The story-telling wars

by Christopher G. Moore

Fires, floods, volcanoes, dying sea coral, boats, dogs, rivers, deaths, births, anniversaries, weddings, car crashes—help us as we can’t absorb all of this information—this is a daily timeline on Facebook or Twitter. Many of us have that feeling of being submerged over our heads in information. We are losing touch to distinguish stories that signal catastrophic consequences from what are the normal drift of life.

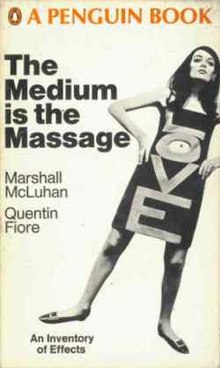

We are vulnerable to images of dogs, cats, children, or seductive smiles—the online visuals grab us and pull us in. We click on the story. It’s like picking up a book in a bookstore (remember those?) where opening the book and reading a page or two was the halfway to deciding whether to buy it. Your worldview is made from, shaped and reinforced by these stories. The medium in which the story appears is as important as the actual story. As Marshal McLuhan famously said in 1964, “The medium is the message.”

The oral story teller required a physically present audience. His or her voice was the medium. Guttenberg changed all of that with the printing press in 1439 which spread throughout Europe over the next sixty years. The medium became the pamphlet, newspaper or book. The audience didn’t have to gather to listen to the author tell his or her story. But that time has changed. The volume of stories makes selecting which ones to read crucial. We have to choose what to ignore and what to pay attention to. Books were revolutionary. You could read one at your own time and place of convenience. if Gutenberg had gone the Mark Zuckerberg routine of Facebook and created a story-telling platform cartel. Today would be a very different place as people’s reality would be stamped with Gutenberg’s values at every level of society, politics and religion.

The oral story teller required a physically present audience. His or her voice was the medium. Guttenberg changed all of that with the printing press in 1439 which spread throughout Europe over the next sixty years. The medium became the pamphlet, newspaper or book. The audience didn’t have to gather to listen to the author tell his or her story. But that time has changed. The volume of stories makes selecting which ones to read crucial. We have to choose what to ignore and what to pay attention to. Books were revolutionary. You could read one at your own time and place of convenience. if Gutenberg had gone the Mark Zuckerberg routine of Facebook and created a story-telling platform cartel. Today would be a very different place as people’s reality would be stamped with Gutenberg’s values at every level of society, politics and religion.

In the digital revolution, the new medium has centralized the machinery of story-telling into the hands of a very few. Mark Zuckerberg, Rupert Murdoch and Jeff Bezo are a few of the digital heirs to Gutenberg who have discovered great wealth and influence by developing and owing the digital story-telling platforms. Facebook has monetarized hate as in the case of Burma. To close down an audience is to lose money if you are building an online community. For years, Facebook has looked the other way, or underfunded and understaffed a way to actually look at how Burmese bigots and radicals, in and out of country, used Facebook to build an audience with tell stories that demeaned and dehumanized the Rohingya and justified their expulsion and genocide. The recent suspension of Alex Jones and his InfoWars with his conspiracy theories, drawing an audience in the millions, was said to glorify violence, promotes hate speech, and dehumanize Muslims, transgender and immigrants. YouTube, Twitter, Apple and Spotify followed Facebook’s lead and sent Alex Jones packing.

These events suggest it is time to re-examine the information content in stories, the medium of story-telling, the role of story-tellers and the chaotic transition of story-telling traditions as story tellers and audience adjust to story gorging on various digital platform.

We have two general models of story-telling. One is ancient. One is new. It is only a matter before they collide. Some might say we are witnessing the shock waves of that collision with a populist shock wave spread across the globe. I’m a professional story-teller which means I have a dog in this race. The reality is that we are all story-tellers with an audience, as we are part of an audience for other story-tellers. We make sense of our lives by telling stories. There is a new model of story-telling which I call the statistical predictive story, and this type of story is threatening to marginalize our traditional, anecdotal story-telling tradition.

The first model is familiar to everyone. It is the default story-telling structure. It is rooted in the local, personal and based on low information or the original model the anecdotal story. The mission is to convey a personal story, which may be reports of old or new events that unfold over time. From five minutes ago to the distant past, stories are about others whose actions or behavior changed lives, they are sometimes celebrations of courage, and sometimes warnings about disloyalty or cowardice. Stories also confirm our biases, beliefs, and prejudices. You find these stories exchanged around a campfire, water cooler, over the dinner table, overheard in the elevator, stitched into books, film, TV, religion, politics, and family life. The audience is small in most cases. The story-teller is part of the community. We take for grant being an audience one moment and a story teller the next, and easily pass between the two states without much reflection. The story-telling process we are accustomed to is so pervasive that like the air we breathe we don’t see it, think about it, or go looking for it. The anecdote nurtures the psyche. They keep our emotional and intellectual engine fine-tuned and running, that allows us to locate our ‘self’ and explains the behavior and beliefs, desires, and needs of others we interact with.

