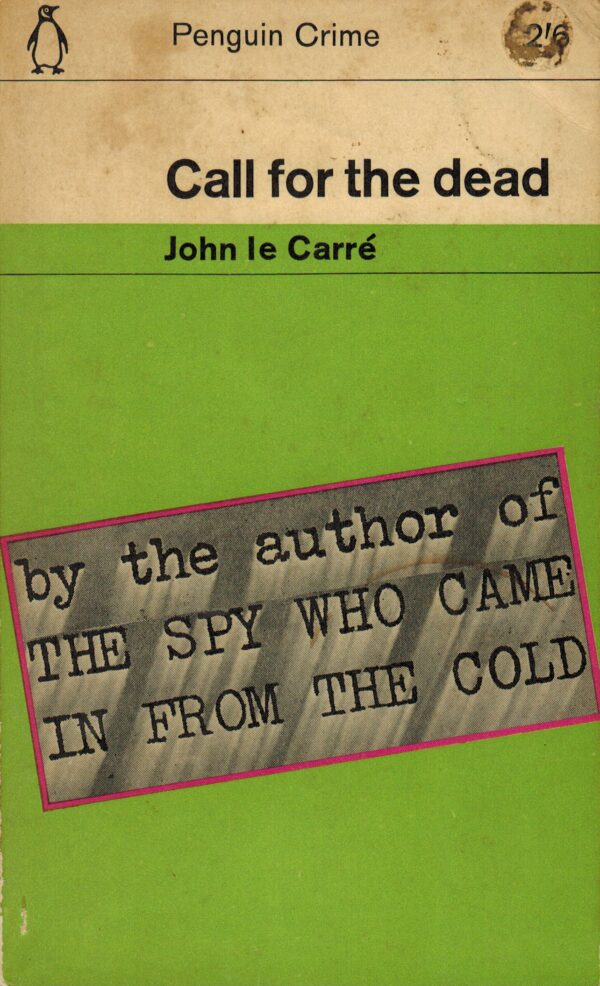

Melbourne, the city I live in, spent the better part of 2020 in hard lockdown in response to the Covid 19 virus. Reading was one of my many responses to suddenly finding myself with more free time. One very wet, cold Saturday morning at the outset of winter I picked up a paperback I bought ages ago – I can’t even remember when and where – the 1964 Penguin Crime edition of Call for the Dead. Originally published in 1961, it was the author’s first novel, an unrelenting grim hybrid mystery/espionage story in which a young (but in some respects quite old) George Smiley investigates the unusual death of an otherwise unremarkable British civil servant.

I had read what is probably le Carré’s best known work, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, years ago and remember liking it a lot. I enjoyed Call for the Dead so much that I decided to work through the other entries in the Smiley series. 2020 saw me get through, in order, The Looking Glass War, The Honourable Schoolboy and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. A Murder of Quality, Smiley’s People and The Secret Pilgrim will have to wait for 2021. Apart from the fact that le Carré has such a wonderful prose style and his power of description, there are three things I love about the Smiley novels.

First, they really as noir as hell. More about that later.

Second, I adored the slow, analogue nature of spycraft as it is depicted in the stories. With the exception of The Secret Pilgrim, all the Smiley books were written in the 1960s and 1970s, at the height of the first Cold War. Of course, looking back now, so much was going on but, on another level, events moved much slower than now. The geo-political conflict between the West and the Communist Block was in a kind of stasis, almost as if it was trapped in amber. And pre-Internet and modern telecommunications, our level of knowledge about what was happening in the Soviet Block was so limited. Connie Sachs, one of le Carre’s best characters, could spend a month just analysing a photograph of Russian dignitaries at a May Day parade. There is a terrific section in The Honourary Schoolboy in which journalist cum spy, Jerry Westerby, is trying to track down a missing Air America pilot called Ricardo. To do so he has to physically travel to Laos, Saigon, Phnom Penh and, finally, north east Thailand. There are numerous other examples. It is a world that is so different to the one we are in now and, to be honest, part of me misses it.

