Expect the unexpected

Expect the unexpected

Isabella Thermes about mourning her parents and finding solace in her work

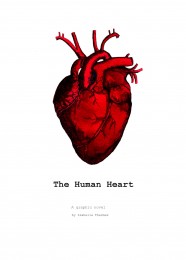

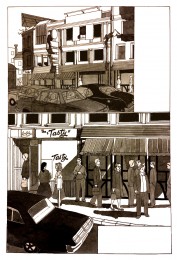

Arthur Sinclair, the protagonist of my graphic novel, made his first appearance on page in the summer of 2014. Back then, I made the decision and the bold move of leaving London, my home of 11 years and the place where I ultimately had a lot of fun working as a literary agent, to venture to Berlin.

That summer marked the beginning of a long „sabbatical“ that I used to outline this project, learn German and lay the foundations for a new career as illustrator. But, after learning about my mom’s illness – she was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia in the summer of 2016 –, everything came to a halt, sudden, constant worries grabbing me by the throat.

After having earned a precious feedback from Igort (prominent graphic novelist in Europe and founder of Fandango e Coconino Press, among the best independent graphic novel publishing houses in Italy) with the first draft of my graphic novel, I put the project into a drawer without wanting to ever look at it again: it was too big, it required extensive work and my head simply was not in the right place

I was not prepared to see my mother going.

‚Not just yet‘, was all I kept on repeating myself every day from that 2016 summer on.

‚Not just yet‘, the constant thought that filled my days.

Back then, ’not just yet‘ was the hope, the resilience that motivated my quixotic search for a cure.

Last year, in mid December, after much travelling back and forth, I again packed a small bag to visit my parents. Determined to find the home assistance that would help them cope with their situation when I was unable to be there, I set a bullet-point list in my head, my heart pounding in my chest with anxiety. When I reached their home late at night, however, I found that none of my plans were going to make any sense. My mom’s illness had already altered her features, after a month of constant fever she was too weak to even get up and greet me.

My father could not meet my gaze without tears welling up in his eyes.

I felt a pang and knot in my throat, though I knew I had no other choice than to go on playing the brave, optimist role.

The morning after my arrival, my dad called himself an ambulance. A serious heart issue, we learned, confined him to the hospital.

A week later, I had to call an ambulance for my mother, whose fever rose so high, I couldn’t even get her to accept a draught of water.

From that point on, my life spun into a whirlwind that quickly morphed into a hurricane, bouncing between two different hospital departments and floors, terrible truths I had to hear and immediately transform into plausible lies. I was caught between a hospital that wanted to get rid of them, because of the shortage of beds and personnel, and the frightening option of having both of them sick at home without proper medical assistance. My present swayed between this reality and the cold limbo their big, gloomy and empty house had become, their everyday objects laid everywhere, as if their absence were only a temporary occurrence. My head floated in that murky environment like a small, fragile boat, skirting numbly their spaces and heading straight towards what used to be my bedroom. A half benzodiazepine pill separated me from that hospital mayhem and the stygian nothingness I yearned for and into which I plunged every night. That haze allowed me to erase, as if on tape, each day I had lived, on order to record something new on the next.

Fast forward to three weeks later, the saddest Christmas and the darkest New Year’s Eve. My mother sent me away to join some friends for dinner, fireworks merrily cracking through her room’s large windows, while I was unwilling and guilty to leave her there. One more week of agony for her, carrying alone the burden of that suffering, while I, the powerless spectator, could do nothing but endure that pain while it lasted. Of the night of January the 7th of 2018, I remember only the blue, flourescent light in the silent, white, aseptic hospital corridor, and her irregular breathing.

The morphine, when all else was finally left behind, her restless eyes now permanently closed, her brow knitted in pain, the drip-feeds on the tripod next to her bed, her arms and legs abnormally swollen, the urine sack the colour of burgundy wine. Just when I was asking myself how would I react if she stopped breathing, her intakes of air became irregular.

The morphine, when all else was finally left behind, her restless eyes now permanently closed, her brow knitted in pain, the drip-feeds on the tripod next to her bed, her arms and legs abnormally swollen, the urine sack the colour of burgundy wine. Just when I was asking myself how would I react if she stopped breathing, her intakes of air became irregular.

„I think she is going“, said a friend who was keeping me company.

I kept on holding her hand, a Rosary clutched in the other. Then her breathing stopped.

It was one o’clock at night.

„Call the doctor and the nurses“, I heard.

My head swam. I ran out into the corridor to call them. When they entered the room, they sent us out.

