Die Würde behalten – in der Gosse

Die Würde behalten – in der Gosse

– Etliche Zeit bevor der trunksüchtige Detektiv zum Klischee wurde und Alkoholismus zu einem jener zahlreichen Gebrechen, mit deren mindestens einem ein fiktionaler Held heutzutage zwingend aufwarten muss, erfand einer der Großmeister der Kriminalliteratur einen Helden, der in der Gosse lebte. Allerdings hielt er ihn nur für acht Kurzgeschichten und einen einzigen Roman am Leben; es brauchte dann an die 20 Jahre, bis Lawrence Block, ebenfalls ein New Yorker mit Leib und Seele, in einer Art Staffelübergabe diesen Faden aufnahm und mit Matthew Scudder (der hier noch einen Auftritt haben wird) nun seit mehr als 35 Jahren und 17 Romanen einen (mittlerweile) Ex-Alkoholiker ermitteln lässt.

Es war Ed McBain (1926–2005), der 1953 einen ehemaligen Privatdetektiv erdachte, der sich in der New Yorker Bowery als „skid row bum“ durchschnorrt und durchsäuft und lange genug nüchtern zu bleiben vermag, um ein paar Leuten zu helfen. 1945 war hier Ray Milland als Hauptdarsteller von Billy Wilders „The Lost Weekend“ durch die Straßen getaumelt (siehe Teil III). McBains tougher Alkoholiker Cordell (später umbenannt in Curt Cannon) erschien erstmals im Januar 1953 in der Startausgabe des Magazins „Manhunt“, der Titel der Geschichte – hier ein Gruß nach Hollywood und Bruce Willis – war „Die Hard“.

Die Ankündigung las sich so: „Cordell was washed up. His license was gone, his wife was gone, and his self-respect was gone. All he had was a glass of whiskey and a dead man on the barroom floor.“ Der Anfang lautete: „The bar was the kind of dimly-lit outhouse you find in any rundown neighborhood, except it was a little more ragged around the edges. The mirror behind the bar was cracked, and it lifted one half of my face higher than the other. A little to the right of the bar was a door with a sign that cutely said, ‚Little Boys‘. The odor steeping through the woodwork wasn’t half as cute.“

Ed McBains „noir chops“

Ed McBains „noir chops“

Acht Geschichten mit diesem Helden erschienen 1953 und 1954, ehe der gleiche Autor unter dem Pseudonym Evan Hunter 1954 mit dem Roman „The Blackboard Jungle“ („Die Saat der Gewalt“) großes Aufsehen erregte. Es war ein Buch, das die gesellschaftliche Paranoia definieren half, die das Leben nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg zunehmend überschattete (siehe Teil III, Teil IV und Teil V). Es war ein realitätstüchtiger Blick auf die sich zuspitzenden Konflikte der Stadtgesellschaft, auf Schule, Jugend und Erziehung, und es stellte viele Grundannahmen in Frage, derer man sich im konservativen Amerika sicher geglaubt hatte, allen sichtbaren Veränderungen zum Trotze.

Der in Brooklyn geborene Evan Hunter wusste als ehemaliger Lehrer wovon er schrieb. Jugendliche Straftäter und Delinquenten, angestachelt von etwas, das sich Rock’n’Roll nannte, wurden zum Schrecken der Dekade. Sex und Drogen tauchten aus der Versenkung auf, Schuld daran hatten die rebellischen Teenager – so die Reaktion auf die Realitäten des Romans. Schon im Jahr darauf kam die Verfilmung von Richard Brooks in die Kinos, mit Glen Ford als dem idealistischen Lehrer. Bei ihm Zuhause, so die Fama, hörte Brooks zum ersten Mal den Song, mit dem er dann den Film beginnen und enden ließ: „Rock Around the Clock“ von Bill Haley & His Comets. Der Film machte den Song zu einer der meistverkauften Singles aller Zeiten, er wurde „weltweit zur Marseillaise der Teenager-Revolution“ (Lillian Roxon). Bis Ende der 60er Jahre wurden davon an die 20 Millionen Single-Scheiben verkauft, bis 2004 waren geschätzte 200 Millionen verschiedener Tonträger mit diesem Song verkauft, kaum ein Musikstück dürfte weiter verbreitet sein, meinen Experten.