Third, in a strange way, these books chronicle my father’s generation, a group of men both damaged & strangely sustained by WWII and the Cold War that followed. Men who had had hard lives, took solace in alcohol, and were in many respects emotionally limited. Most of all, they were men for whom the war and their part in it, good or bad, was the defining point of their lives, certainly something that defined everything that followed.

Anyway, 2020 also saw me revisit several of the film adaptations of Le Carre’s Smiley books. I re-watched The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963), Sidney Lumet’s version of Call for the Dead, The Deadly Affair(1967), the 2011 film version of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, and the 2018 television series, The Little Drummer Girl, all of which are excellent in their own way.

But the screen adaptation I most enjoy, and the one of le Carré’s work that seems to get the least appreciation, is The Looking Glass War. The film is quite different to the book. To cite one example, Smiley makes a small appearance in the book but is completely absent in the film. Nonetheless, for me, this movie is a near perfect distillation of the reasons why I enjoy le Carré’s work so much.

The Looking Glass Warconcerns the Department, a low rent version of Smiley’s Circus, headed up by a man called Leclerc (Ralph Richardson). Leclerc believes he may have stumbled across a plan by Moscow to base missiles on East German soil, if so a major escalation of the Cold War. But all he has in the way of evidence are some very grainy, indistinct photographs sent to him by a contact on the Soviet side of the divided German border. In order to get more detail, he pays a commercial airline pilot to fake accidently encroaching Soviet air space and take photographs, an incredible dangerous ploy given the tensions over the border between the divided Germany. But the agent receiving the photographs is killed. Or not. It is unclear whether the agent concerned was the subject of a political murdered or the unfortunate victim of a hit and run driver.

What should we do to get more information, asks the risk adverse Under Secretary of State, (Ray McAnally)? “If this were the war, we’d put a man over the border,” replies Leclerc. “It required nerves and money. In those days we had both.” Leclerc gets the reluctant agreement of his political masters to do just that. Now all he needs to do is find the right man for the job. A potential candidate emerges in the form of Leiser (Christopher Jones), a swaggering, louche, nihilistic but charismatic young Polish man who has been detained by the British authorities after jumping ship in London to visit his pregnant girlfriend (Susan George). Leclerc makes Leiser an offer, do “a little job” for the Department in return for being able to stay in the UK permanently.

Leclerc assigns the Pole a minder, Avery (Anthony Hopkins), an idealistic somewhat fragile young man dealing with a failing marriage. Next Leiser is sent to a safehouse for a crash course in spy craft, something at which he has mixed success. While his overconfidence is a problem, Leiser’s time living in a police state has imbued him with a deep mistrust of everything, making him a natural survivor. As one of his trainer’s quips, he also the “morals of a bitch in heat”.

At one point, Leiser escapes the safe house to visit his girlfriend, only to discover she has had an abortion. Angry, he decides to go ahead with the mission anyway and is secreted over the border with orders to make contact with the man who sent Leclerc the photographs and get more information. While crossing into East Germany, however, Leiser kills a border guard, alerting the secret police to his presence and pitting him in a race against time to complete his mission before he is apprehended.

The Looking Glass War is arguably Le Carre’s bleakest novel and the film is saturated in a distinct noir sensibility. While the West and the Soviets engage in a brutal, no holds barred battle for supremacy – fought out on the ground by disposable proxies such as Leiser – what seems like the inevitability of nuclear war infuses every interaction with paranoia and futility. Meanwhile, in stark contrast to the stakes involved in this battle, is the penny pinching and bureaucratic arse covering that characterises the actions of Leclerc’s political masters.

“It is just like the old days” comments Leclerc with glee, as he and Avery wait for Leiser to make contact. Leclerc is defined by his experience as an intelligence operative during World War II. It is his career highlight and the touchstone of his identity, and he constantly refers to it to guide how the Department should proceed in the new Cold War, even though it is a totally different, much less morally certain conflict.