The anecdotal story draws on personal experience, or the second-hand experience shared by others either as gossip, opinion, memories, beliefs, and feelings. In this form of story-telling, blends together from these elements. It is in the skill of a person touched by imagination that we think of as creativity. The magic of making a seamless composite of reality as the story unspools in front of the listener or reader. If you are labeled creative, it means you’ve succeeded in lifting the veil of doubt and convinced someone else that your story has merit, truth, or practical use when you find yourself in the wrong space at the wrong time. In reality, creative or not, we are all story-tellers and an audience for story-tellers.

The anecdotal story draws on personal experience, or the second-hand experience shared by others either as gossip, opinion, memories, beliefs, and feelings. In this form of story-telling, blends together from these elements. It is in the skill of a person touched by imagination that we think of as creativity. The magic of making a seamless composite of reality as the story unspools in front of the listener or reader. If you are labeled creative, it means you’ve succeeded in lifting the veil of doubt and convinced someone else that your story has merit, truth, or practical use when you find yourself in the wrong space at the wrong time. In reality, creative or not, we are all story-tellers and an audience for story-tellers.

Anecdotes merging real and imagined incidents, sights, slights, and motives are the kind of stories everyone tells. Some of these harden into myths, and myths transform into religion, and religion into identity. The anecdotal story-teller is what has created the structure of our culture, politics, and social life. Not to mention our relationship to economics. These are social constructs and they are built largely from anecdotes.

We’ve always known there were limitations on the accuracy and validity of the anecdote. What has been a sea change in story telling happened after WWII with the advances in computer science, physics, software development, and big data. The anecdote was highly personal and told eyeball to eyeball with the audience. The audiences were relatives, neighbors or family, expanding out to include the clan or tribe. Outsiders had their own audience and stories to tell. We resented an outsider telling a story about us—however we define ‘us’ didn’t matter, what mattered was leave our stories to our story-tellers. Our anecdotal stories were by their nature local, personal, and provided the social fabric out of which a community bond was forged.

While the personal anecdote created a communal social reality, solving the hard problem of how to achieve co-operation among a group of people with different needs, desires and goals. We used the personal anecdotes to explain how we are special in dealing with adversity and crisis, and we built ourselves and others from such stories. In other words, the story was a teaching tool to examine what was a good life in our group. In the last two-hundred years we began telling a second model of story-telling based on scientific inquiry and methods. In the last few decades, we used this model to discover unexpected patterns that emerge from large data sets. These aren’t our usual patterns processed from the raw material of lived experiences.

Banking, medicine, drugs, education, transportation and stock markets have invested heavily in this model of story-telling. What story-telling model would you wish your doctor to use if you should be confronted with a serious health issue? You’ve taken a battery of tests. The results are in. Your choice: The anecdotal story model or the statistical predictive story model? The first model is your doctor reads through your test results, your health background, ask you a number of questions about medication, etc. He scripts a personal story based on your specific results filtered through his own biases, and his prior experience of similar cases.

Banking, medicine, drugs, education, transportation and stock markets have invested heavily in this model of story-telling. What story-telling model would you wish your doctor to use if you should be confronted with a serious health issue? You’ve taken a battery of tests. The results are in. Your choice: The anecdotal story model or the statistical predictive story model? The first model is your doctor reads through your test results, your health background, ask you a number of questions about medication, etc. He scripts a personal story based on your specific results filtered through his own biases, and his prior experience of similar cases.

Or you could choose the second model asking your doctor to use the most advanced analytical tools at his disposal to upload your medical record and test results into a big data bank containing millions of people who have symptoms just like yours, similar age, gender, and genome. The networked system writes the story for your doctor. These are scary stories not intended to reassure a patient. Instead there would be a list of medical procedures or additional test with a chart of showing the probability of outcomes. Since the scriptwriter has high information, the best doctor, on his own, will be a degraded low-information medical provider. That’s part of the human cost of the second kind of story-telling. The statistical predictive story is not about you. It is about millions of people are like you, share your fear, needs, or medical condition. We haven’t quite made the transition between the story that is about us and one where you are largely irrelevant as an independent self. There is an uncanny valley, slightly creepy that comes from the sense of disappearing in a sea of numbers. At that moment, you as sit across from your doctor, you might be forgiven for asking who is making the decision? A human doctor or a machine programmed to analysis medical conditions. They represent two different focus points.

