Jock Serong – (e)

Christoph Thoke –

David Whish-Wilson – (e)

Benjamin Whitmer – (e)

Robert Wilson – (e)

Matthias Wittekindt –

Jock Serong: Lost and Found

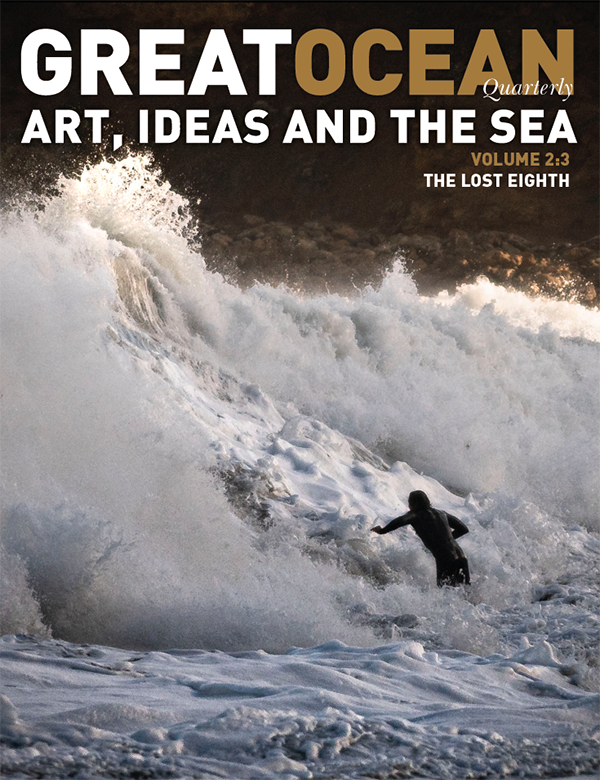

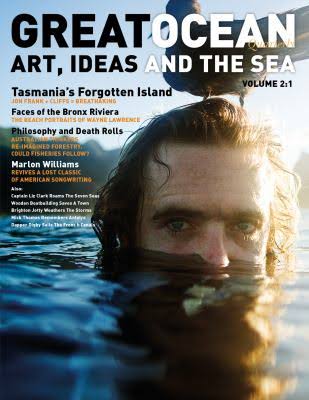

Back in 2013, I somehow became involved in the launch of a magazine about the sea, a beautiful big heavy art journal called Great Ocean Quarterly. It was just me and my friends Mick and Mark against the world; and it turns out we were good at making words and pictures, but sorely lacking in publishing experience. The more copies we sold, the more money we lost. And that, I am reliably told, is not an ideal business model. After seven issues and with an eighth one waiting to go, we had to close the doors in 2015. It was a bitter lesson.

But this year, for reasons which will become clear below, we decided to re-launch that ‘lost eighth’ issue, and the project was an unexpected joy. The editorial that I wrote for the Lost Eighth just a few weeks ago probably still stands as my personal reflection on everyone’s hellish year.

***

Five years.

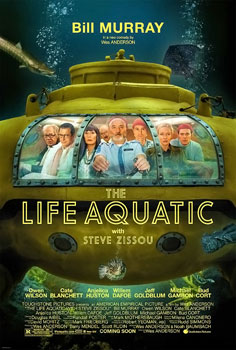

When I see the words I hear the Bowie song, sung in Portuguese over acoustic guitar by Seu Jorge on the deck of the Belafonte in Wes Anderson’s greatest film (I will brook no argument), The Life Aquatic.

Five years is how long it’s been since our last issue. There’s been much to celebrate, and much to mourn. Five years of steady increase in sea temperatures, in sea levels and ocean acidity. Five years of species loss, coral depletion and migratory birds that never returned.

Closer to home and more specifically, our founder Mick Sowry lost his beautiful wife Sue. In a way, it’s Sue’s fault that you’re reading this. Her funeral was a celebration of her lust for life and her raucous indifference to hardship. We gathered at her wake, Mick bereft but gracious, and we talked about making something good out of grief. There was some beer. Marky got enthused. And here we are.

We knew this issue was still alive somewhere in the chaos of Mick’s office, banging at the digital walls of a hard drive and demanding release. We knew some of the articles had been published elsewhere in the interim and would need to be replaced. We’d need to find some new ones. We’d need to honour the promise of the old ones. There would be work to do.