Pierson scripted films like Cool Hand Luke (1967), The Anderson Tapes (1971) Dog Day Afternoon(1975), but The Looking Glass War was his first outing as a director. I do not want to give away the ending for those who have not seen it, but the other aspect of The Looking Glass War I love is how Pierson handles the second half of the story. While Leclerc and Avery wait for word from the agent, Leiser is forced to lie and murder to survive. At the same time, the dark espionage themes are accompanied by a remarkable tonal shift, the introduction of an almost European art house feel and aesthetic as Leiser makes his way through the largely deserted German countryside (the entire film was shot in Britain with some stunning cinematography by Austin Dempster) and falls in with an unattached, unnamed woman (Pia Degermark) and a young boy.

Richardson is great, as always. Hopkins pulls off the role of spy well, a fact reconfirmed a year later when he starred in 1971 film version of Alistair Mclean’s When Eight Bells Toll. The other highlights are the presence of Jones and Degermarkn, two ‘it’ actors of late 1960s counter counter culture infused cinema, both of whom had real presence but who only starred in a handful of films before quitting acting. After a series of torrid affairs, including one with Degermarkn who he had previously appeared with in A Brief Season (1969), Jones had a breakdown and quit acting, He re-emerged in Los Angeles Sunset Strip counterculture drug scene, then became an artist and died in 2014. Swedish born Degermark had a similarly tumultuous life and after her brief stint as an actress, suffered from anorexia and did jail time for fraud.

Andrew Nette lives in Melbourne and is a writer of fiction and non-fiction, reviewer and pulp scholar. He is the author of two novels, Ghost Money,a crime story set in Cambodia in the mid-nineties, and Gunshine State, and co-editor of Hard Labour, an anthology of Australian short crime fiction, and LEE, an anthology of fiction inspired by American cinema icon, Lee Marvin. He also co-edited Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980, and Sticking it to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1956 to 1980, both published by PM Press. Both reviewed by Alf Mayer here and here. He is co-editing a third volume for PM Press, Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950-1980. His articles with us.

Twitter: @Pulpcurry

His blog Pulpcurry

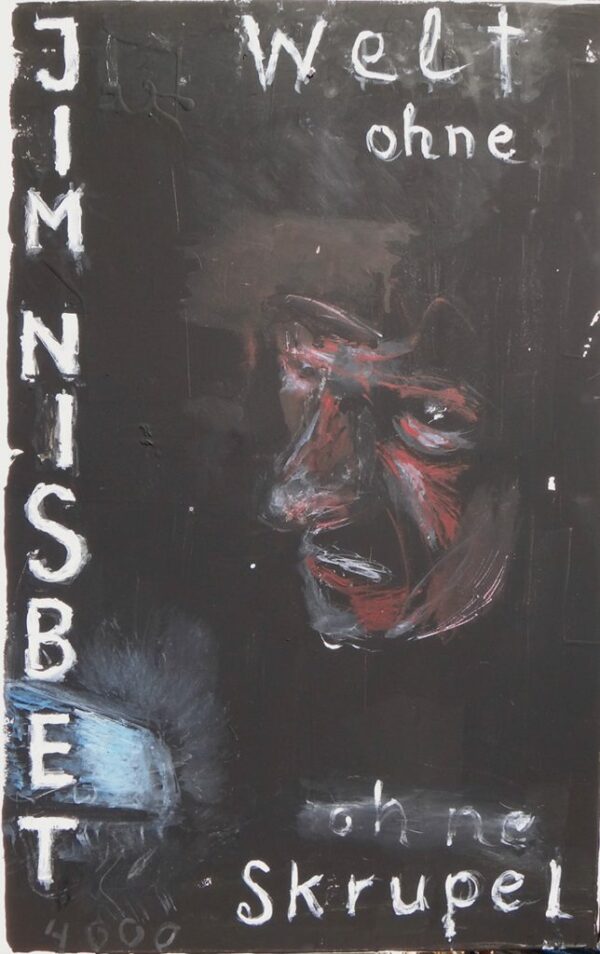

Jim Nisbet

When the people spend every waking hour on politics, the people are not well. When politics is as far down the queue of vital interest as, say, the satisfactory resolution of a residential plumbing problem two blocks over, the people are happy.

Surely, that’s somewhere in the I Ching.