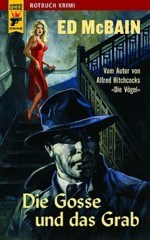

Evan Hunter hieß eigentlich Salvatore Lombino, als Ed McBain ließ er die Polizisten in seinem 87. Revier über viele Jahre in einer zunehmend verrückteren Welt agieren. Sein ganzes produktives Autorenleben lang hatte er stets viele Eisen im Feuer. Keiner seiner Protagonisten aber war so hartgesotten wie Matt Cordell, der Säufer aus der New Yorker Bowery. Die Geschichten waren purstes Hardboiled. Heute noch haben sie eine Toughness, die erschrecken kann – und einen ziemlich heftigen Umgang mit Frauen. Für den im Jahr 1958 erschienenen Roman „I’m Cannon for Hire“ wurde der Name des Detektivs in Curt Cannon geändert. Ein Reprint erschien 2005 bei Hard Case Crime als „The Gutter and the Grave“, McBain hatte kurz vor seinem Tod noch einmal Korrektur gelesen und Publisher’s Weekly fand: „This revised reissue reminds readers that the late McBain had some serious noir chops.“

„I want it fast and hard.“

„I want it fast and hard.“

Joachim Feldmann, dessen Urteil ich sehr schätze, meinte anlässlich der deutschen Ausgabe von „Die Gosse und das Grab“ (Rotbuch 2009): „Genrehistorisch betrachtet ist die Veröffentlichung dieses Romans unbedingt verdienstvoll … als Lesevergnügen allerdings taugt er nur bedingt.“ (Siehe CM vom 28.2.09).

Ich hingegen fand jetzt, nachdem ich mich über Wochen durch die in dieser Artikelserie vorkommenden und nicht vorkommenden Bücher gelesen hatte, die Begegnung mit McBains frühem Roman eine geradezu erfrischende Wohltat. „The Gutter and the Grave“ ist ein Schmuckstück der Hardboiled-Literatur, neben aller existentialistischen Düsternis transportiert es auch die liberale Leichtigkeit und den Geist des jazzigen New Yorks in den mittleren Fünfzigern (von Don Winslow dazu nächstens „Manhattan“). Geschliffen und austariert ist McBains kleiner, schneller, schmutziger Roman ein Stil- und Sittenbild der späten Fünfziger und auch ein Schnellkurs in jenen Geschlechterverhältnissen, deren neue Ambivalenzen nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg manchen Mann verunsicherten und Halt an einer Flasche suchen ließ (siehe die Teile III, IV bis V).

Als Appetitanreger für McBains Gossenroman hier ein Zitat:

She drained her glass and went into the kitchen. When she came back, the bottle was in her hand … „The hell with the police,“ she said. „I’m going to get so drunk I can’t stand. You can stay if you want to see it. If you’d rather nit, then leave.“

She poured three inches of straight bourbon over the ice in der glass. „Here’s to murderers,“ she said, „the goddam world is full of them.“ She knocked off the three inches an refilled the glass.

„Not too fast,“ I said, „or you’ll get sick.“

„I want it fast and hard,“ she said. „I want it to knock me down.“ She drank the refill and poured again, gagging a little as the stuff went down. Then she kicked off her highheeled pumps. Then she out down the bottle und pulled of the half-slip, and then she went to sit by the window in bra and panties, her feet propped up on the window sill.

She killed a third drink and then tossed her long blond hair over her shoulder and shot me a backward glance und flashed the most evil smile since Eve grinned at Adam with the apple in her teeth.

„Come her, Cordell, „she said.

„What for?“

„Come here and kiss me …“

Ein Leben auf der Bowery

„The Gutter and the Grave“ hebt ohne jeden Umschweif an:

„The name is Cordell.

I’m a drunk. I Think we’d better get that straight from the beginning. I drink because I want to drink. Sometimes I’m falling down ossified, and sometimes I’m rosy-glow happy, and sometimes I’m cold-sober – but not very often. I’m usually drunk, and I live where being drunk isn’t a sin, though it’s sometimes a crime when the police go on a purity drive. I live on New York’s Bowery.“

Dort findet ihn Johnny Bridges. Bevor wir erfahren, was die beiden verbindet, erfahren wir, dass Cordell ein Privatdetektiv gewesen ist, dass irgendetwas mit seiner Frau gewesen sein muss und er seine Lizenz verlor.