And then, of course, the world flipped on its head. Among much graver concerns, a great many of us were separated from the coast by circumstance. The lockdowns and restrictions have impacted the production of this Lost Eighth issue, but they’ve also fired the turbines: suddenly there was a pressing reason to raise the necessary money and make the magazine. People needed a lift.

That’s not unique to GOQ or its readers, of course. One of the redeeming features of this dark tide is a return to making and thinking, slowing down and re-evaluating what matters. Many people will never live, or work, the same way again. Entire cities will re-configure themselves. The role of the coast in our communities, and of communities in our coasts, will fundamentally alter.

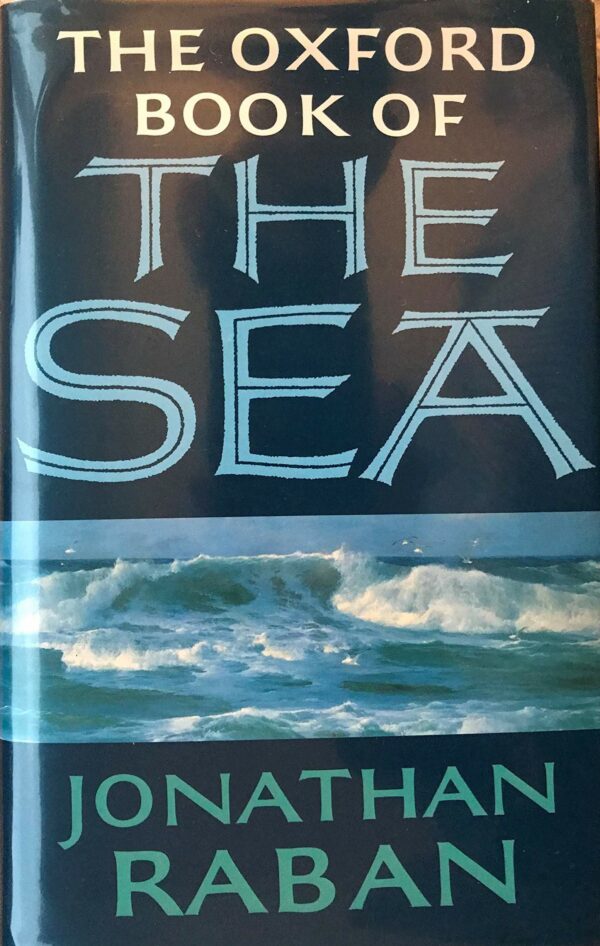

I went looking for something or other in Raban’s Oxford Book of the Sea, and I was struck by how much oceanic writing is driven by notions of the sea’s pitilessness, its indifference to human wants. But there’s comfort to be had in that idea as well. In a pandemic, in an age of rampant intolerance and separation, the fanatical primacy of the self, the ocean doesn’t care. It is there, it is there.

The tide leaves and returns, the swell rises and falls in response to faraway storms; the wind explores the compass. In the times I’ve gone there near dark, clad in hooded rubber so that I exist only as two squished cheeks stubbled like a porcupine fish, I’ve found a migration of like-minded others. Mostly teenagers, but all sorts of people. Surfing, yes, but swimming, paddling, throwing themselves heedlessly at the waves that don’t care, exactly because the waves don’t care. Because here is something beyond anxiety, beyond argument. Here is only physics, and the coming dark. All of the psychic moving parts are within us.

Losses – the loss of money or health or freedoms – are the distillers of the stuff that really matters. Mick lost Sue, and among the gifts she left was a reminder to make something good out of sadness.

Here is that something. It’s dedicated to Sue.

Jock Serong’s piece about the Australian Wildfires at CulturMag here: „Blackened and Bewildered.“ His new novel The Burning Island was published by Text, Melbourne, in September 2020. He is the author of Quota, winner of the 2015 Ned Kelly Award for Best First Fiction – translated into German as Fischzug, published by Polar Verlag; The Rules of Backyard Cricket, shortlisted for the 2017 Victorian Premier’s Award for Fiction, finalist of the 2017 MWA Edgar Awards for Best Paperback Original, and finalist of the 2017 INDIES Adult Mystery Book of the Year; On the Java Ridge, shortlisted for the 2018 Indie Awards, and recently, Preservation. His books at Text Publishing, Melbourne, here.

Christoph Thoke: Mein kleines Jahr

Anfang des Jahres tat ich es etwas ganz und gar kleines.