A minute was all it took to make a world of difference. A minute later I understood what I refused to accept. I only wanted to scream out my despair on top of my lungs. My mother, my confidante, my preferred travelling companion, the person I entirely trusted and loved the most, was gone.

I was too shocked and overwhelmed to even feel pain.

I was too confused to consciously pick, in a closet full of many elegant options, the right clothing for her burial, something that had to be done immediately after her death. I walked through her funeral with that marvellous opiate calmness that only sedatives could give in a circumstance like that, red lipstick and radiant skin to honour the way she had always been: a really bright red lipstick was her signature, she could pull it off so well that without it, her face lacked colour.

Her funeral was packed with people: a beloved teacher, a beloved friend, a beloved human being. A classy lady, a compassionate, generous, wise, thoroughly good human being. It made me think of how truly accomplished her life had been in all respects.

I felt so proud. I wished I could share this pride with her, but of course it was impossible, since she, as the protagonist there, was locked into a coffin surrounded by simple flower arrangements. I sat on the first church bench, stunned, as if I were participating in someone else’s funeral. Next to me was the empty space that my dad would have occupied, but of course he was still in hospital. I had strong recommendations from the doctors to not tell him anything. However, on the afternoon of my mom’s funeral, he suddenly closed his eyes and stopped drinking and eating. He wouldn’t respond to any stimulus, to any voice. His condition had suddenly, inexplicably worsened.

The doctors were baffled. On January the 10th, I left his room after having spent an hour talking in vain to him, the lively banter we’ve always had. It was 8pm.

A few hours later, my mobile rang as I was getting into bed, my half benzodiazepine pill ritual fulfilled. The hospital called, it was extremely urgent, I needed to get there as fast as I could, my dad was passing away. I burst into tears, shaking uncontrollably, unable to speak, grabbed some clothing from a chair and frantically looked for a cab.It was foggy and chilly outside, one of the coldest winters to date there: one of the many anomalies in an already unprecedented picture. I gave the driver directions to the fastest shortcut, ran once more towards the elevators, charged through the doors. Outside his room were a nurse, the doctor and my father’s „room companion“, a kind man who was hospitalised with him. Their faces were gently alight with that absurd, paradoxical truth.

A few hours later, my mobile rang as I was getting into bed, my half benzodiazepine pill ritual fulfilled. The hospital called, it was extremely urgent, I needed to get there as fast as I could, my dad was passing away. I burst into tears, shaking uncontrollably, unable to speak, grabbed some clothing from a chair and frantically looked for a cab.It was foggy and chilly outside, one of the coldest winters to date there: one of the many anomalies in an already unprecedented picture. I gave the driver directions to the fastest shortcut, ran once more towards the elevators, charged through the doors. Outside his room were a nurse, the doctor and my father’s „room companion“, a kind man who was hospitalised with him. Their faces were gently alight with that absurd, paradoxical truth.

My father had just died. It was one o’clock.

I sat by his bed, softly speaking to him, holding his already cold hand. During the almost four weeks in hospital he seemed to have shrunk, his face sad and pained. My heart was drenched in regret, heavy with the misunderstandings that had often underlined our turbulent relationship.

I sent a couple of messages, messages in a bottle, S.O.S, hoping that someone among the few good relatives or friends left would receive them, be there, next to me, because it was just too much, and my whole being was collapsing. Within a span of 48 hours, I was again at the morgue, bewildered in front of his coffin and his remains in a suit, tie, socks, shoes that now looked too big on him, the clothing that my cousin had helped me put together in a hurry.

Then, another funeral, and me, sitting on another church’s front row bench. This time, no empty space for dad next to me, his place instead was in the coffin before me. I showed the same serene, benzodiazepines‘ face, same red lipstick, as I greeted the silent, weeping procession of friends, relatives, colleagues, acquaintances, neighbours. I told myself I could hold it together this time too, but the need to let it all go was overpowering. And finally, I broke down in tears, those tears I had held in for a month. Tears for both of them, tears for myself, tears because, even though this was the best solution possible in the worst case scenario, they were no longer there. I felt like I was walking through earthquake rubbles, dust not yet settled, maundering like a shell-shocked, half-demented human being.

Within a span of 48 hours, I had no family to ever return to.

Some months and many sedatives later, the Italian bureaucracy and its procedures related to my parents‘ death forced me to venture through the debris. In the middle of that bureaucratic nightmare, two illustration projects shone their feeble, consoling light, reopening that long barred window to a happier world. And the thought of Arthur Sinclair and that graphic novel kept in the drawer came back to me.