„What do you want, Johnny“, sagt der Ich-Erzähler Cordell. „I was on my way to getting drunk.“

„I need your help, Matt“, he said.

„My help? How can I help you?“

„You used to be a detective …“

We went to a bar on Fourteenth Street. I didn’t take him to any of the Bowery places, which were a lot less expensive, because I thought they might embarrass him. The bar we went to served both bankers and bums. Johnny ordered a gin and tonic. I ordered rye neat. When the drinks came, I threw mine down and asked for another. I threw that one down too, and Johnny ordered a third for me.

„So what’s the story?“ I said.

Johnny hat eine Reinigung und einen Partner, es gibt Unregelmäßigkeiten, Matt soll sich das anschauen, aber er lehnt ab.

„I’m a bum. Me. Matthew Cordell, bum. I sleep in flophouses or on park benches. I’m drunk twenty-five hours out of twenty-four and I get my whiskey money by panhandling. I’m a bum.“

Am Ende des ersten Kapitels steht Cordell dann doch in der Reinigung – und findet sich am Schauplatz eines Mordes. Die Suche nach dem Mörder wird zu einer kleinen Reise durch die Sozialgeschichte New Yorks, all dies verpackt in einer schnellen, direkten, immer wieder poetisch angereicherten Geschichte. Hier ein Beispiel:

„I’m a slum boy, you see. I was born and raised on the upper East Side of Manhattan before the Puerto Ricans began to infiltrate that part of the city. I was raised among other people who could not speak English too well, and I was part of their slow adjustment to the new world. That section of town was all Irish and Italian at the time. My father was a big mick with a brogue who’d come to America to earn a living … It wasn’t easy to be Irish. It’s never easy being anything that isn’t what everybody else is.

But it wasn’t such a bad place to grow up. The worst neighborhoods never seem so bad or dangerous to the people who live in them …“

Einen Leopardenmantel so tragen, als wäre das Tier noch lebendig …

Dort es ist auch, wo Cordell die Liebe seines Lebens trifft, die ihm immer noch in seinen halluzinatorischen Suffträumen begegnet: Toni McAllister.

„It’s a good name. It still excites me. It excited me the first time I heard it, as if I were waiting to hear that name all my life, and suddenly there it was. And the girl went with it …“ Sie ist blond, hat grüne Augen und ein umwerfendes Lachen, trägt einen Leopardenmantel. „A leopardskin coat, and she wore it as if the animal was still alive, a sleek study in motion, trim and clean, full thighs beneath the woolen dress, slender ankles and the clatter of high-heeled shoes, the subtle swing of leg and tigh and hip … The smell of perfume and class, both delicate scents … a fresh breeze in the garbage-smell of the slums.“

Er verliert sie und sich und seine Zukunft, als er sie – vier Monate erst sind sie ein Paar – mit einem anderen Mann erwischt und diesen zusammenschlägt:

„I had a license for the gun, of course, and I pulled it from the shoulder holster, and I went at him, and I kept hitting him because the son-of-a-bitch hadn’t only taken my wife of four months, he had taken a dream, and dreams are the one thing you should never steal from a man. And so I tried to reconstruct a demolished dream by destroying the demolisher, and all I did was destroy myself.

The police were so kind, the bastards. They understood completely, but they took away my license and my gun and my pride.

End of story. Add a Mexican divorce … I drifted to the bowery. There were a lot of people trying to forget there. Maybe the other guy’s face healed, but I carried scars that would never heal. Alcohol is good for scars; it’s an antiseptic.“

Und dann trifft Cordell wieder auf eine blonde Frau. Auf Christine Archese. Sie ist die Frau des Ermordeten. Das Echo des Kalten Krieges in Gestalt des 1958 noch aktuellen „Frogman Crabb“ (mehr hier), jenes englischen Kampfschwimmers, der bei einer Geheimdienstoperation im Hafens von Portsmouth verloren gegangen war, scheint auf in der Passage, in der Cordell ihr die Nachricht überbringt:

„Your husband is dead. Someone shot him.“

„The reaction is always the same. I would rather swim underwater and attach nuclear weapons to Russian battleships than tell a person a loved one is dead.“

Die Unterscheidung, die Cordell dann anstellt, wir sind auf Seite 44, wird am Ende noch einmal eine wichtige Rolle spielen, hier zeigt sie seinen ehemaligen Professionalismus, der ihn auch jetzt noch über der Wasserlinie hält und ihn zum würdigen Ich-Erzähler einer Hardboiled-Novel macht.