Etwas zur persönlichen Entspannung.

Und begann einen Zeitvertreib.

Ich nahm mir vor, jeden Tag ein eigenes Bild zu posten.

Mit einer Überschrift.

Die kommentiert.

Zum Nachdenken anregt.

Oder auch mal nur unterhalten darf.

Ganz nach Laune eben.

Ein privater Spass.

Auch wenn das Private öffentlich werden sollte. Bei Twitter.

Aber war Twitter nicht eh etwas für Journalisten und wahnsinnige Politiker?

Egal.

Es musste nur noch ein Name her.

Ein hashtag.

Etwas zum Einstimmen.

Und am 4. Jänner startete dann die Chose.

Unter #Mainzflaniert.

Mit einem Bild vom Dom.

Wie naheliegend auch. Lebe ich doch in Mainz,

Wenn mich das Filmproduzieren nicht in die Ferne treibt.

Ferne. Ja Ferne.

Was für ein waghalsiger Begriff.

Üblicherweise reise ich ja viel.

Und im Februar wollte ich nach Berlin.

Zur Premiere. THERE IS NO EVIL ist mein letztes Projekt.

An dem ich beratend beteiligt war.

Ein Iranischer Film.

Über die Greuel des Regimes.

Und ich wollte die anderen Mitglieder des Teams treffen.

Doch da war schon etwas.

Im Iran.

Nicht Grosses.

Nur ein paar Fälle.

Von dieser neuen Sache.

Und ich stellte mir vor, wie da so sein würde, mein Teamtreffen.

Man umarmt sich, herzt sich.

Jetzt wo der Film gegen alle Widerstände geglückt ist.

Freude. Pure Freude.

Und keiner hatte den Golden Bären auf dem Plan.

Bin ich also zu hause geblieben.

Zwei Wochen vor dem ersten Einschluss.

Und habe mir die Zeit vertrieben. Und dann die Enttäuschung nicht dabeigewesen zu sein.

Mit lustigen kleinen Posts.

dav

cof_soft

cof_soft

ptr

ptr

oznor

cof_soft

cof

sdr_soft

Und meinen Photos des öffentlichen Raum.

Von Türklinken, absurden Verkehrszeichen. Stilleben.

Wie eine Reise durch die Stadt.

Und ihren Geheimnissen mitunter.

Nur während einer kurzen Reise im Sommer ruhte meine tägliche Produktion.

Denn mein Zeitvertreib sollte befristet sein.

Auf ein Jahr.

Christoph Thoke ist Weltreisender in Sachen internationale Kino-Coproduktionen.

Hessischer Filmpreisträger.Jetzt wo der 2. Lockdown über Deutschland gekommen ist, verfasst er weiterhin seine Posts unter: @mogadorfilm

Der Film THERE IS NO EVIL hat nach einer mehrmonatigen Pause, in der in der internationalen Filmbranche völliger Stillstand herrschte, weitere Preise und ein Vielzahl von internationalen Festivalenladungen erhalten. Der Deutsche Kinostart wurde allerdings auf das Frühjahr 2021 verschoben. Christoph Thoke bei uns hier.

Christopher Werth: Krieg, Revolution und Spiele.

Krieg: 2020 war auch das Jahr der Kriege. Die meisten davon registrieren wir in der Regel nur, ohne eine emotionale Verbindung zu den Opfern zu entwickeln. Anders war es diesmal bei mir mit dem Bergkarabach-Konflikt. Irgendwann tauchte dieser Song in meiner Playlist auf. Eine kleine Sensation: seit Ewigkeiten was Neues von der Alternative-Metal-Band System of a Down. Ungewöhnlich eingängig und direkt für ihre Verhältnisse. Der Song setze sich fest, lief irgendwann in Dauerschleife, und ich spielte das Riff im Proberaum nach. Dann erst achtete ich auf den Text und sah das Video. Es geht um knallharte Politik, einen geopolitischen Konflikt. Aserbaidschan vertreibt Armenier aus Bergkarabach. Das traf mich dann um so härter und brachte mich dazu, intensiv über den sehr alten und sehr komplexen Konflikt zu recherchieren. Ein Beleg für die Erkenntnis der aktuellen Hirnforschung, dass wir erst dann bereit sind, neue Dinge zu denken und zu lernen, wenn wir emotional berührt worden sind.