Some months and many sedatives later, the Italian bureaucracy and its procedures related to my parents‘ death forced me to venture through the debris. In the middle of that bureaucratic nightmare, two illustration projects shone their feeble, consoling light, reopening that long barred window to a happier world. And the thought of Arthur Sinclair and that graphic novel kept in the drawer came back to me.

„You really need to get your head around it and complete it. What’s the point of keeping unfinished projects in a drawer?“, said my mother before becoming too ill to speak. Her words made even more sense after she was gone. Their loss, so big, was the hole in my heart which brought that story to completion. Though I initially had no desire and no energy to look at the painstaking work of finessing pages of detailed backgrounds („the space where the protagonists live and move, the space that tells a story in its own right“, Igort had said), once back in Berlin, I opened that drawer again.

I had to feel for the story’s pulse.

To reach that pulse, I had to undergo a cumbersome, laborious process, removing the rust from my brain down to my joints and on to my fingers, and then, at last, finding that flow again. Without minimizing a state of perpetual physical and mental exhaustion, I began to reimagine, reconfigure, redraw pages. And so, the initial thought of simply integrating new sections into the existing story, „fleshing out“ the characters, became a whole new approach to the narrative instead.

Told and broken down to infinitely richer images, I reached out for the protagonists: Gaya Clark, a student completing her doctorate at King’s College in London, Oliver T. Edwards, a retired English Physics professor that went from Oxford to MIT, his wife, the American Vera Kendall, the beguiling Mr Sweeney, maverick, investor-extraordinaire and the melancholic, laconic, mysterious Anatolij Stanislavskij. And last, but not least, Arthur Sinclair, the thread that joined these lives and stories together in a most surprising way.

Told and broken down to infinitely richer images, I reached out for the protagonists: Gaya Clark, a student completing her doctorate at King’s College in London, Oliver T. Edwards, a retired English Physics professor that went from Oxford to MIT, his wife, the American Vera Kendall, the beguiling Mr Sweeney, maverick, investor-extraordinaire and the melancholic, laconic, mysterious Anatolij Stanislavskij. And last, but not least, Arthur Sinclair, the thread that joined these lives and stories together in a most surprising way.

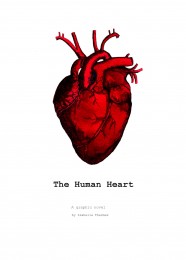

The title, ‚The Human Heart‘, had been decided upon since the first draft along with the cover illustration (an old anatomy drawing of the human heart) that much to my chagrin, became widespread shortly after I had outlined my project.

The story was born and intended as an exploration of loss and grief from a magical realism perspective. The theme is harsh, punchingly hard where it hurts most, the magical realism there to shift the narrative to a level where the pain and grief that accompanies loss becomes more… tolerable. After my own, very intense experience of grief and loss, this story became the place where I could put a little of my mom, dad, myself, and spread the remaining, undecipherable feelings into other characters, along with their features, melted and molded into random people and friends.

Spanning from Moscow in the late 50s, early 60s, continuing between East Berlin and then West Berlin in the year 1965, it travels to Boston in the years from 1967 to 1969 and beyond to reach London in 2014. To each protagonist a city and its timeframe, with Arthur Sinclair as the perennial wanderer, the man who crosses time and places, travelling the landscape of dreams, dutifully collecting hearts on behalf of Sweeney’s, because the human heart is the precious place where memories, feelings, ideas, intuitions are formed and developed; because the human heart is the most precious treasure’s chest.

And the human heart is the most coveted prize, the core to Sweeney’s ambitious project: a perfect world, where order is restored over the chaos of human feelings. Sweeney’s world is the flight of fancy, a futuristic place where mute, strange collaborators operate in a sterile environment, oblivious to the whirring, omnipresent cameras achieving the goal of incessant surveillance and control.

And the human heart is the most coveted prize, the core to Sweeney’s ambitious project: a perfect world, where order is restored over the chaos of human feelings. Sweeney’s world is the flight of fancy, a futuristic place where mute, strange collaborators operate in a sterile environment, oblivious to the whirring, omnipresent cameras achieving the goal of incessant surveillance and control.

Entirely drawn with rapidograph pens, my preferred drawing tool since the childhood evenings spent next to my dad’s technical drawing table, this story is also, my tribute to the two people who made it possible.

Isabella Thermes: Born in Italy, a literary agent by trade, Isabella Thermes has lived and worked in the US and in London. She currently lives and works in Berlin, where she is pursuing a career as illustrator. The Human Heart is her debut graphic novel. Her new website is her next plan. In the meantime, some of her most recent work can be seen on Behance while her first attempts to storytelling and drawing can be seen on: https://isabellathermes.com and here.

© 2018 All images and content copyright Isabella Thermes