„There is nothing funny about death. It always hits a person right between the eyes, an awesome shock that knocks the breath from the chest and suddenly fills the eyes with agony. Nor is the reaction any different when a person is faking. It is almost impossible to tell fake shock from real shock, and so the reaction to death is always the same.“

Die Schwester der frischgebackenen Witwe kommt dazu, auch sie blond: Laraine Marsh, eine Nachtclubsängerin mit großen Träumen. Schnell geraten Cordell und Laraine aneinander, denn sie bietet dem Macho Paroli:

„I don’t like to be interrupted, Cordell.“

„Get friendly“, I said. „Call me Matt. And go to hell.“

„What?“

„I don’t like women to tell me when to interrupt them.“

„We get along fine, don’t we?“

„Just dandy“, I said. „I want another drink.“

Eine Ode an den Jazz und die Macht der Musik

Die Grenzen des damals Erlaubten strapazierte eine lange, erotisch aufgeladene Verführungsszene (Seite 133–140). Ebenfalls an die Verfassung der Gesellschaft rührte, was McBain im weitgehend rassengetrennten Amerika von 1958 über Musik mitzuteilen wusste. Auf der Lenox Avenue (1987 in Malcolm X Boulevard umbenannt) in Harlem besucht Cordell einen Nachtclub.

„The pad on Lenox was jumping. The musicians ranged from white to tan to brown to black. No one in the room was thinking anything about anything but music. I sometimes think all racial prejudice in the world would evaporate if everyone were taught to play an instrument and then allowed to join a gigantic international band. I’ve never yet met a musician, black or white, who has let color become any sort of barrier. And this holds for musicians who come from neighborhoods where racial prejudice is taught from the cradle. It doesn’t work on musicians. There’s no room for hatred when three men or six men or a dozen men or two dozen men are blowing their different sheets and making a conglomerate sound. The sound is the thing and music has its own color, blue or red or pale yellow or misty pink.

There was harmony in that room, and it didn’t all come from the horns. The harmony was a thing you could feel in the jiggling feet and the clapping hands, the nodding heads, the wide grins when a man played a particularly good riff or rode a solo into the ground. I felt better the minute I walked in …“

Am Ende aber werden Cordells Ermittlungen ihm selbst zum Fluch. Und dann sitzt er wieder auf seiner Parkbank in der Bowery, lässt sich volllaufen:

I drank from my jug. It was very hot, and I felt alone.

I felt very alone.

Ziemliches Trockengebiet: Das 87. Polizeirevier

Ziemliches Trockengebiet: Das 87. Polizeirevier

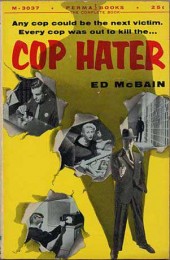

In den 60ern transformierte McBain sein New York, das er liebte und in immer wieder neuen Facetten beschrieb, in die fiktive Stadt Isola, wo die Polizisten von 87. Polizeirevier ermitteln. Seine Idee war es, die Polizeistation in den Mittelpunkt zu stellen und seine Protagonisten als Ensemble zu präsentieren. Otto Penzler: „He’s the guy who defined the police-procedural novel. He didn’t quite invent it, but he certainly made it popular.“ 1956 beginnend mit „Cop Hater“ wurden es über 50 Romane, ein Universum für sich.

Alkohol allerdings spielt in den 87th-Precint-Romanen eine sehr untergeordnete Rolle. In „Heat“ stirbt ein noch als Toter nach Alkohol riechender trunksüchtiger Künstler, der Angst vor Medikamenten hatte, ausgerechnet an Schlaftabletten. In „Killer’s Choice“ wird eine junge Frau in einem Getränkeladen erschossen und liegt in einer Pfütze aus Alkohol und Blut, als die Detektive eintreffen. Carella ermittelt auch mal in einer Bar und gibt jemandem einen aus, um der Erinnerung nachzuhelfen, etwa in „The Heckler“, wo er dabei betont: „We’re not allowed to drink on duty.“