- Protect the Land von System of a Down

Revolution: 2020 war auch das Jahr des Mauerfall-Jubiläums: Es jährte sich zum 30. Mal. Der antifaschistische Schutzwall ist jetzt länger weg, als er je die beiden deutschen Staaten voneinander getrennt hat. Die Nachwirkungen sind heute mehr denn je zu spüren. Viele Forderungen der friedlichen 1989er Revolution sind nach wie vor extrem relevant: Gleichberechtigung, Nachhaltigkeit und ein gerechteres Wirtschaftssystem. Im Buch Empowerment Ost erzählt Thomas Oberender (hier im Interview mit Politik & Kultur) seine ganz persönliche Geschichte von dieser in der Geschichte einzigartigen Revolution – und von dem, was leider noch nicht daraus gemacht wurde. Hochspannend eröffnete der Text mir als Wessi einen neuen Blick auf die Seelenlage unseres Landes.

Einen anderen Ansatz verfolgte nach der Vereinigung die dritte Generation der RAF. Mit der Exekution von Treuhand-Chef Detlev Karsten Rohwedder wollten sie ein Statement gegen die Massenentlassungen setzen und einen faireren Umgang mit der „Konkursmasse“ der Ex-DDR fordern. In vier Teilen beschäftigt sich die Dokumentation Rohwedder im True Crime Stil mit den verschiedenen Aspekten dieses bis heute nicht aufgeklärten Verbrechens.

- Empowerment Ost Wie wir zusammen wachsen, Tropen Verlag, Stuttgart 2020

- Rohwedder, Netflix 2020

Spiele: 2020 war auch das Jahr der geschlossenen Theater. Trotzdem konnte ich die zurzeit vielleicht spannendste Theatermacherin kennen lernen und mehrfach ihre Aufführung von Shakespeares Sturm erleben. Es geht um Samantha Gorman. Sie stellte sich die Frage: Wie können Schauspieler:innen aus ihren Wohnzimmern heraus Geld verdienen und in Kontakt zum Publikum treten? Sie entwickelte ein VR-Spiel, bei dem keine Vorstellung der anderen gleicht und bei dem Menschen aus der ganzen Welt gemeinsam mal kurz die Pandemie vergessen dürfen, um einen unvergesslichen Trip inspiriert von Shakespeare zu erleben.

- VR Game: The Under presents Tempest

Hier geht es zu unserer Rezension dieses Spiels im CulturMag. Christopher Werth, der bei uns die Kolumne „Playing Video Games“ schreibt und auch sonst exzellenten Geschmack hat, mit seinen Texten hier.

David Whish-Wilson

As a night-owl whose eyes burn with too much daytime writing and reading, in the wee hours I turn to television series to keep me entertained and to see me over to the other side. Many people think of The Sopranos when they think of the first 60 minute episodic television series with long and patient character and narrative arcs, but to me it was always HBO’s Oz that introduced me to the pleasures of the form. Like many this year, I suspect, there has been a return to the comforts of the familiar, and while I’ve enjoyed revisiting Gomorrah, Black Mirror and (for the fifth time) Deadwood, re-watching Oz in its 56 episode entirety has been a significant pleasure. Set in the fictional Oswald State Correctional Facility, in a prison within a prison (Emerald City), the goldfish bowl scenario captures the psychological tension and emotional subtext of inmates and staff members living under terrible pressures, reading one another while often blind to themselves. Shakespearean in its webs of deception and shifting allegiances, theatrical in its delivery and insights, alternatively blunt, subtle and punctuated with terrible violence, re-watching Oz during the build-up to the US election cast the tribalism, libidinous megalomania and ruthlessness played out there in the clearest light.

My favourite crime novels this year were similarly fierce. Adam Morris’ Bird (Puncher & Wattman, 2020) is a circular narrative that swirls around the character of Carson, a charismatic young Aboriginal man in and out of jail. Told from the POV of prison guards, psychologists, teachers, friends and thugs, the picture builds up a young man who in a different circumstance might have been anything at all. Darkly comic and sadly absurd in its examination of the damage that crime, racism and the effects of incarnation have on those who turn the key, as well as those locked up, the language is pitch perfect in its rendition of a young man whose horizons are limited as much out of jail and within.