The anecdotal story traditionally has rested on the personal angle—what’s in the story-tellers frame of reference. We tell many personal, anecdotal stories every day. The story becomes impersonal once the analysis shift from an individual or small number of individuals, and expands to a large number of people. We continue to harvest the details of individuals. A system can predict an individual’s likely actions and choices. In the world of the statistical predictive story the value in a consumer society is in how the buyer’s attention is captured, held and manipulated. Retailers want to hear that story and pay large amounts to Google, Facebook, YouTube, and Amazon for access to this big data.

The anecdotal story traditionally has rested on the personal angle—what’s in the story-tellers frame of reference. We tell many personal, anecdotal stories every day. The story becomes impersonal once the analysis shift from an individual or small number of individuals, and expands to a large number of people. We continue to harvest the details of individuals. A system can predict an individual’s likely actions and choices. In the world of the statistical predictive story the value in a consumer society is in how the buyer’s attention is captured, held and manipulated. Retailers want to hear that story and pay large amounts to Google, Facebook, YouTube, and Amazon for access to this big data.

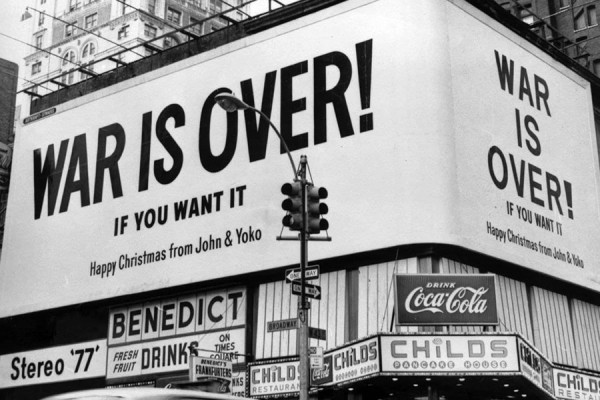

If you want to influence the outcome of an election, the Russian hackers need to find story points that score for a particular demographic of voter. You have to tell them a story that reinforces what they believe to be true. The Russian discovered big data allows you to define an audience in large numbers and to fashion stories as if you are around a campfire. One level of skill is to use computers and cloud data bases to gain insight into the preferences, fears, and anxieties of the audience.

In the world of high technology and science, an impersonal story is used like a scalpel to cut away the individual as the central actor of the story. In these stories, the personal is often a code word for the irrational. This hasn’t stopped articles, studies, books and movies about the personal stories of scientists like Einstein, Nash, Darwin, Hawking and Turing. We live in a world where most people know more that the personal life of a scientists than understand the equations and scholarly work that form the basis of their fame. This is the cadre of statistical, analytical and mathematical story-tellers whose stories drive this information acquiring system.

The kind of stories and the scale of persons allowed to be story-tellers expands and contracts over long periods of time. The reality is the zone available for the anecdotal story telling has been narrow and serving political and economic interest of an elite. Globalization and the Internet have combined to create a much wider and broader zone. Trump’s election showed millions of people wanted the old fashion anecdotal, personal, ad hoc stories that reinforced tradition suspicions and prejudice based on ethnicity, race, or religion. Like the wall Trump promised to build along the USA border with Mexico. That was a powerful story in itself—it promised to stop the flow of outsiders from crossing the border and bringing their own stories as psyche hand carry luggage.

People and their personal stories are mobile and with the Internet, outsiders have the means to evade the story censors. The old borders were built from anecdotal stories. The personal nature of such stories, in part, explains the high volume of hate and anger, with digital censorship to block the ridicule or questioning of leaders, examining their beliefs or criticizing their ideology. The flow of large seas of information continues and no one can risk cutting off that flow looking for offensive material while others are harvesting that information for economic, strategic or military gains. If that is the case, we should have evidence that the founding myths of most nations would be under siege. In reality, there has been a resurgence in the anecdotal story-telling tradition that lies at the heart of most modern populist movements.

People and their personal stories are mobile and with the Internet, outsiders have the means to evade the story censors. The old borders were built from anecdotal stories. The personal nature of such stories, in part, explains the high volume of hate and anger, with digital censorship to block the ridicule or questioning of leaders, examining their beliefs or criticizing their ideology. The flow of large seas of information continues and no one can risk cutting off that flow looking for offensive material while others are harvesting that information for economic, strategic or military gains. If that is the case, we should have evidence that the founding myths of most nations would be under siege. In reality, there has been a resurgence in the anecdotal story-telling tradition that lies at the heart of most modern populist movements.