Culture-wise, however (remember culture?), 2020 started off with a bang, in January, with Eddie Mueller’s Noir City Film Festival. Founded in San Francisco in 2003 and, pre-COVID at least, spread to some six or seven additional cities, Noir City annually presents ten days of noir double features, sometimes four separate movies a day, with a few re-screenings of selected morsels, and the fans flock. Period cosplayers, experts, authors, auteurs, critics, cinephiles, cineastes, booksellers, poster vendors, a hat maker and the press throng the lobby of the famed 1400 seat Castro Theater, the smell of fresh popcorn suffuses the air, die-hards camp out for days in the balcony, there’s a line out the door and up the sidewalk for every show, and during every show the lobby is completely deserted.

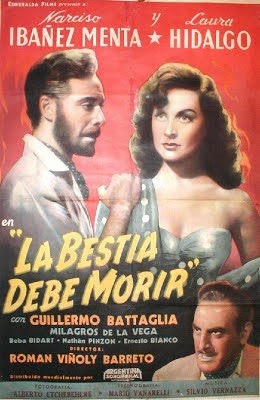

There’s no way to go into 2020’s full program here, though film buffs will find a Googoolysis well worth pursuing, but this year’s festival opener was an Argentinian curiosity called La Bestia Debe Morir. The film is killer, and so is the back story.

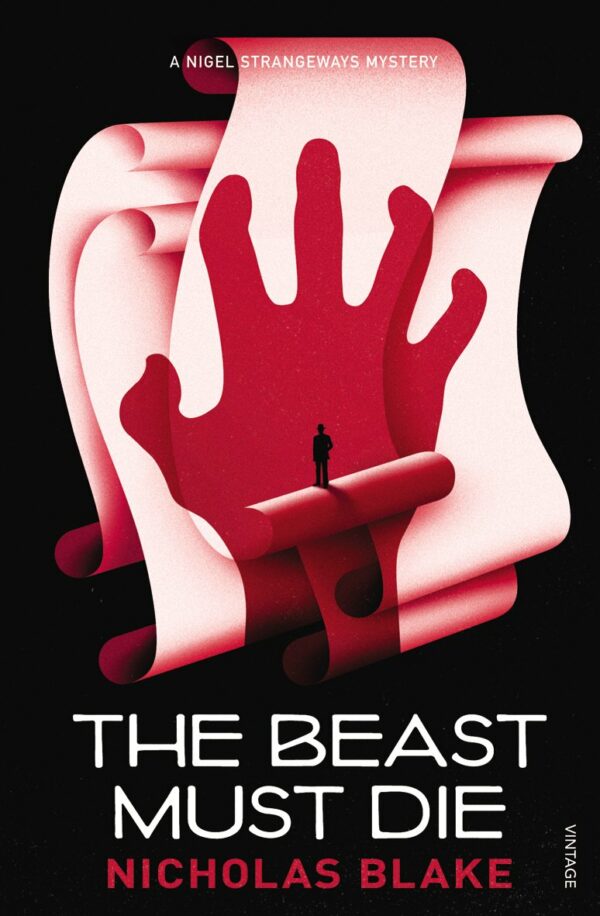

In 1938 one Nicolas Blake published a thriller called The Beast Must Die, featuring the recurring character Nigel Strangeways, an amateur sleuth who figured in some sixteen similar novels.

So far so genre-normal, you might say. But…

Jumping into the backstory almost at random, Nicolas Blake turns out to have been the pseudonym of one Cecil Day-Lewis, a poet who, in his early days, earned his crust by cranking out detective fiction. Down the road (1957), he fathered the actor Daniel Day-Lewis. Further down the road (1968-1972), Cecil Day-Lewis became the Poet Laureate of England.

Readers of this publication will almost certainly be aware that, in 1969, the French director Claude Chabrol lensed Que la bête meure, and, indeed, this film, too, was based on the Blake novel. I myself saw the film in the 70s and, frankly, despite seeing it in an actual theater, I don’t remember it, but, if I did remember it, I would almost certainly have to declare it inferior to its antipodal cousin. Doesn’t that sound just like a critic on bourbon?

Noir City curator and host Eddie Mueller, aka The Czar of Noir, also runs a thing called the Film Noir Foundation, whose mission is to ferret out ignored, forgotten and/or endangered films and rescue them, often by undertaking expensive, painstaking restorations. Case in point: La Bestia Debe Morir.