One of the best crime novels I read this year hasn’t been published yet. Ruth McIver’s I Shot the Devil (Hachette Australia, 2021), whose publication was delayed due to covid, is a whip-smart look at the murder of a young man in a Long Island suburban woods, set against the background of the satanic panic that emerges when the main suspect’s alleged predilections are made public. Erin Sloane, now a hard-bitten journo, is tasked to return to her hometown nearly twenty years after the murder took place. Erin was there on the night of the murder, and her friends were blamed. Erin’s investigations take her deep into the dark heart of her family history, and those of her then teenage friends, each of them damaged and complicit, their parents also, building up a telling picture of dysfunction that is far more chilling than the ludicrous tropes of satanic panic propagated by the media at the time. McIver’s writing is sharp, precise, insightful and fierce, and I Shot the Devil is one to look out for next year.

2020 has been a good year, too, for follow-up narratives by some of my favourite Australian crime writers. I’ve greatly enjoyed Jock Serong’s The Burning Island, which takes place in the early 19C, several years after the dramatic reckoning that formed the conclusion of Serong’s excellent Preservation (one of my all-time favourite Australian historical novels). I’ve also enjoyed Alan Carter’s Doom Creek (Fremantle Press, 2020), his second novel in the Nick Chester, New Zealand set series, following on from Marlborough Man, which won the Ngaio Marsh award a couple of years back. Other favourite reads include Dave Warner’s new novel, Over My Dead Body (Fremantle Press), JP Pomare’s In the Clearing, Megan Goldin’s The Night Swim, and Patrick Holland’s (who it seems to me is one of Australia’s most underrated writers) The Darkest Little Room (Transit Lounge, 2012) – a dark and clever Vietnam-set mystery.

David Whish-Wilson is the author of True West (CrimeMag review here), of The Cove (CrimeMag review here) and some other fine novels. His Frank Swann novels are translated in Germany, published at Suhrkamp. Book 4, Shore Leave, was just published in Australia. Dave’s presence at CulturMag. His website.

Benjamin Whitmer

Its been a rough year, not gonna lie. I can’t even remember most of what I read, and some albums came and went, but I don’t remember a lot of it. I’m sure I could if I tried, but who cares?

I did watch a lot of television though. My favorite show is called Alone, and it’s about a bunch of folks who get dropped off in the wilderness with nothing but a knife and a tarp, and whoever stays there the longest gets $500,000. The best part is how they talk big in the first episode about all they’re gonna prove to themselves out there, but nope, all any of them proves is that they ain’t shit. They don’t learn anything neither unless they’re idiots. There’s nothing to learn. It’s the anti-manifestation show. It’s nothing but who can starve the longest.

And I’m for it. I like to sit on my bed in my warm room and eat ice cream and watch their faces hang off. Its been a pandemic lifesaver. I’ll watch any show that’s nothing but dumb fuckers starving themselves for money. I don’t even need the gimmick. They could film it in a phone booth and I’d watch it. Anyways, fuck 2020. I hope to forget everything from this year.

Benjamin Whitmer is one of Wolgang Franßen’s favorite authors. He published Im Westen nichts (Pike) and Nach mir die Nacht (Cry Father) in 2016 and 2017 at Polar. Ute Cohen (also in this Year’s-end-issue) wrote a review titled „Wildromantische, vogelfreie Scheisse“, and CrimeMag published the opening pages of the aptly named Im Westen nichts. In the West – Nothing. Ben’s novel Flucht (Old Lonesome) about a jailbreak at New Year’s Eve 1968 in Colorado, translated by Alf Mayer, was published in spring 2020 by Wolfgang Franßen – during Corona times.

Robert Wilson

It’s been quite a year, one that we’ll never forget. It’s difficult to believe in January, as we puzzled over a strange animal to human leap in a Wuhan wet market, that we would find ourselves, within weeks, in the grip of an unseen enemy that would strike at the elderly, the vulnerable and even the young and healthy.

It seems ridiculous to write about books, movies, plays and music in a year where there was a huge hiatus in publications, a closure of production studios, a bar across theatre doors and a moratorium on musical performances. So this year I thought I’d put together a selection of weird and wonderful moments.

January. Having finished Vassily Grossman’s Life and Fate at the end of 2019 I decided that such a huge and powerful work, which the writer never saw published himself, should be shown the respect of being re-read. It’s a good book for those feeling bleak about our polarized world. This is the battle between the great ‘isms’ of Communism and Fascism, but Grossman concentrates this colossal confrontation on the turning point of WW2: the heroic Russian defense of Stalingrad. The genius of his story, however, is that where these counterforces meet he manages to discover a humane solution, which would become my single most important belief of the year.