If anecdotal story telling is not in a freefall while most of the most important sectors of life have transferred to the statistical predictive story telling the role to a small number of global cognitive workers and artificially intelligent machines and big data, are the two kinds of stories compatible? All the indications are they are not just incompatible, they are positively hostile to each other. The audiences are told all will be right once they can proudly tell their own personal stories, stick with common sense and anecdotes and forget the rest. Pride and ego intervene and probably always have. A fundamental problem with the old anecdotal story-telling tradition was often such stories reinforced the locals viewed that increasingly outsiders saw them as supporters of racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia. From the inside, they were blind to that message. There lies the rub. We have great difficulty retaining this story-telling tradition as a construction of individual and collective identity without being condemned as a bigot, racists, or sexist. The kind of stories we tell and listen to locate the threshold that triggers cognitive dissonance. And a fight breaks out. Few people reflect on what it means to accept that your beliefs, values, and desires constructed from innumerable anecdotal stories from early childhood.

We have a generation who are getting their stories from the global library, and the international group of story-tellers are transmitting stories that may conflict or contradict what they learned at home or school. As story-tellers compete for the attention of an expanded global audience, the stories essential to sustain local cultures are threatened. Stories that inspire are no longer exclusively based on local elites, celebrities or events. In the case of Xi Jinping, the Chinese censors have banned Winne the Pooh as the image of the beloved children’s character has been used to ridicule him. Stories can wound. Our attention to stories remains a central part of our self-perception and how we perceive others. That means stories have social, political and economic consequences that can create shock waves far beyond what the story-teller intended.

The statistical story has disrupted and threatens to displace the anecdote. Though we have witnessed that millions if not billions of people are unwilling to shift from the anecdote to the statistical even if it is convincingly argued their view of themselves and the world will be more accurate, reliable, and objective. The point is we have a great deal of difficulty to shedding our addiction to the subjective story. It may be inaccurate, unreliable and personal, but it seems more real, we are more moved, connected, or influenced because the anecdote is the way our emotional system communicates with us and the community.

The statistical story is generated by processing large amounts of data, interpreting the data, creating a theory (a story) to explain how the interpretation of the data is actionable. Information is controlled, updated, expanded, shared, stored, sold and traded to sell policies, personalities, beliefs, products and services. It is impersonal, difficult to understand, and in constant flux. The statistical story keeps changing and shifting. Science approach to story-telling has awakened people to the dangers of the anecdote. Many have reacted by supporting reactionary leaders who promise a way back to when anecdotal stories had respect and those who told such stories were pillars of the community.

The statistical story is generated by processing large amounts of data, interpreting the data, creating a theory (a story) to explain how the interpretation of the data is actionable. Information is controlled, updated, expanded, shared, stored, sold and traded to sell policies, personalities, beliefs, products and services. It is impersonal, difficult to understand, and in constant flux. The statistical story keeps changing and shifting. Science approach to story-telling has awakened people to the dangers of the anecdote. Many have reacted by supporting reactionary leaders who promise a way back to when anecdotal stories had respect and those who told such stories were pillars of the community.

The statistical story-telling method has weakened the old institutional story-telling institutions from churches, to political institutions, to schools and universities, and the core of life: the family unit. We are entering a world where human being will be replaced as the primary story-telling species. One reason is the statistical story hold the promise of making our decision-making and problem solving far more efficient. We will make fewer mistakes relying on such stories. Like the horse which had been central to our agriculture and transportation system, it will take fifty years before the old story-tellers are put out to pasture. The anecdote will be dismissed as primitive and crude means of conveying information and forming group solitary but did little to decrease ignorance of reality. We are at an inflection point and people are willing to defend their stories with their lives. We’ve never had a period where the global population has been under intense pressure to shift their identity and reality from myths, legends, and fables and embrace a radically different kind of story-telling with a new rank of story-tellers. An indication of the seriousness is the reality Islam has declared jihad on the modern story-tellers.

Future generations will produce a different mind map of children, who are raised on statistically generated stories that predict the future in terms of probabilistic outcomes. If that comes about, it is likely such children will be dismissive of the relevance of anecdotal story-tellers from the past. Religion as we know it won’t survive the statistical predictive story culture. No one today reads Aristotle today to study his insights into the laws of physics. He was wrong about everything we now know about physics. We read him for his teachings about what makes us human. The anecdotal story conveys that message well. A meta-physics question is what space will remain for the traditional, low-information, flawed story that feed an emotional need? Can the two forms of story-telling co-exist? The answer will determine how we think and feel about ourselves and society.

Christopher G. Moore

Christopher G. Moore, a Canadian novelist and essayist, living in Bangkok, is CrimeMag South East Asia correspondent and the author of the award-winning Vincent Calvino series and a number of literary novels and non-fiction books. His books have been translated into 13 languages. The Christopher G. Moore Foundation is awarding a literary prize for a work of non-fiction, which advances understanding of human rights and freedom of Expression.

A (German) review of his novel „Springer“ (Jumpers) here.

„Bloody Questions“ from Marcus Muentefering here.

His essays with CrimeMag here.

His website here.