In „Hark“ (2004) verhört Captain John Marshall Frick, der Chef des 87. Polizeireviers, persönlich einen Verdächtigen, sehr zur Belustigung der anderen Polizisten. Freddie ist ein Obdachloser, der sich gerne etwas dudelt, er hat lediglich Geld von einem Unbekannten bekommen, einen Zettel mit einer Botschaft abzuliefern. Der Captain eröffnet das Gespräch mit:

„You bee drinking a little today, Freddie?“

„A little. I drink a little every day.“

Freddie wird bockig und ist ein wenig beleidigt. Unvermittelt sagt er:

„I used to play piano, you know.“

„Is that right?“

„That’s how I startet drinking. There’s always a drink on a piano, did you ever notice? … You play Piano and you drink and you smoke, that’s it. I guess I drank a little too much, huh?“

Schließlich gibt Frick auf und sagt:

„You can go home.“

„Home?“, wundert sich Freddie.

Die Sache mit dem alkoholfreien Bier

Die Sache mit dem alkoholfreien Bier

Am Tatort eines Mordes will im gleichen Buch Detektiv Monoghan seinem Kollegen Monroe erzählen, wie er in einem chinesischen Take-away-Restaurant ein paar Flaschen alkoholfreies Bier kaufen wollte. Monroe findet das so langweilig, dass er sich stattdessen auf Klassifizierungstermini von Brüsten verlegt, weil Monoghan so unvorsichtig war, eine Barkeeperin zu erwähnen:

„I told him I wanted two non-alcoholic beers, and he told me I’d have to get those at the bar. So I go over to the bar, and the bartender – this blonde with nice tits, which was strange for a Chinese joint …“

„Her having nice tits?“

„No, her being blonde … can you please pay attention here?“

„When you say ‚nice tits’, is that what you really mean? ‚Nice tits’?“

„What?“

„Is that a truly accurate description? ‚Nice tits’?“

„Can you please tell me what that has to do with my story?“

„For the sake of accuracy,“ Monroe said, and shrugged.

„Forget it, then,“ Monoghan said.

„Because there’s an escalation of language when a person is discussing breast sizes,“ Monroe said.

„I’m not interested,“ Monoghan said, and looked down again at the breasts of the dead women.

„The smallest breasts,“ Monroe said, undeterred, „are what you’d call ‚cute boobs‘. Then the next large breasts are ‚nice tits‘…“

„I told you I’m not …“

„… and then we get to ‚great jugs‘, and finally we arrive at ‚major hooters‘. That’s the proper escalation. So when you say this blonde bartender had nice tits, do you really mean …?

„I really mean she had ‚nice tits‘, yes, and that has nothing to do with my story.“

„I know. Your story has to do with ordering non-alcoholic beer …“

Es braucht noch eine ganze Weile, ehe Monoghue zu Ende erzählen kann, dass er das alkoholfreie Bier nicht nach Hause nehmen durfte, weil es nur an der Bar verkauft werden kann.

„I did not get it. And it wasn’t beer. It was non-alcoholic beer.“

Fortsetzung folgt: Nächstes Mal Joseph Wambaugh, der über abstinente Cops nur lachen kann, und einige andere Chorknaben.

Alf Mayer

Hier geht es zu Teil I, Teil II, Teil III, Teil IV und Teil V.

McBains Matt Cordell-Geschichten

„Die Hard“ (January 1953, Manhunt)

„Dead Men Don’t Dream“ (March 1953, Manhunt)

„Now Die in It“ (May 1953, Manhunt)

„Good and Dead“ (July 1953, Manhunt; as Ed McBain)

„The Death of Me“ (September 1953, Manhunt; as Ed McBain)

„Deadlier Than the Male“ (February 1954, Manhunt)

„Return“ (July 1954, Manhunt)

„The Beatings“ (October 1954, Manhunt)

„I Like ‚em Tough“ (1958; versammelt die ersten sechs Stories)

„I’m Cannon -For Hire“ (1958; 2005 als „The Gutter and the Grave“)Ed McBain: Die Gosse und das Grab (I’m Cannon – for Hire, 1958 aka: Curt Cannon; als The Gutter and the Grave, 2005 bei Hard Case Crime). Roman. Aus dem Amerikanischen und mit einem Nachwort von Andreas C. Knigge. Berlin: Rotbuch (Hard Case Crime) 2009. 220 Seiten. 9,90 Euro. Foto McBain: James M. Curran, Wikimedia Commons, Quelle.