Yes, as well as this terrible Good with a capital ‘G’, there is everyday human kindness… The private kindness of one individual towards another; a petty thoughtless kindness; an unwitnessed kindness. Something we could call senseless kindness. A kindness outside any system of social or religious good.

Human history is not the battle of good struggling to overcome evil. It is the battle fought by a great evil struggling to crush a small kernel of human kindness. But if what is human in human beings has not been destroyed even now, then evil will never conquer.

March. I was walking down this avenue of trees in Shotover Country Park on the outskirts of Oxford.

Covid 19 was already upon us. The UK had seen its first death and hospitals in Italy and Spain were under siege conditions. Nobody quite knew how serious the pandemic would become in terms of loss, but what came over me on that sunny afternoon walking the dog was a sudden feeling of great sadness that the world as we knew it was going to change for ever.

March 23rd – June 1st. Lockdown in the UK. Waking up to a silent world. No cars, no people, no shops, no pubs. Life suspended on the outside while strange combinations of people try living together on the inside. The loneliness of the elderly, alone at home or unvisited in carehomes, is acute. Masked people queue for food each within their two metre forcefield. We crave faces and practice communication with our eyes. The real world is too strange, stranger than the wildest fiction, making it impossible to invent or consume the printed word. Miraculously the sun shines every day and the air gradually clears. The quiet brings wildlife to urban gardens. Birds crowd the trees and lawns. The bluebells in the woods have an aching beauty in this the most wonderful Spring for years. Families who have never walked together can now be seen beneath the budding trees looking up at the trembling new leaf so bright and green. Is this the start of something different? Is this what they meant by ‘the new normal’, that we would be people again, rather than consumers?

June. Finally I am able to reach for some fiction. I read Steinbeck’s East of Eden for the first time. How has this book eluded me? I am entranced, in our polarized world, by a writer who is determined to make us see that we must live with both Good and Evil inside us, but that we also have Timshel, ‘Thou mayest’, a choice. Had lockdown made me more emotional? I cried twice reading this book. The second time was when the lovely Abra expresses her wish to become the daughter of Trask’s marvelous, philosophical Chinese manservant, Lee. The first time must have had something to do with the unavailability of the truth in our 2020 world. Samuel Hamilton, the Irish farmer of the poorest land in the Salinas valley, is, in the estimation of his children getting too old for this kind of life. They agree to relieve their parents of the burden of work by inviting them to stay with each of their families in turn, but…they won’t reveal this strategy for fear it will cause hurt. Tom, the son who is working with his father, does not like this. He would prefer to tell the truth. While Tom and Sam are working in the barn one of the sisters calls to make the first invitation. Afterwards Sam asks Tom if he’d mind if he and his mother ‘took a little trip’. Tom, a poor actor, lies on behalf of his siblings, but the truth glares out and Sam relieves him by revealing that he knows what’s going on.

“I wasn’t in favour of it,” said Tom.

“It doesn’t sound like you,” his father said. “You’d be for scattering the truth out in the sun for me to see. Don’t tell the others I know.” He turned away and then came back and put his hand on Tom’s shoulders. “Thank you for wanting to honor me with the truth, my son. It’s not clever but it’s more permanent.”

Thank you for wanting to honor me with the truth. That was the line that broke me apart.

July. We left UK and headed down through France and Spain to my writing hideaway in Portugal. It was sobering to see the Spanish all masked up in the streets and shops, but at least they were out and about, just a little subdued. Somehow we’d been hoping that the isolation of the house in the rural Alentejo would mitigate the effects of the pandemic. It was not to be. The phone didn’t work and the company wouldn’t repair the line, so we were even more cut off. Some of our friends had suffered from Covid and were being very careful about seeing people, others, after long and draconian lockdowns, were alarmed at being out in the world. The atmosphere was tense, the future uncertain. Added to that the heat was brutal and lasted into October. But I worked. The WW2 novel was rewritten…again. The new novel was researched and started.

August. My book of the year. Apeirogon by Colum McCann. What is most remarkable about the book is its structure. The friendship of Bassam and Rami, a Palestinian and an Israeli, who have both lost their daughters to violence, is at the heart of it. Their unbearable stories are told right in the centre after the 500 sections that lead up to and then the 500 sections that lead away from 1001, alluding to One Thousand and One Nights ‘a ruse for life in the face of death’.