Filmed in Argentina in 1952, the movie is nothing if not an apotheosis of film noir. It’s got it all — incredible cinematography, with all the tricks beloved of the genre: high-contrast black and white, low angles when it counts, tight closeups in moments of passionate dialogue, an excellent script, even a fog-beshrouded waterfront — along with a breakneck plot, twists, turns, bathos, pathos, a score to go with them, a sadistic and degueulasse self-made rich guy, his femme-fatal sister-in-law tortured by a horrible secret, a ridiculous coincidence or two, first-person narration, a flashback of such length and intensity that you forget you’re in it, an incriminating diary, an all-hands-on deck living-room showdown-reveal, and knock-out performances, including an over-the-top death-by-poison scene that, at the Castro at least, garnered audience enthusiasm sufficient to drown out the subsequent sixty seconds of dialogue.

Here’s the plot. One night the lead character, a successful writer of detective thrillers and, key, a widower, sends his beloved only son to the local bodega for cigarettes— a short walk through a deserted village. On the way home, the kid is greased by a hit-and-run driver, leaving the father to discover the body. The first lines of the novel (I have it right here) launch the story: “I am going to kill a man. I don’t know his name, I don’t know where he lives, I have no idea what he looks like. But I am going to find him and kill him…”

There are of course this and that cinematographic missteps. The novelist/narrator dominates the movie, and by the time the Nigel Strangeways character is introduced, on top of a couple of local cops, excepting the triviality that the resolution pretty much mandates such a guy at this particular point, the amateur sleuth is virtually superfluous; in spite of which the film ends with a dark and delicious moral ambiguity and, bonus, the all-characters-on-deck living-room reveal isn’t the end of the movie.

The star of the film, Narcisco Ibáñez Menta, also wrote the script, and his standout performance was apparently preceded by a long and successful career in horror movies.

But here’s a story about this movie that I particularly like. The single known copy of La Bestia Debe Morir was only recently discovered, in Argentina, by a curator at the national film archive. An exhibition print, the stock was in very bad shape and, without considerable and expert attention, seemed destined to be lost forever. Somehow this guy got in touch with the Film Noir Foundation, and eventually the reels were shipped to an expert in Los Angeles, after which the verdict came down: the film could be restored, it would be an expensive and time- consuming process involving not one but two labs, and it needed to happen sooner than later.

Though the FNF was some $50,000 short of the cash necessary to the task, Mueller okayed the deal and the restoration commenced, leaving the Czar of Noir to go looking for the money.

But wait: the deal done, word came from Argentina that, inexplicably, all Argentinian movies in world-wide circulation in their original or unique format needed to be remanded to the mother country within sixty days, else severe penalties would fall upon the head of whomever sent the property offshore in the first place. Why and how this came about, I’m not in a position to explain, but it presented a serious kink to the restoration plan. Mueller and his foundation were on the hook for the money, the Argentinian middleman was on the hook for the print, and the continued existence of a unique work of art lay in the balance. Yet, the reels had to be shipped home. What to do?

Well, as our man in Argentinia pointed out, when the reels left the country, the celluloid was in such bad shape it couldn’t be screened; there wasn’t enough intact footage to even thread it through a projector; it’s only by virtue of the labels on the film cans that we know what they contain. Get it? Wink wink?

In due course, and before the deadline, nine cans of coagulated celluloid arrived in Argentina to be checked into the national cultural repository under Bestia Debe Morir, La, and the culture soldiered on.

A year or two later, San Francisco’s Castro Theater hosted the North American premier of a beautifully restored print of La Bestia Debe Morir, complete with English subtitles.

No politics mentioned. How about that?

Jim Nisbet, Jahrgang 1947, ist Autor von dreizehn Romanen und mehreren Lyrik-Bänden. In den letzten vierzig Jahren veröffentlichte er darüber hinaus diverse Artikel, Essays und Shortstorys in Zeitungen, Zeitschriften und Anthologien sowie ein Sachbuch über Bau und Design retro-futuristischer Möbel. Er lebt in San Francisco. Seine Romane bei Pulpmaster.