These sections can be anything from a line to several pages long. They consist of an extraordinary range of thoughts, ideas, observations, lines of poetry, facts and descriptions. They are also infused with the stories of Rami and Bassam and many others who find themselves in the chaos of this long conflict.

It is a book about the search for peace. As the 13th c Persian poet Rumi said: ‘Beyond right and wrong there is a field, I’ll meet you there.’

Bassam understands the horror of the Holocaust. Rami understands the humiliation of the Occupation.

Both know that peace will have to come however much the powers that be struggle against it.

‘It will happen at the moment when the price of not having peace exceeds the price of having peace.’

November. We return to the UK and into a compulsory two week quarantine during which we learn that Oxford City has entered Tier 2 Restrictions. A few days later we are told that the UK will go into Lockdown 2.0. I read The Unconsoled by Kazuo Ishiguro. It seems an appropriate book for such a strange year as, for its 535 pages, it relentlessly follows the bizarre logic of dreams as its characters aimlessly pursue and attach misplaced importance to their human goals, while wasting their lives by failing to engage and missing every opportunity for real human intimacy.

Could 2020 have ended in any other way than Joe Biden winning the US election while Donald Trump refuses to accept the result?

The French philosopher Pascal suggests that ‘all of humanity’s problems stem from our inability to sit, alone, in one room.’

Only connect.

Well-travelled Robert Wilson is the author of the Bruce Medway-, Charles Boxer- and Javier Falcon-novels. In 2003 his novel Tod in Lissabon (A Small Death in Lisbon) won the „Deutscher Krimipreis“. He has finished a manuscript for a WW II-thriller, set among the exiles in France and Portugal. His appearance at CrimeMag here, his essay about Vassily Grossman: Book of the Hour.

Matthias Wittekindt: Gespräche am Topf

Zeit für die großen Feuer. Zeit für die durchgeglühten armdicken Stämme der Ulme, die vor zwei Jahren fiel. Zeit vor allem natürlich für die Zwiebeln, das Fleisch, den Paprika und den alten, schwarzen Topf der böhmischen Oma. Denn nun wird es endlich kalt, geht in Tippelschritten auf Weihnachten zu. Ein paar Tage später, so ist es seit langem die Regel, kommt Silvester. Wobei Silvester in diesem Jahr gleichzeitig kommt und ausfällt.

Ich bin schon gespannt auf den Jahresrückblick im Fernsehen. Auch wenn ich mir den nie ansehe, so wird er dieses Jahr doch sicher recht prall ausfallen. Ich kann mir allerdings gar nicht vorstellen, dass irgendwelche sportlichen Glanzleistungen, der Sommerhit des Jahres, das drolligste Supertalent, die abgedrehteste Bademode für Männer oder ähnliches Erwähnung finden. Schlimmer noch! Dieser Markstein des Jahreswechsels, die Freude, das neue Jahr zu begrüßen, die melancholische Stimmung anlässlich der Verabschiedung des alten, die Einteilung des Lebens in Abschnitte, macht fast keinen Sinn.

Oder?

Was für ein Jahr! Eine Flut an Informationen. Ein endloser Strom an Gedanken und Gegengedanken, Glaubensbekenntnissen und Gegenglaubensbekenntnissen, geschrieben, gefilmt, gesprochen, gebrüllt. Vielleicht bin ich geschwächter als ich meine und von der latenten Bedrohung durch die grassierende Krankheit nur etwas gereizt und übersensibel. Aber ich habe im Moment das Gefühl, mich wie ein mäßig verankerter Felsbrocken in einer Art reißenden Strom zu befinden, der immer weiter reißt und reiß und reißt, komme, was wolle, der weiter an den Ufern nagt und kleinere Ortschaften, Schulklassen, einsame Wanderer, ja sogar Hunde, Katzen und Pelztiere verschlingt, ohne sich dabei um einen Markstein wie Silvester oder die Begrüßung des Neuen auch nur im Geringsten zu kümmern. Ich jedenfalls kann mir nur schwer vorstellen, innezuhalten. Obwohl ja Felsbrocken genau das in der Regel tun.

Worauf also läuft es hinaus am Silvesterabend?

Essen und trinken mit Antje und meiner Schwiegermutter. Das immerhin wird sicher schön. Unsere Töchter, mein Schwiegersohn, meine Enkelkinder, die werden natürlich nicht alle dabei sein.

Und doch.

Eigentlich war es, wenn ich mich einen Moment lang nur auf mich selbst besinne, ein gutes Jahr. Ich hatte zum Beispiel nie das Gefühl etwas zu verpassen, und …

Das Gute an katastrophalen Zuständen ist ja stets der Moment der Inversion. Jeder Autor, jeder Verleger, Lektor und Kritiker kennt diese Momente. Wie sagt man so schön: ‚In der Not wachsen dem Teufel neue Flügel.‘ Mit Felsbrocken, man mag es kaum glauben, verhält es sich ähnlich. Ein wundersames Kraftmoment macht sich breit.

Das alles dachte ich gestern. So gegen Mittag beim Schälen der Zwiebeln. Und beim Schreiben danach. Noch bevor ich mich ums Fleisch kümmerte.

Doch dann … Oh je!

Wie immer, wenn ich etwas schreibe, überprüfe ich vor der Versendung, ob man überhaupt versteht, was gemeint ist. Gleich gestern Abend, am Lagerfeuer, ergab sich die Gelegenheit. Ich las also vor. Die anderen – orangerote Gesichter, den Blick starr ins Feuer beziehungsweise auf den Topf mit dem Gulasch gerichtet – hörten zu und dann … War ich fertig. Und dann … hob es an.

„Nein, Matthias“, sagte Alice entschlossen, „ich sehe das genau anders herum. Da ist nichts Reißendes, es ist still geworden. Jedenfalls für mich.“

„Still geworden nennst du das?“, sagte daraufhin Antje. „Es herrscht einfach nur das totale Chaos? Und es geht gerade sehr viel kaputt, im Kulturbereich.“

Nun meldete sich Jens zu Wort. „Ich weiß nicht, aber wir hatten dieses Jahr so viele Aufträge, so viel Förderung …“

Jeder hatte seine Empfindung, seine Meinung zu diesem außergewöhnlichen Jahr. Es ließ sich partout keine Übereinstimmung finden. Erst später dann wieder. Beim Gulasch. Aber möglicherweise spielte da auch der Glühwein mit rein.

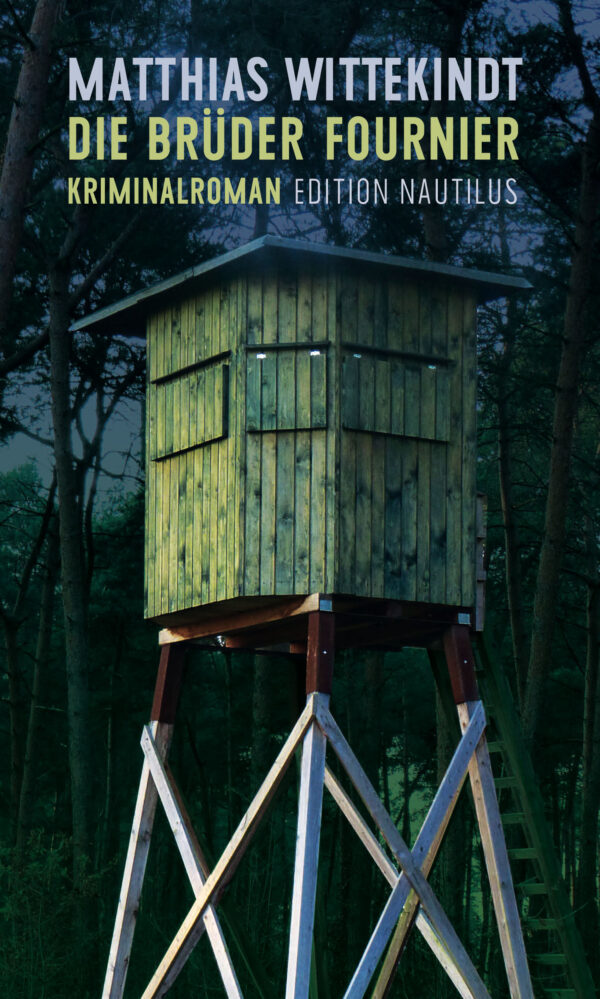

Die Brüder Fournier heißt das Buch von Matthias Wittekindt, das im Frühjahr 2020 während Corona bei der Edition Nautilus herausgekommen ist. Dort sind fünf weitere Kriminalromane von ihm erschienen.